The plans before the Legislature to use the Permanent Fund’s investment returns to pay for government have much in common, while their differences exemplify the priorities of their sponsors. The plan that is ultimately chosen will go a long way toward shaping the relationship Alaskans have with their state government.

The Alaska Permanent Fund Corp. Board of Trustees on Feb. 19 got rundowns of the three ideas in “to the point” presentations from the proposers themselves, Anchorage Republicans Rep. Mike Hawker and Sen. Lesil McGuire and officials from Gov. Bill Walker’s administration.

Legislators largely agree that filling the state’s $3.5 billion-plus budget deficit will require some utilization of the Permanent Fund’s earning power. The bigger lift could be getting the public on board, as Alaskans have become detached from how their government is funded, each of the presenters noted.

Hawker, a vocal critic of many Walker policies, commended the governor for his effort to “reconnect Alaskans to the financial and budget decisions made by their public officials,” through his overarching fiscal plan.

“We have been blessed in this state for the past 30 years with untold wealth, wealth that is the envy of every state in the union and probably three-quarters of the world. Through the earnings we’ve had from our oilfields, we’ve been able to pay for every needed and desired government service as well as distribute a portion of that wealth to individuals in the form of Permanent Fund dividends,” Hawker said. “We’ve paid for both necessities and we have had the luxury of being able to distribute money back (to the public), which has been wonderful.”

However, the combination of ever-declining oil production and unforeseen low prices will force changes to the status quo, according to Hawker.

“We are at an economic crossroads in the state wh

Alaska would need Alaska North Slope crude prices to rebound from the $30 per barrel range to nearly $110 per barrel to balance the budget at status quo.

McGuire, a 15-year veteran in the Legislature, said she “gasped” when she first learned that upward of 90 percent of state revenue is tied to the oil industry.

“It made me sick to my stomach to think that every year you would get a fall and spring (revenue) forecast based on hypotheticals regarding a single commodity of crude oil that is extremely volatile and then make decisions that affect every Alaskan’s life profoundly,” she said.

Hawker and McGuire are not seeking re-election this fall.

The Permanent Fund ended calendar year 2015 at $52.3 billion, with about $6 billion of that being realized, spendable investment revenue in the fund’s Earnings Reserve Account. Unrealized income and the amount currently committed to the 2016 dividend raise the value of the Earnings Reserve to about $8.1 billion.

At that size, Alaska is better off than other governments with similar funds, according to Attorney General Craig Richards, who is also a member of the Fund Board of Trustees.

He said Alaska’s Permanent Fund, when compared against the state’s average annual spending, is the largest “sovereign wealth” style fund in the world.

Walker laid out his ambitious New Sustainable Alaska Plan in early December. While it includes ongoing budget cuts and a suite of industry and personal tax hikes, the lynchpin of the proposal, the Alaska Permanent Fund Protection Act, relies on Fund returns to pull up to $3.3 billion for government services each year.

The Alaska Permanent Fund Protection Act would significantly re-plumb state coffers and transform the fund into a basic annuity. It would shift petroleum production taxes and the 75 percent of available royalty revenue into the Earnings Reserve Account. From there would come the $3.3 billion annual “allowance,” which, when combined with other revenues and further budget cuts would balance the state budget by the 2019 fiscal year, according to the administration.

Revenue Commissioner Randy Hoffbeck said the governor’s plan would allow the state to disconnect its annual budgets from a commodity with high price volatility and thus stabilize government spending to support economic growth in the state.

All of Alaska’s petroleum tax and “other” revenues have historically gone directly to the state’s General Fund, along with 75 percent of resource royalties.

The remaining 25 percent of royalties is constitutionally mandated to the Permanent Fund principal, or corpus.

That system has led to the state “chasing oil prices” and resulted in highly cyclical, and unhealthy spending, Richards said.

“When your economy is doing well (because of high oil prices) is not when you want your large capital budgets,” he commented. “You want your large capital budgets probably when your economy is not doing as well.”

The same pattern can be seen in the state’s operating budget, Richards noted.

Last year lawmakers cut roughly $800 million — about $400 million each from the operating and capital budgets in response to the oil slide and declining state revenues that began in the third quarter of 2014.

“That’s just sort of the way governments around the world work; you spend the money when you get it,” Richards said.

The actual draw on Fund earnings would be about $2.3 billion in the early years of the plan, as oil income would contribute a little more than $1 billion to the Earnings Reserve at low prices, according to Revenue projections.

“We’re housing these volatile revenue streams into a large savings pot and we take out of that savings pot a fixed amount every year,” Richards said.

To date, Permanent Fund Dividend payments have been the only draw on the Earnings Reserve Account. Legislators over the years have shown discipline towards the account despite being able to access its funds with a simple majority vote, Richards said.

The administration is betting that discipline continuing once the account is funding government to prevent overdraws.

A $3 billion transfer from the Constitutional Budget Reserve, or CBR, savings account to the Earnings Reserve would jumpstart the process and help the fund weather potential down years.

Currently, the CBR has about $8.7 billion available for appropriation.

The annual draw would be adjusted for inflation starting in fiscal year 2020, Richards said.

An Earnings Reserve starting at about $13 billion would provide about four years of funding and be a buffer from individual years of poor Fund returns.

The Alaska Permanent Fund Protection Act would require average annual investment returns of 6.9 percent, according to the administration.

The annuity-like draw could deplete the Earnings Reserve faster than the Percent of Market Value, or POMV, draw proposals by Hawker and McGuire, Richards acknowledged, because a POMV plan pays out less following years of poor returns.

However, a four-year review cycle of the plan’s draw and Fund returns would allow lawmakers to adjust spending up or down while maintaining the sustainability of the fund, Richards and Hoffbeck said.

On the flipside, a POMV approach adds to available state funds but doesn’t address volatility in petroleum revenue, Richards said. The drastic spending swings could still occur.

He said a $2.5 billion swing, positive or negative, in the fund’s value would equate to roughly $100 million more or less available for a sustainable draw each year under the administration’s plan.

As for dividends, the administration borrowed an idea from McGuire’s plan to tie the payment to Alaskans to resource income, thus connecting Alaskans to their state’s fiscal situation.

After a guaranteed $1,000 dividend in the first year of the plan, the dividend would be 50 percent of annual resource royalty revenue — somewhere between $800 and $1,000 per person in the coming years based on the state’s future oil price and production estimates, Hoffbeck said.

A year of current oil prices in the $30 range would roughly equate to a $400 check for each Alaskan, he noted.

The longstanding dividend formula distributes half of the fund’s annualized five-year rolling average of realized earnings each year.

“One of the things we really tried to do with this plan is to make the dividend payment somehow reflect the state’s ability to pay the dividend, so we don’t end up in a situation like this year when we’re paying a historic high dividend (about $2,000) at a time when the state is in a historic difficult time financially,” Hoffbeck said.

McGuire’s plan would provide a slightly higher dividend with nearly 75 percent of royalty revenue being devoted to the checks. A 0.5 percent share of royalties would add to the state Public School Trust Fund.

The final dividend and government funding amounts are little more than a balancing act. Adding to one ultimately means pulling from the other and the final shares are debatable policy decisions, Hoffbeck and McGuire said.

Both also addressed the misconception that the annual PFD checks are constitutionally protected and that the proposals to change the dividend calculation would automatically cut the payment amount.

Overall strong financial market performance since 2010 has led to large PFDs the last two years, but a look back farther shows volatility in the dividend as well.

Hoffbeck said over the last 12 years four PFDs have been more than $1,500; four have been between $1,000 and $1,500; and four have been less than $1,000.

McGuire said pushback to changing the dividend calculation comes from an emotional attachment many individuals have with the annual October check.

“The constitutional amendment that was put forward by (former Gov. Jay) Hammond — of course approved by the House and the Senate and then put on the November 1976 ballot — was to create a Permanent Fund, not a Permanent Fund Dividend or a Permanent Fund Dividend Program and this is a point that is still lost in the public,” she said.

McGuire’s Senate Bill 114

McGuire quietly introduced Senate Bill 114 last April while a long and ugly battle over the operating budget was just beginning.

It was the first of the three plans now under review in the Legislature to utilize the Permanent Fund’s earnings for state operations.

She proposes to use an annual draw equal to 5 percent of the rolling five-year average market value of the Permanent Fund, or POMV, from the Earnings Reserve to add $2 billion, and hopefully more in future years, to the General Fund in fiscal year 2017 beginning July 1.

Allocations of oil production taxes and other revenues would continue to flow into the General Fund.

The Permanent Fund Board of Trustees passed resolutions in 2000, 2003 and 2004 — the last period of sustained low oil prices — supporting a 5 percent POMV spending limit for the Fund.

McGuire said the recognition of the Legislature’s authority to statutorily restructure the payout of Fund earnings has been a “light bulb moment” for some legislators.

Simply, her plan would not balance the budget, but it would put the state in a better situation and give lawmakers more time to debate further budget cuts or other revenue options while keeping dividends intact in some form.

The process of transforming state government funding must be taken in pieces, she said. McGuire and Hawker both said their plans hit on what they feel is politically possible to accomplish over what might be a philosophically perfect solution.

“If we could just get the Legislature to adopt this one piece, whether it’s my bill or another bill, but just examine the role of the Permanent Fund itself — whether it’s appropriate to have some distribution to the government,” McGuire said. “If we could just do that one thing it would be good and in the process of doing that the conversation can begin in earnest about the size and cost of government that Alaskans want and what they’re willing to pay for.

“This is a conversation we have needed to have for decades and it is at the heart of what will make this state viable in the future because Alaskans have been completely out of touch with what pays the bills.”

Hawker’s House Bill 224

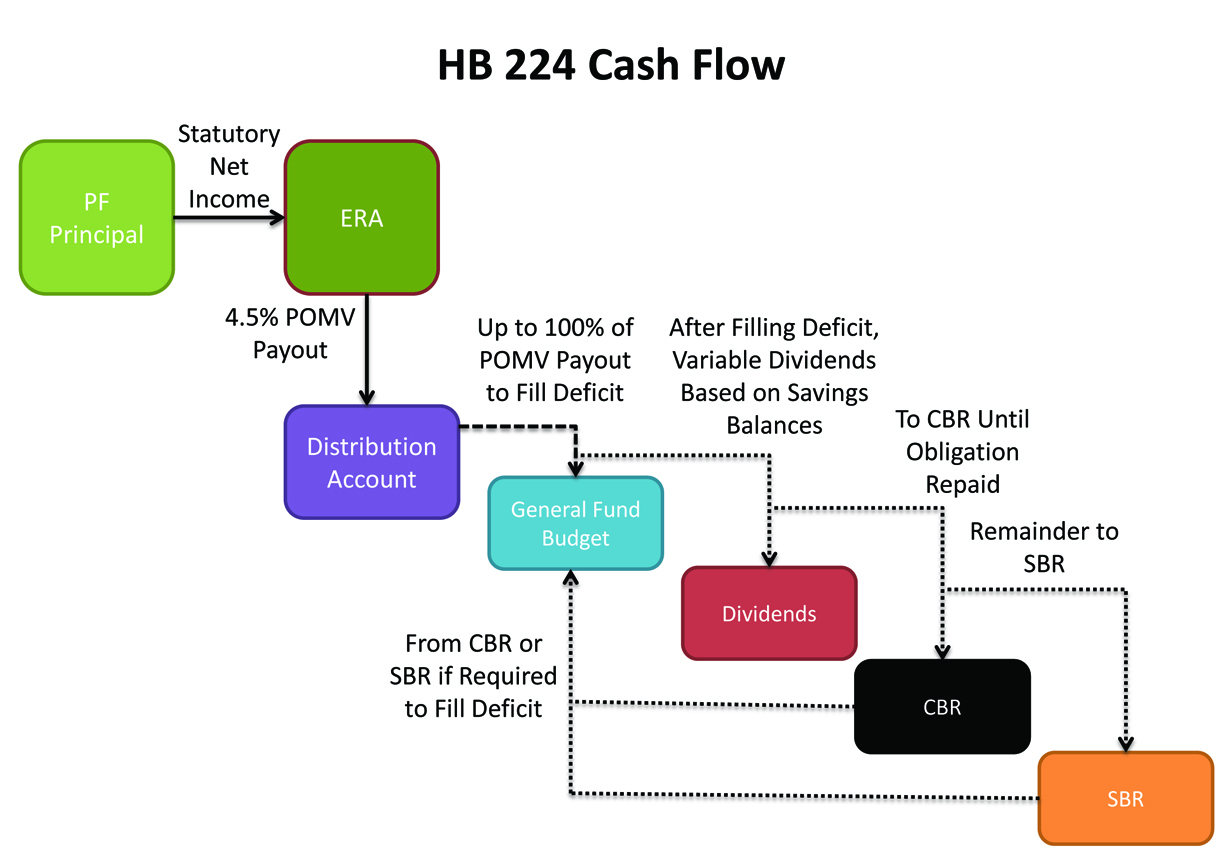

Hawker’s House Bill 224 prioritizes a balanced budget over everything else, including dividends.

It’s based on the “fiscal responsibility rule” of necessities over luxuries, Hawker said to the trustees.

“My bill simply says to the Legislature that we need to provide our schools; we need to provide our roads; we need to provide health and service benefits; we need to do all this before we pay dividends,” he said.

His plan has goals similar to the administration’s proposal, but reaches them more simply, he said. It uses savings to mitigate oil and financial market volatility.

With an annual draw equal to 4.5 percent of the Permanent Fund’s average market value, Hawker’s bill would draw about $2 billion from the Earnings Reserve to the General Fund each year.

Like SB 114, it would keep other current revenue flows in place, but the royalty cash used to pay dividends in the plans from McGuire and the administration, would also be used to close the fiscal gap.

Further budget cuts would also be needed.

Dividends could be paid in years of surplus, a determination that would be up to the Legislature and also depend on whether state savings accounts need to be replenished as well.

The 2016 fiscal year dividend appropriation could be paid in one year or spread over several years — another legislative decision — to wean Alaskans off of the annual check, he said.

In years of particularly high market returns the Legislature could also appropriate excess POMV revenue directly into the corpus of the Permanent Fund to continue growing the fund, Hawker said.

“My bill specifically has provisions in it that very clearly state the Legislature is not in any way prescribed from making any appropriation that would move money anywhere,” he said, noting he plans to add further clarification that a 4.5 POMV appropriation to the General Fund is not required either.

Hawker’s POMV would be calculated using the average Fund value from the first five of the previous six years. As a result, the POMV draw would be based on finalized, audited Fund results, rather than using preliminary figures from the current fiscal year to calculate the draw.

McGuire said she will likely add the “five out of six” provision to SB 114 as well.

A Fund perspective

Greg Allen, head of the fund’s consulting firm Callan Associates Inc., shared the prospective impacts each of the plans could have on the fund with his fellow trustees.

The results? They’re all about the same.

“I’m happy to report that all of these plans in the median case result in a slightly higher market value” for the fund, Allen said.

The full viability of each plan, as originally constructed, would be hurt by poor projected fund returns this year, he noted.

Callan is forecasting a 3.7 percent loss in fiscal year 2016, which ends June 30. Through Feb. 19 the total return was down 5.6 percent from the start of the state fiscal year, Allen said.

The Permanent Fund’s value was $50.2 billion as of Feb. 22 compared to the $52.3 billion it held at the end of the 2015 fiscal year last June 30.

When the poor expected return for 2016 is accounted for, the inflation adjusted value of the fund after 10 years would be $49.6 billion under the Alaska Permanent Fund Protection Act, $50.2 billion under McGuire’s SB 114 and with a slightly smaller POMV draw, $51.7 billion under Hawker’s HB 224.

The fund’s status quo ending value for 2016 is projected at $48.6 billion. The status quo market value of the fund, in 2015 dollars, would be $63.1 billion after 10 years, Callan estimates.

While the fund would benefit the most from high oil prices under the governor’s plan because it places oil revenues in the Earnings Reserve, the plan also has the highest risk of hitting a draw limit.

The governor’s Permanent Fund Protection Act would require a draw recalculation under 30 percent of market scenarios, while the POMV plans would need to be reworked in 25 percent of market forecasts, according to Callan.

Hoffbeck emphasized the importance of management to remain free from state needs regardless of the plan chosen by the Legislature.

“It is absolutely critical that the investment side has to stay autonomous, independent from the spending so that the trustees and the Permanent Fund don’t get into a place where they have to start making investment decisions to meet a budgetary requirement,” Hoffbeck said.

If that were to happen the whole system would begin to crumble, he said.

Elwood Brehmer is a reporter for the Alaska Journal of Commerce.

ere we can no longer afford to have everything we want,” he said.