Megan Wiard returned to Homer in March to apologize. The last time she was in her hometown, about six years ago, Megan was an addict.

“I made amends to the people I stole money from. I made amends to the police station and causing harm in their town, selling drugs in their town. I made peace with the town,” Megan said. “I thought it was going to be a lot more difficult. My boyfriend came with me to support me and my family supported me. I’m grateful I got to do it.”

Megan began drinking and smoking pot in high school, and then became addicted to harder drugs after graduation.

“I think I was bored and I think it’s something we’re born with,” Megan said. “I always had this emptiness in me and it came out in insecurity and eating disorders and using is the way I started to fill that void.”

For a long time, her parents, Annie and Rob Wiard, were unaware of Megan’s problem. However, even before Megan’s parents knew she was addicted to drugs, they knew their daughter was struggling.

A family in Homer

Annie and Rob Wiard moved to Homer from New Mexico in 1984 with their two daughters so Rob could get into commercial fishing. They enrolled both Megan and her older sister into private school, and then public school when Megan was in fifth grade.

Once in public school, Megan was bullied through middle school.

“I started getting sick a lot — getting migraines and stomach ulcers — because I had a lot of anxiety,” Megan said. “I remember my mom tried to make it better. She would take me up to Anchorage to buy me new clothes.”

Annie tried to help increase Megan’s happiness, but in high school Megan still felt out of place. Her friends were smoking pot and drinking, so she did too. For the first time, she felt like she fit in. Megan soon noticed that her drinking habits were different than her peers’.

“I started drinking and I felt normal,” Megan said. “I would drink to get messed up. I wouldn’t have a few beers or shots and have fun; I would have the whole bottle to myself.”

Megan decided to leave Homer for a foreign exchange program in Costa Rica when she was 16, thinking that getting away from her friends would curb her partying. Though she spent six months there, Megan left the program and partied throughout Costa Rica instead, getting deeper into the bulimia she also already struggled with. After returning to Homer, Megan and her parents decided she should go for treatment in Arizona for her eating disorder.

The 60-day treatment program cost about $50,000, Annie said.

“(Megan) was there for two months, she probably needed more time but it’s extremely expensive. We refinanced the house to get her there.”

Upon returning for treatment, Megan “decided to live like a normal person,” like she saw her sister doing, she said. She graduated high school and stayed in Homer, but as time passed, Annie and Rob Wiard watched Megan grow more chaotic, though they were unsure what they were seeing symptoms of.

“I was dating someone, we got our own place. All of a sudden I got obsessed with losing weight. I got bored with my boyfriend; we fought a lot,” Megan said. “One day I decided to go to the Memorial Day weekend party at Anchor Point and I went out with one of my friends. They had started using pills and cocaine. I decided I was going to do this.”

Instant addiction

From Memorial Day in 2009, Megan couldn’t stop using. All of her money went to pills and cocaine, she said. When she couldn’t sleep, she took Xanax. One night when they were both high on Xanax, her boyfriend drove her car off West Hill, flipping it over.

“That’s when I realized consequences wouldn’t stop me from using,” Megan said.

While cocaine and Xanax were fun, she said, oxycodone became her drug of choice after she was introduced to smoking it.

“I thought this is it. This is what I’ve been missing all my life,” Megan said. “I convinced myself I wasn’t a real drug addict unless I was using meth.”

Though her parents were helping her financially while Megan worked to support her and a new boyfriend’s habit, they were unaware of the extent of the problem. Megan stayed guarded and kept them out, Annie said. For a while, the only clue was increasing isolation they felt. Parents of Megan’s friends fell away from contact with the Wiards, blaming them for Megan’s behavior, Annie said.

“We were pretty clueless because she was good at keeping things from us,” Annie said. “We could just see she was really unhappy and having a hard time, but we tried to be there for her. We tried to be accessible. We tried to talk to her.”

“I do remember one winter, she changed a lot. I remember she was at our house one night and she said, “You don’t know what I’ve done.” … It just felt ominous at that time,” Annie said. “(That spring), I really saw a big change in Megan. I think the thing that affected me the most at that time was she has these beautiful green eyes … and her eyes started turning black. It’s hard to explain, but when you look into an addict’s eyes, they’re dead, because they’re dying inside in every way.”

A mother’s helplessness leads to enabling

As Megan floundered, so did Annie. The guilt over her daughter’s struggles weighed on Annie, and she felt that Megan’s decline was somehow her fault. To compensate, she tried to help Megan anyway she could: picking her up from hotels in Homer, driving her to work, or to meet people she didn’t know. Enabling Megan became an addiction for Annie as she hoped helping her daughter out financially and practically would change something.

“When you’re looking from the outside it makes no sense why you would do this, but when you’re in it, it’s just, ‘What am I going to do to help my daughter through the day?’” Annie said. “She needs a ride. She needs money. I need to pick her up and take her over to those weird guys over there who give me the weebie-jeebies … Nothing else mattered but saving her.”

A trip to visit their older daughter, who was studying abroad in Italy, pulled Annie and Rob out of the private “world of insanity” in which they lived in Homer. After they returned, they decided they could not keep enabling Megan in her addiction. At the same time, Megan came to them and confessed her trouble with drugs. She was scared after getting “dope sick,’”or experiencing withdrawal symptoms, for the first time from the oxycodone.

Rehabilitation

Through a family member’s recommendation, Annie and Rob secured a spot for Megan in Austin Recovery in Texas. The center recommended that Megan not go through withdrawals on the plane, so they gave her enough money to buy drugs before she left. Megan got on the plane high, but made it all the way to Austin and checked into the residential program.

Recovery options in Alaska are limited due to space and number of recovery centers. Waiting lists can often be a barrier to recovery for addicts who want to receive treatment.

“Usually when they say they’re ready you have 24 hours,” Annie said of addicts. “Otherwise they start going off again.”

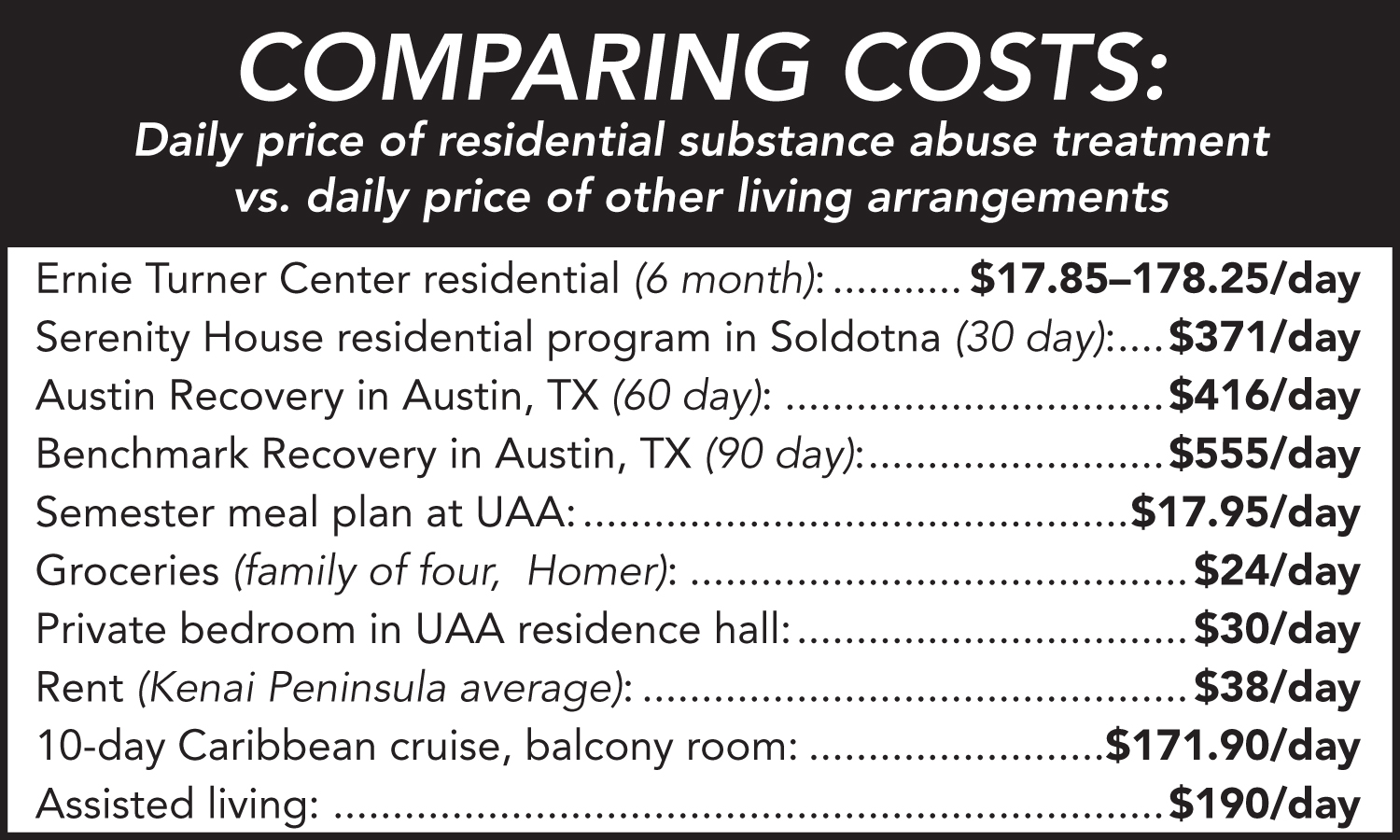

Serenity House, the only residential substance abuse program on the Kenai Peninsula, currently has 12 beds for its 30-day program. A 30-day stay at Serenity House costs $11,130.

Ernie Turner Center in Anchorage has a six-month residential program, also with a waiting list. The cost is adjusted by income and ranges from $17.85 to $178.25 per day, which comes out to approximately $3,266 to $32,619 for an entire stay.

Megan spent 60 days in Austin Recovery, which cost about $25,000. Though they felt Megan needed more time, Annie and Rob were tapped out of funds. After a time in sober living, Megan relapsed, unknown to her parents, and began manipulating them from afar.

“I thought I was well, I didn’t understand the severity of addiction. I was feeling better and gained a little weight. I did okay for a little bit and then that restlessness set in,” Megan said. “I wasn’t really doing a program, I would go to meetings but I wouldn’t really do the work.”

Relapse: addicted and homeless

Megan convinced Annie to help her boyfriend from Homer come out to Austin. Since a newer version of oxycodone prevented smoking, they switched to heroin.

“As much as I loved oxy, I loved heroin more,” Megan said. “My parents thought I was sober. I was just getting high and they were paying for all my things. I told them I had to do an internship (at the recovery center) so I couldn’t work. I really believe addicts are the smartest people in the world because we will say the craziest things to get drugs and do the craziest things and we usually succeed.”

Megan’s parents figured out that their daughter had relapsed and stopped helping her financially. Megan went in and out of jail for possession or selling drugs several times, moved from relationship to relationship, worked at a strip club to support her habit, and started smoking crack as well. Eventually, she tired of heroin and tried meth.

“Someone would come over and I’d say ‘Sure, I’ll try anything,’” Megan said. “Drugs weren’t working for me anymore.”

Megan ended up living on the streets, sleeping anywhere she could. She supported her habit by stealing and sleeping with people for drugs. Her boyfriend was abusive, and Megan received a lot of trauma from him and other people on the street, she said.

“This self hatred I had was so intense that I couldn’t stop,” Megan said.

Megan ended up living with another boyfriend who lived in a nice house and owned a Lexus. She got his car stolen, and broke all the windows in his house because of meth psychosis, she said. After she was arrested with meth, his father bailed Megan out and gave her the choice to go to treatment or back to jail. Megan refused treatment and ended back in jail after her boyfriend’s father pulled her bond. For awhile, she thought going to prison would be the best option because she figured she could still get high. After 30 days in jail, Megan considered treatment.

“Out of the blue, she called from jail,” Annie said.

“It was possession and it was her third one and she was looking at years,” Rob said. “For us, personally it was a relief. The phone wasn’t going to be the coroner. It wasn’t going to be somebody calling because she was dead or her calling because she needed money. It gets to where you hated hearing from your daughter because you knew it was bulls–t.”

The final chance

Annie and Rob were skeptical about Megan’s desire to go to treatment and hired interventionist Lori Leonard of Hope Interventions at the recommendation of Austin Recovery. Leonard and a legal interventionist visited Megan in jail and told Annie and Rob that Megan was serious this time. Through Leonard, the Wiards were able to send Megan to Benchmark Recovery, now known as BRC, in Austin at a discounted rate.

“We borrowed money from my sister; actually my sister gave us money to do that. We refinanced our house and Megan was scholarship-ed in and they discounted it for us, and it still cost $11,000 a month,” Annie said. “If you don’t have money, you don’t get to go. And it’s better with insurance now but insurance will do 10 days and think that’s enough. I mean it’s ludicrous. It took Megan four months so she could get up in the morning and make her bed.”

Benchmark’s peer counseling-based program helped Megan fully separate herself from her addiction. The counselors at Benchmark are often former addicts, who can relate the patients’ experiences. They also encourage reliance on a group of peers for support, Megan said.

“They told me the truth even when I didn’t want to hear it. All the delusions I’d be living in. I was forced to grow and change and get sober and get my life back,” Megan said. “My parents came to see me and that was the happiest time I’d had in years. I just remember we were all crying and I was sober. They hadn’t seen me in years. That was the most amazing time and at that point it was definitely worth getting sober.”

Megan spent 90 days in the residential program, and then spent another year with Benchmark’s recovery coach program and in sober. In total, Benchmark’s programs cost the Wiards approximately $52,600. Over the course of nearly 10 years, Rob estimates that they spent about $200,000 on rehabilitation programs.

Success in action

However, Benchmark was the last program that Megan went through. Now 27 and two and a half years sober, Megan works at BRC and helps women go on the same journey to recovery.

“I’ve come so far. I still work at that treatment center and I get to watch women go through that program. I have my own place. I have a healthy relationship, I have my family back,” Megan said. “There are times where I get fearful and I move through it. I have a community of women who are there supporting me if things come up.”

After years of silence, Annie and Rob are also ready to talk about their struggle as they watched their daughter go through addiction.

“Recovery or help for the parents is hard because there’s shame associated with it, but we don’t really feel shame or embarrassment about that anymore,” Rob said. “We did for a long time.”

As heroin and other drug use increases in Homer, Annie and Rob hope that the community’s open approach to dealing with addiction also continues. Stigma only creates more isolation and shame, Annie said. Talking about the issue is a better way to battle it.

“When I made amends to the police station, the officer said heroin is a big problem here now,” Megan said. “I highly encourage people to talk about it.”

Anna Frost can be reached at anna.frost@homernews.com.

Support options for family members of addicts:

AlAnon Family Group at Homer United Methodist Church:

Tuesdays, noon to 1 p.m.

Thursdays, 6:15-7:15 p.m.

The Addict’s Mom: addictsmom.com

A free online support group connecting mothers of addicts with the purpose of sharing without shame.