Editor’s Note: As part of its 50th anniversary celebration, the Homer News has asked former “Newsies” to reminisce about their time at the newspaper and some of the top stories of the day.

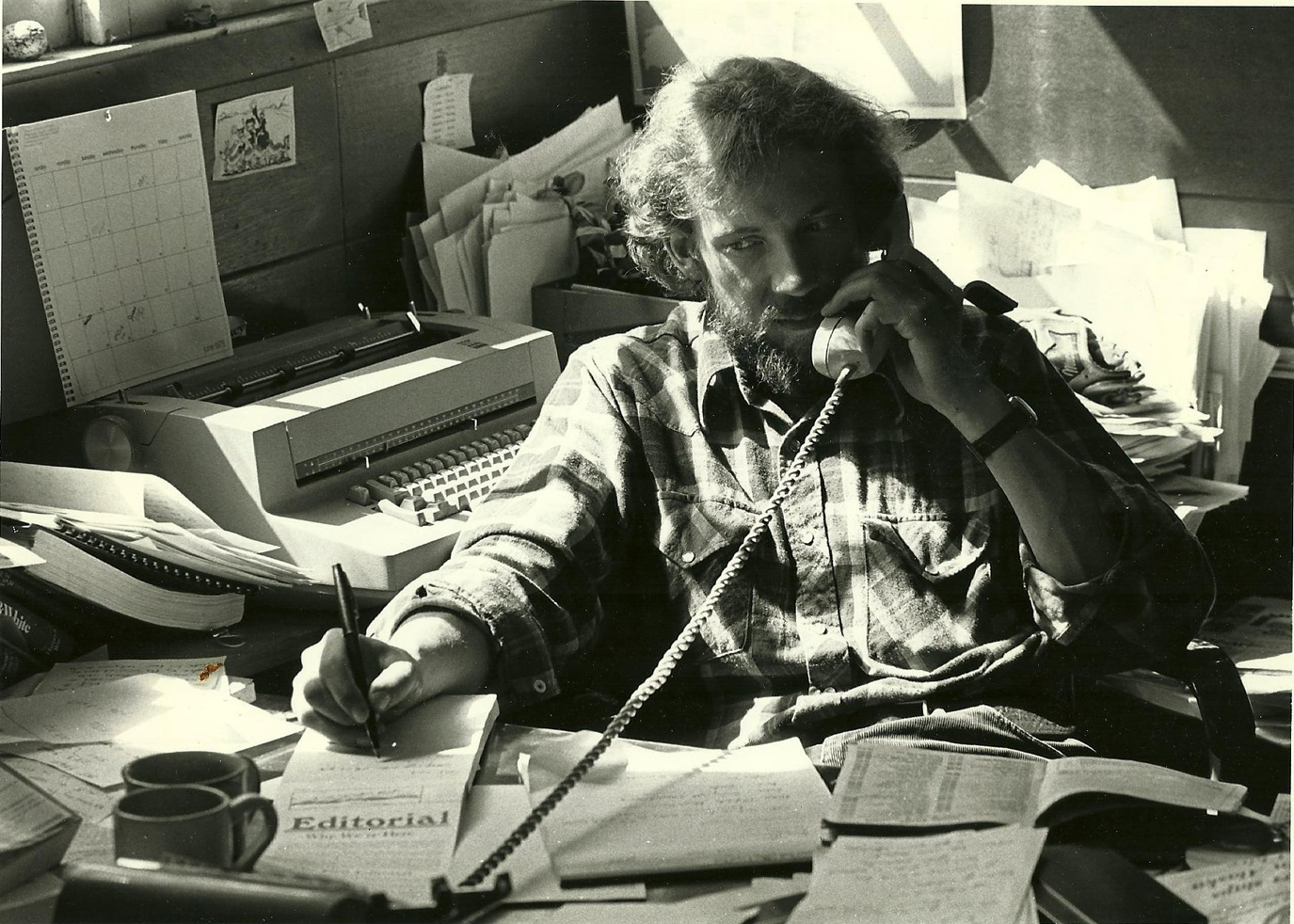

In the second such piece, Tom Kizzia, former managing editor, talks about his time at the Homer News in three separate stints — from 1975-76, 1977-78 and again briefly in 1989.

Paving trucks were sealing off the mud east of town on the day I showed up in September 1975. Change was arriving in Homer, and one of the next things to change that fall would be the Homer Weekly News.

I came to town for a short visit with friends from back East. I had just graduated from college, and after a summer’s adventures I was staying in Alaska to find a newspaper job. I had interviewed at the Anchorage and Fairbanks dailies and now had to wait, doubting my few college clips had impressed anyone in those tough pipeline-building towns.

In Homer, though, I learned someone with my impressive journalistic experience was very much in demand. No one had a news background at the local weekly paper, where my college friends, Ken Castner and Nancy Lord, were helping out — though Nancy had recently been benched for publishing an opinion piece saying she preferred the dusty old Pioneer Avenue.

Homer was different then. Oldtimers were uneasy about the newcomers and the hippies. No eager welcome sign greeted travelers at the dirt pullout on top of Baycrest Hill. Only one sportfishing charter captain plied the bay, and he had a hard time finding anyone who would pay money to fish. There were no First Friday gallery tours or savory lunch spots, no tourist boardwalks on the Homer Spit. There was, however, local king crab at the Porpoise Room and, this side of the canneries, maple bars at Dean’s Doughnuts. And mountains to make you fall on your knees.

By the time the pavers had proceeded far out East Road, I was the newspaper’s first fulltime editor/writer. The owner, Gary Williams, said he would pay me $600 a month to write the news. Gary would sell the ads. We shook hands in the glow of the meat and dairy cooler in Inglima’s Market.

The News was produced in a shed alongside a downtown machine shop (today, the Fireweed Gallery). Within weeks, we had moved along Pioneer Avenue to a roomier quonset-roofed structure, now gone, next to a law office (today, Cafe Cups) and across the street from the post office (today, Don Jose’s). Brother Asaiah dropped by the new digs to welcome me to town, saying he felt good vibrations coming from my desk. And it was there that Don and Arlene Ronda burst through the door, six months later, to ask if the rumors were true that Gary had fired me in response to threats of an advertising boycott.

Homer readers knew by then that their new managing editor looked askance at some customary local practices — such as the half-off health-care discounts going to the appointed hospital advisory board, or the cozy post-meeting city council gatherings over drinks at the Waterfront (today AJ’s), where a sign proclaimed “What Foods These Morsels Be.”

But when it came to the big stakes of a hoped-for oil boom, the paper’s skeptical attitude was harder for some oldtimers to abide.

A jack-up drilling rig, the George Ferris, was standing inside the Spit, unable to start work in Kachemak Bay because of a state Supreme Court lawsuit brought by local commercial fishermen. City council meetings grew lively, as stultifying discussions of reinvented wheels and carts put before horses turned to debates over oil support activities. Big changes were afoot at the Chamber of Commerce lunches, where new members, king crab boat owners whose pot buoy lines had been severed by seismic exploration vessels, showed up to glare at the pro-oil officers. The business establishment didn’t appreciate the “town divided” drumbeat in the Homer News. It was time to rein the paper in.

Honestly? The managing editor probably could have used a little reining in. Though he tried to be straight and even-handed in his day job, he filled his spiral-bound journals at night with self-righteous spume about the shortcomings of 1970s small-town America, his conscience supercharged by Vietnam and Watergate, his mind humming with Sinclair Lewis and H.L. Mencken and Noam Chomsky. Subdividers and freight handlers he judged the most shameless at equating public good and private self-interest; king crabbers, doing likewise, were excused as hunter-gatherers on the side of Nature. At the same time, however, the new editor seemed overly impressed by the folk wisdom he heard around the coffee table at the Sterling Cafe, and in awe of his neighbors’ ingenuity and energy, their ability to survive the dark winters and to yank his little sedan out of ditches.

At the office, Gary Williams and I regarded one another with a mix of affection and exasperation. I fought to keep the news columns forthright and open to dissenting views. Gary wrested back control of writing the editorials, waffling and searching for consensus. He had grown up in Anchor Point but went to college in Oregon, where he expanded his mind through the study of city planning as well as other means. He understood that local government could be a positive force for community development. But such a neo-hippie idea faced heavy political if not Freudian obstacles in Homer, where every word in the paper passed beneath the eye of Gary’s conservative, church-going, business-owning parents. A typical Tuesday night scene: Gary reading my stories for the first time as he pastes them up, whining “You’re killing me, man,” then laying out a provocative headline with a big smile.

Finally the dam broke. In March, 1976, Gov. Jay Hammond sent his firebrand, fiddle-playing attorney general, Avrum Gross, to find out if Homer would support a law revoking the oil leases in the bay. I suggested to Gary he host a dinner before the big meeting, inviting a few leaders from both sides. When she learned of this, the mayor, Hazel Heath, was livid. She had planned to take care of the distinguished visitor, just her and a few associates. That was the way business had always been done. She had been outflanked.

That night, when the townsfolk crowded into the high school gym (today, the middle school), Gross steered the lively conversation to a final straw poll on the general idea of buying back the state oil leases. The only ones standing in opposition were the chamber and city officials accustomed to saying Homer couldn’t stand in the way of progress. The final vote was three-hundred-something to 18.

I wrote the banner story that week with a note of glee. The rumors of my firing followed soon after. But Gary brushed off the critics. He even agreed to let me take a boat out to inspect the “best available technology” on the George Ferris.

The rig’s aptly named superintendent, Ralph Oxenrider, showed me the rig’s four legs, each one weighing 600 tons. That week I wrote: “The Ferris’s legs are currently lowered 130 feet, and (according to the fathometer) only 50 feet of that is water. Oxenrider says he expects no problem when it comes time to jack the legs up out of the soft muck of Mud Bay.”

There is no space here to tell the story of the spectacularly timed demise of the George Ferris, whose legs can still be found in the soft muck of Mud Bay. But the profound changes experienced by Homer as a result of that first oil spill went beyond the eventual oil-lease buyback and the shift to a future focused on fishing and tourism rather than heavy industry. The town’s way of deciding things opened up. The newspaper had helped.

The change was apparent that fall when Gary Williams ran against Hazel Heath for mayor. On the city council, Nelda Calhoun was indignant. She said it was a conflict of interest to be both publisher and mayor. I agreed, though I think for opposite reasons. How was the mayor going to feather his own nest — veto an ordinance to create more news and sell more papers? The problems I foresaw all came the other way, piled on the reporter whose boss was also mayor.

Gary won the 1976 election, despite a splintering third candidacy of barroom troubador Hobo Jim, who drew off some of the long-haired vote. Soon after, I left the paper to build a cabin in the woods.

Chapter Two

I ran out of money and went back to work for Gary in October 1977. The Homer News had continued to prosper and grow, and soon he put the paper up for sale.

No local person made a serious offer that winter, but several outsiders did. I argued unabashedly for the flattering pair of Pulitzer Prize winning editors — Tom Gibboney, who won the prize at the Anchorage Daily News for investigating the Teamsters Union, and Howard Simons, who won at the Washington Post for investigating Watergate. Gary agreed, and soon Gib moved down from Anchorage to take the publisher’s desk in the office (today, Cafe Cups).

Our famous new owner came to visit Homer the next summer. Howard Simons told us he appreciated the “grace notes” he spotted in our stories — the unexpected details and passing turns of phrase that brought a little smile and invited readers to go deep in stories. He was glad to see we were so committed to the community. But he wouldn’t offer big advice. “I wouldn’t want you to come to my town and tell me how to run my newspaper,” he said.

That summer I turned the managing editor’s job over to Chip Brown, a poet friend who had joined our college crowd in Homer. Chip, an exceptionally gifted writer, soon made the unheard-of career leap from the Homer News to success at the Washington Post.

Gib asked if we could recommend a replacement. Chip and I mentioned Joe Wills, another friend from our campus newspaper. We were kidding, But it wasn’t long before Homer readers were subjected to their third consecutive English major from Hampshire College.

Epilogue

In February, 1989, I came back to the Homer News for what I thought would be a few quiet months filling in for my friend, Joel Gay. He had a fellowship that would take him to Japan. Tom Gibboney, his boss, also was away, on a one-year fellowship at Stanford University. I had left my Anchorage Daily News job and written a book and wasn’t sure which way to go next. It sounded like fun. Another short visit.

I wasn’t back long before I realized the Homer News faced a crisis. Joel announced he planned to take a job on a seiner when he returned. Gib was furious that Joel wasn’t coming back, because Gib didn’t plan to come back, either. The News had three reporters, but the two veterans, underpaid and exhausted, seemed headed for the exit, while the cub reporter told me she preferred to guess at facts rather than admit when she didn’t know something.

I wrote a letter of alarm to Howard Simons. He had left the Washington Post to lead Harvard’s prestigious Nieman Program for journalism but retained a soft spot for his little newspaper in Alaska.

Then I turned to the impending 25th anniversary of the city of Homer. I worked long hours to produce a special edition on March 30, 1989, featuring an affectionate portrait of the community’s many feuds back in 1964. Having helped usher in the new, more worldly age of Homer, I was filled now with fond nostalgia for what had gone before. At a Pratt Museum reception, Hazel Heath clutched my sleeve and said it was the best issue of the Homer News we’d ever produced.

Few others noticed, however. On page three of that same edition was a small headline: “Current carrying oil this way.”

Within days, the Exxon Valdez oil spill pandemonium hit Homer.

Improbably, it would become one of the Homer News’ finest hours. Our small staff rose up in defense of the town. Worries about the future were shoved aside. In that time of heartache and futility, journalists were among the few able to put their adrenaline to good use.

Then in May I got a phone call at the office that put the paper’s troubled prospects in deeper perspective.

Howard Simons was on the line with news that wasn’t public yet. He had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He’d been given two months to live. He thanked me for my long letter and was confident we’d sort things out because he knew we loved Homer. Meanwhile he’d gone out and enjoyed his first hamburger and milkshake in years.

That same week I got a call from my former editor in Anchorage. He asked if I wanted to come back to the Anchorage Daily News and be based on the Kenai Peninsula. My new bride, Sally, said she was ready to move into the cabin in the woods.

So we came back to Homer to stay.

Talented journalists showed up after all and helped the Homer News to thrive. Then in 2000, the paper’s owners, including Howard Simons’ family, sold the paper to Morris Communications.

And the rest is history — somebody else’s history.

Tom Kizzia was a longtime reporter for the Anchorage Daily News, based for much of his career in Homer. He has written two non-fiction books: “Pilgrim’s Wilderness” (2013), a national bestseller, and “The Wake of the Unseen Object.” Last month the Homer Council on the Arts named him Homer’s Artist of the Year.

Used with permission © Tom Kizzia, 2014