By Clark Fair

AUTHOR’S NOTE: William Dempsey killed two Alaskans in 1919, was sent to prison in 1920 for his crimes, and escaped from prison in 1940. The first eight parts of this story introduced Dempsey’s victims and the judge who presided at his trials. Dempsey spent more than a decade attempting to persuade that judge, via letters from prison, to recommend him for executive clemency.

Final Moves

William Dempsey first became eligible for parole on July 9, 1935. Former Judge Charles E. Bunnell, who had tried Dempsey on counts of first-degree murder in Alaska and who had sentenced him to death after his two convictions, was asked to comment on the pardon possibility. The views of other court officials were also requested.

Bunnell had no desire to spend the rest of his life looking over his shoulder for an angry ex-inmate. He recommended rejecting the parole application, claiming Dempsey would be “a menace to society” if set free. He also worried that Dempsey might use freedom to travel north to Alaska and exact his vengeance on every court official he believed had wronged him — just as he said he wanted to do after his sentencing back in 1919.

The parole board denied Dempsey’s application on July 5, 1936. His case for parole was reopened in May 1937 and again denied.

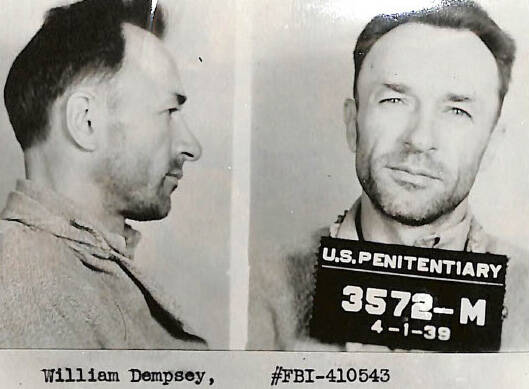

Then, in February 1939 a Leavenworth prison committee, tasked with alleviating overcrowding in the facility, recommended that Dempsey be transferred back to the McNeil Island federal penitentiary. The transfer took place on April Fool’s Day.

His outgoing paperwork included this comment on Dempsey’s neuropsychiatric state: “History would indicate that this young man in his youth was impulsive, unsettled, unstable emotionally and that his instinctive drives were not under control…. Since his long sentence here he is more mature and settled in his habits.

“He has made an excellent adjustment here (and) does not show any antipathy towards society or his environment. It is believed he can continue to adjust to prison routine and his transfer to McNeil would in no way upset his adjustment.”

On Jan. 30, 1940, nearly eight months later, Dempsey, while on a road gang in a heavy fog, slipped away from the work detail. His absence was not noticed for two to three hours. McNeil authorities never saw him again.

Final Mystery

In 1919, according to a summary penned by the prosecuting attorney in William Dempsey’s trials, an Anchorage witness had claimed that Dempsey’s motivation in killing Marie Lavor was a desire for more money and an interest in going to Mexico.

In March 1935, a special report from Leavenworth prison noted that Inmate Dempsey had an IQ score of only 83, placing him in the 39th percentile. However, stated the report, he was nevertheless interested in self-improvement: “This man has spent (about two years) in work and study in the prison laboratory … (and) has done rather extensive study in Spanish.”

After Dempsey’s escape from McNeil in 1940, officials postulated whether he had been capable of swimming the 800-yard span between the island and the closest mainland in frigid Puget Sound waters. If he had survived the crossing, officials wondered, where would he have gone? To Alaska to exact his promised revenge? To what was left of his family in Cleveland? To one of his groupies in Southern California? To Mexico?

Most assumed that Dempsey had not survived the swim. Charles Bunnell was not so sure. On Feb.1, only two days after the escape, Bunnell wrote a letter of concern to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

Hoover wrote back and tried to assuage Bunnell’s concerns.

The day after Bunnell wrote to Hoover, an Olympia, Wash., newspaper reported that a woman living in the Gig Harbor area, north-northeast of McNeil Island, claimed that a man fitting Dempsey’s description had appeared at her farmhouse and obtained a meal from her. A Seattle paper said that the woman later “identified a photograph of the convict (Dempsey) as that of a man who stopped at her home … and begged for food.”

Farther north the following day, a Bremerton, Wash., newspaper published a story about a local clergyman who claimed that a man — whom he identified later through police photographs as William Dempsey — had stopped by his residence and begged for money and a warm jacket. The man, who claimed he was a commercial fisherman, was covered by a long brown slicker and a white rain hat of the type worn by fishermen.

The man told the minister that he had just been discharged by the owner of a fishing boat, that he had walked a considerable distance, and that he really needed a place to rest. The clergyman gave the man a single dollar and sent him on his way. He told his visitor that he had no resting place or coat to offer.

No other “confirmed” sightings of Dempsey, or his look-alike, ever materialized.

Final Words

On Feb. 8, a nervous Charles Bunnell was contacted by Robert Bates, a freelance writer for a true-crime magazine, and asked for his version of the William Dempsey story. Bunnell politely declined, telling Bates that he believed a story at that time was “premature.”

No record exists of Dempsey contacting Bunnell after his prison escape. Bunnell retired from the University of Alaska on July 1, 1949, and eventually retired to California, where he died of a heart attack on Nov. 1, 1956.

The March 1950 issue of Master Detective magazine featured Dempsey in a one-page section called “Master Detective Line-up: Watch for These Fugitives.” Under a generally correct bio of Dempsey was this advice: “If located, notify Director J. Edgar Hoover, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Washington, D.C.”

In October 1954, True Detective magazine published a similar “Rewards” section, using nearly identical language.

But the most impactful publication of Dempsey-related material appeared in Master Detective in October 1953. Entitled “Blonde in the Wilderness” and penned by R.J. Gerrard, the multi-page narrative invented dialogue and minor characters to move the story along. It altered facts to sensationalize action. It offered artwork and details designed to titillate more than inform. It transformed Dempsey into a cunning bootlegger, Lavor into a young and voluptuous hooker with a head for business, and so forth.

And it succeeded, unfortunately, in becoming the go-to version of events for a number of future writers and researchers for whom the story of William Dempsey, Marie Lavor, U.S. Deputy Marshal Isaac Evans and Charles Bunnell was decades in the rearview mirror.

When William R. Cashen wrote his 1972 biography of Charles Bunnell, Chapter 5 (“The Dempsey Case”) drew heavily from Gerrard, particularly concerning Lavor and the personal history of Dempsey. Likewise, when Alaska historian Claus-M Naske, in 1986, wrote a long, insightful piece about Dempsey and Bunnell for the Heartland magazine section of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, he relied on Cashen when his own research failed to unearth more factual information.

Both Cashen and Naske were careful reporters, but they doubtlessly lacked access to all the material now available, albeit still not fully consolidated.

Even a full trial transcript and a copy of all court documents and prison records might never completely reveal the truth behind the lies and obfuscations of a man who took two lives and disturbed many more.