Editor’s note: The emails referred to in this story are available at this link. To prevent spamming, the email addresses have been removed:

http://static.peninsulaclarion.com/work/emails/threads.html

Organizers of a recall effort targeting Homer City Council members Donna Aderhold, David Lewis and Catriona Reynolds say emails showing the evolution of the failed so-called “inclusivity” resolution indicate why a recall is necessary.

A Homer News analysis of the emails reveals the original proposal was an anti-Trump and a sanctuary city resolution, but it also shows the complicated, messy process of crafting resolutions and ordinances.

Recall co-sponsor Larry Zuccaro wrote in a letter to the Homer News that Homer citizens should submit a public records request for emails on the resolution.

“This is where the truth will be found for all to see,” Zuccaro wrote. “I think once everyone sees (this) email correspondence, it will be clear to all that nothing short of a recall process would be acceptable.”

The Homer News asked petition leader Michael Fell why he thought the emails were damning, but he declined specific comment on that question.

“We don’t wish anyone any harm,” Fell said. “We want the citizens of Homer to make their own decisions based on what they’ve seen in the emails.”

Aderhold said a lot of the anger against the “inclusivity” resolution which was presented to the council and its evolution stems from confusion about how city government works.

“I think there’s a lot of misinformation out there, and misunderstanding of what a resolution is, and what a resolution does, and what the actual process is,” she said.

Last Thursday and then on Monday, the Homer News filed with the city and was granted two records requests for city emails related to Resolution 17-19, the “inclusivity” resolution, for emails Jan. 1-Feb. 18 and a follow up for emails from Jan. 1-March 15, 2017. This reporter looked through all 541 of the emails.

About 90 of the emails show correspondence between Aderhold, Lewis and Reynolds regarding preparation of the final version of the “inclusivity” resolution, but also include discussion by other council members and Mayor Bryan Zak. Many of the emails were routine responses by City Clerk Jo Johnson to emails submitted by citizens or to council members on introducing agenda items. Other emails came from citizens opposing or supporting the resolution.

The Homer News analysis and reading of the emails show this:

• The preparation of the “inclusivity” resolution included at least three versions, a draft originally written by citizen activist Hal Spence that included whereas clauses critical of President Donald Trump, a draft sanctuary city resolution written by Reynolds, and a revision of the anti-Trump version by Aderhold and Reynolds submitted to the council as the final resolution.

• With Aderhold, Lewis and Reynolds as sponsors, the anti-Trump version was initially submitted to the city clerk to be included on the Feb. 27 agenda. Before the 11 a.m. Feb. 22 deadline for publishing the final agenda, Aderhold and Reynolds revised it, removing any references to Trump.

• Using their city of Homer email addresses, Aderhold, Lewis and Reynolds discussed various versions of the “inclusivity” resolutions, sometimes between two of them, but not among more than the three of them. Under Alaska’s Open Meetings Act, four or more council members cannot interact unless it’s in a publicly noticed meeting. That includes “meetings” conducted by email.

• The list of emails includes emails sent to private email accounts that council members forwarded to their city email accounts.

• While not participating in writing the “inclusivity” resolution, other council members and Mayor Bryan Zak expressed concerns.

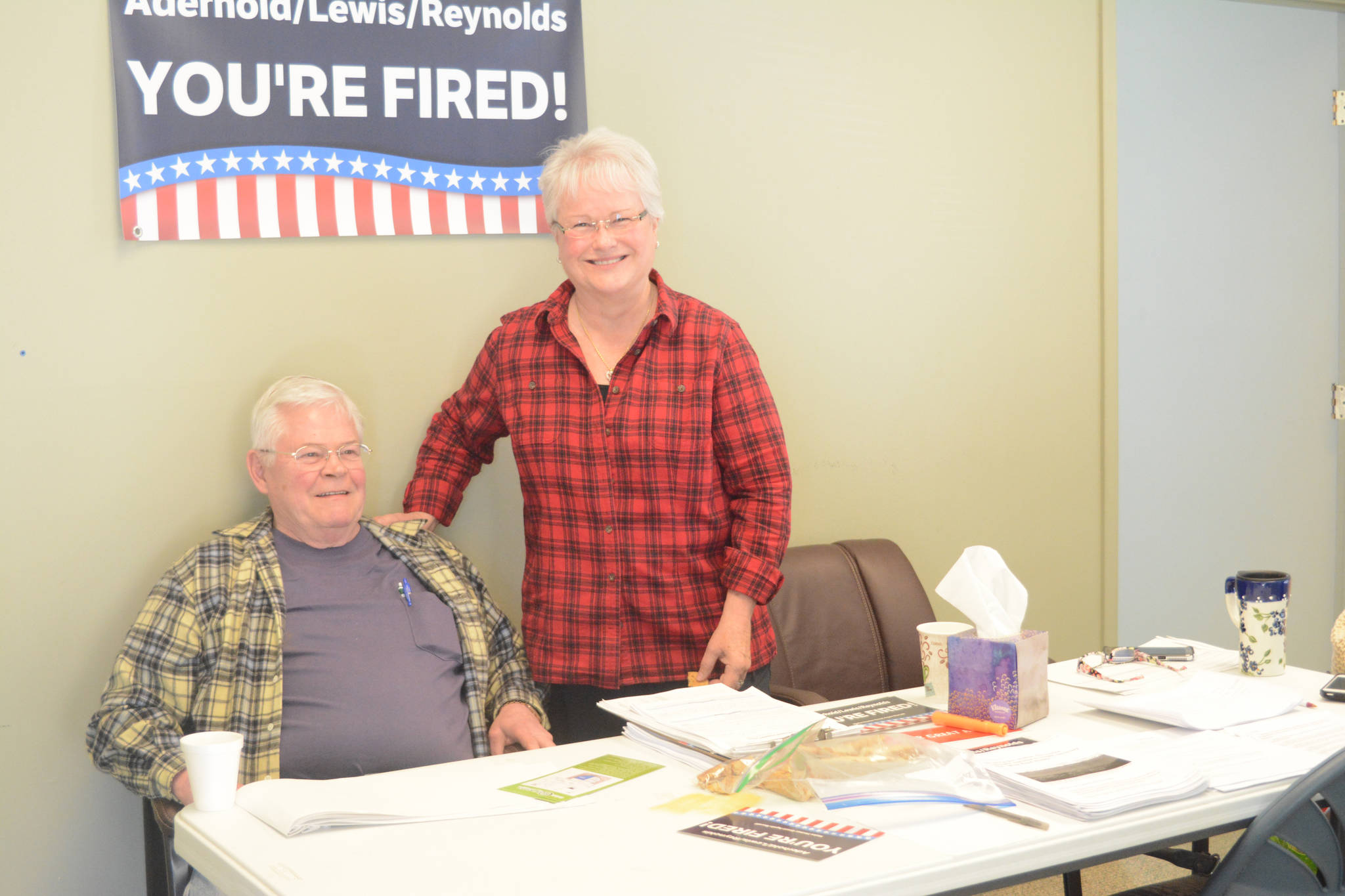

Last week, the recall group got approval by the city clerk to begin gathering signatures to recall Aderhold, Lewis and Reynolds. As of Monday, petition sponsor Coletta Walker said they had gathered more than 300 signatures, close to the 373 registered voters required to force a recall election. The recall group has an office on Ocean Drive where they collect signatures and provide information on the recall. A sign out front says “You’re fired” and another says “Make Homer great again.”

In their application, the group alleges that “Aderhold, Lewis and Reynolds are each proven unfit for office, as evident by their individual efforts in preparation of Resolution 16-121 and 17-109, the text of which stands in clear and obvious violation of Homer City Code Title 1.” Title 1 prohibits political activity by city officials while on duty, defined as support for a political candidate or ballot proposition.

That allegation refers to the council members’ support of 16-121, supporting the Standing Rock Lakota tribe and opposing the Dakota Access Pipeline, and 17-019. Aderhold, Lewis and Reynolds voted for Resolution 16-21, with Mayor Bryan Zak breaking a tie vote to pass it on Nov. 21, 2016.

While Alderhold, Lewis and Reynolds sponsored Resolution 17-019 on introduction, only Reynolds voted for it. The resolution failed 5-1.

Reynolds said the discussion shown in the emails is not uncommon and has happened in other behind-the-scenes discussions as council members consider upcoming business. The emails aren’t “a smoking gun,” as some of the recall supporters allege, she said.

“That kind of back-and-forth goes on all the time,” she said. “That was all legitimate. You might not have liked what we were talking about, but we weren’t doing anything wrong.”

Former Homer City Council member Barbara Howard, and a former longtime city clerk in California, agreed that council members often discuss items before they appear on the final agenda. It’s also not uncommon for citizens to ask council members to add something to the agenda or to introduce a resolution supporting a position.

“Citizens can ask us to place something on the agenda, because frankly that’s the only route it can go on,” she said.

For the “inclusivity” resolution, that started with both Spence and Reynolds. Spence, a founder of Citizens AKtion Network, a group formed after the election of Trump, proposed the resolution to Aderhold.

The emails start with Spence sending his version to Aderhold’s private email and Aderhold forwarding it to her city email address. Lewis then comes into the conversation. The Spence anti-Trump version included the “whereas” clauses critical of Trump that many citizens objected to in emails and public testimony. That never became the final resolution, but at one point it was submitted to the city clerk to be put on the agenda.

Last June, Reynolds had considered proposing a nondiscrimination ordinance that would include lesbian, bisexual, gay and transsexual rights similar to one passed in Anchorage in 2015. She said public emails include exchanges between her, Anchorage Assembly members and American Civil Liberties Union Alaska officials on a proposed ordinance. Reynolds said she dropped it when she decided it would be difficult to pass in Homer.

In January, Reynolds then considered a sanctuary city resolution. Using as a template a resolution passed in Olympia, Wash., one email shows a draft she wrote. On Jan. 31, she submitted the city clerk a placeholder title for a sanctuary city resolution to be put on the agenda. On Feb. 2, Mayor Zak wrote that “I would not like us to undertake this at this time.” Reynolds said she stepped back from working on a sanctuary city resolution.

She then heard of the resolution Aderhold and Lewis had in the works, and dropped her sanctuary city resolution and joined them as a sponsor on what Reynolds came to call the “inclusivity” resolution.

As seen in a Jan. 29 email, Spence’s anti-Trump resolution had a clause that says “the city of Homer will not cooperate with federal agencies in detaining undocumented immigrants unless such actions are supported by court-issued federal warrants.” In the final version submitted to the clerk, that clause was changed to “the city of Homer will cooperate with federal agencies in detaining undocumented immigrants when court-issued federal warrants are delivered.”

Aderhold also submitted in an email as background a report by Mijente, an immigrant rights group, “What Makes a City a Sanctuary Now?” That report defines “sanctuary” as “local policies that limit when and if local law enforcement communicates with, or submits to, (often unconstitutional) requests from federal immigration agents.”

Aderhold, Lewis and Reynolds initially wanted the inclusivity resolution on the Feb. 13 meeting agenda, but missed the deadline to submit items for the agenda.

Reynolds shared the anti-Trump version resolution with people interested in the issue, including Jeremiah Emmerson, a citizen active in political causes, including cannabis legalization. He put it out on the Homer Communications Facebook page. The post generated a storm of opposition, as seen by emails starting Feb. 16 that came to the clerk’s office. Aderhold and Reynolds said they did not intend for the draft to be published.

Howard said in her experience draft resolutions wouldn’t be shared with the public and would be clearly marked “draft.” She said it’s common for council members to discuss drafts before submitting them for public review.

Howard saw the anti-Trump resolution and said it was inappropriate because of its negativity. Coincidentally, council member Shelly Erickson contacted Howard for her guidance on amending the anti-Trump version. Howard made some suggestions, she said.

In an email on Feb. 18, Emmerson also submitted some suggested revisions, and Aderhold and Reynolds incorporated those in their final revision. Howard said her changes were similar to the final version, so she didn’t pass them on.

Aderhold said a lot of people were confused by the process, with some thinking the draft resolution posted by Emmerson had been passed by the council.

Even when the revised Resolution 17-019 came out, many people testified on the anti-Trump version.

“They loved the other one because it gave them more fuel,” Howard said. “They refused to comment on the one that was before them. On top of that, when the council votes no, they’re still after them.”

Howard said much of the discontent could have been avoided if the draft resolution had first been run by City Manager Katie Koester and City Attorney Holly Wells.

“They can at least bounce it off her and the attorney so they don’t look like buffoons,” Howard said.

Reynolds said in retrospect she might have done things differently.

“I have things for sure I feel like I could have done better, but I didn’t do anything wrong, legally or any other way,” she said.

Michael Armstrong can be reached at michael.armstrong@homernews.com.