A tsunami advisory issued by the National Weather Service Tsunami Warning Center on Saturday morning never escalated to an evacuation of the Homer Spit and low-lying areas around Kachemak Bay. The advisory followed an underwater volcanic eruption near Tonga in the South Pacific Ocean that happened about 6:30 p.m. Friday. The tsunami advisory was called off about 11 a.m. Saturday, Jan. 15. The warning covered most of coastal Alaska, Hawaii and the Pacific coast all the way to California.

According to the Associated Press, the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano caused tsunami waves up to 2.7 feet in Hawaii and up to 2.5 feet in California. The tsunami also hit Tonga. The BBC reported three people were killed and widespread damage to homes and businesses.

While a tsunami less than 2 inches washed up around the bay, another wave — this one in the atmosphere — woke up people in Homer, Seldovia and around Alaska.

“It wasn’t something I was aware of at that time. I heard something in the middle of the night,” said Kasey Aderhold, a Homer seismologist now telecommuting for Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology of Washington, D.C. “I definitely woke up to what I thought was a car parked outside playing really heavy bass.”

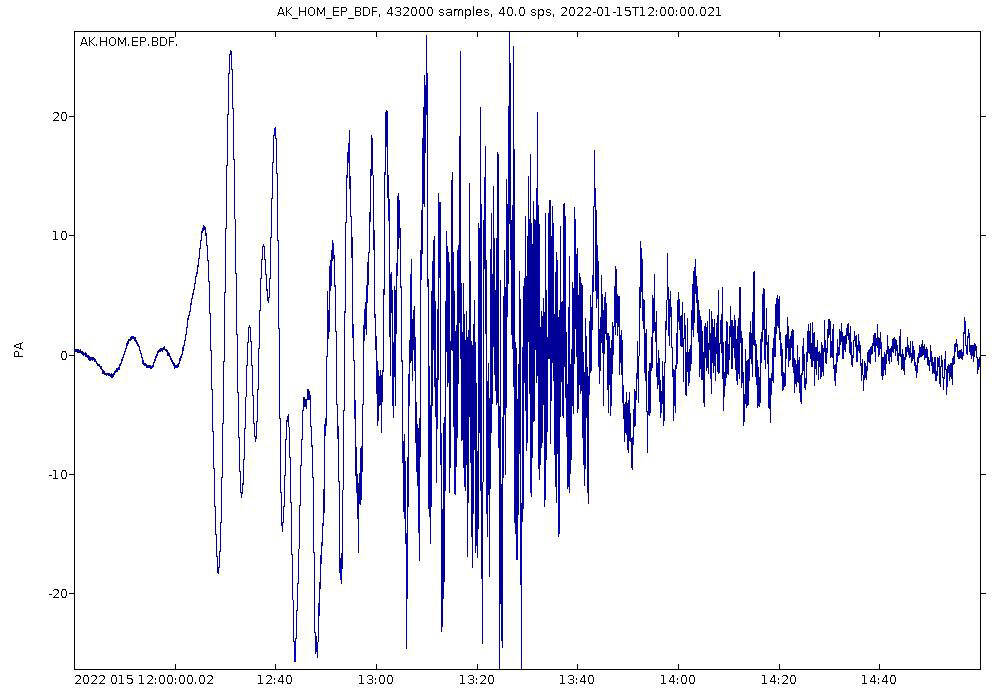

That was something she was used to when she lived in D.C., but not in Homer. Aderhold later thought it might have been snow falling off her roof or maybe an earthquake. When she woke up on Saturday and looked at data from a seismic station on Baycrest Hill, she saw a clear signal that a pressure wave had hit Homer at about 3:20 a.m. Social media showed reports of people from all over Alaska reporting hearing strange pops and booms.

“The weird part is that it was audible,” Aderhold said. “Everyone got the pressure wave around the world. The fact that I could hear it — I don’t think anyone has a good explanation yet as far as I can tell.”

Measurements on worldwide instruments of the pressure wave showed the initial wave hitting sensors and then circling around the earth, Aderhold said.

Bretwood “Hig” Higman, a geologist in Seldovia, said he also is stumped at what caused the pressure wave to be heard. The pressure wave itself would have been caused by the sudden explosion of gas, steam and ash from the undersea volcano. Higman said if you think of the atmosphere as a pool of fluid, the wave would be a ripple in the surface of the atmosphere. That wave traveled faster than the speed of sound.

“That pressure wave comes along, it arrives in Alaska and, for some reason that’s mysterious, produces noise that we can hear,” he said.

Higman said he wondered of the audible sound had to do with weather conditions or the wave hitting the coastal mountain ranges of Alaska.

“It gets further and further into speculation,” he said. “… I’m very interested to know how how it was we ended up with these audible sounds with something that should not have been audible at all.”

A Twitter feed Aderhold got tagged into had seismologists, volcanologists and atmospheric physicists weighing in.

“They haven’t had a whole lot of events to compare to,” she said. “I feel like this is treading into one of those areas where maybe it’s this, maybe it’s that. … There should be some good papers to come out of it.”

Although locally catastrophic, the Tonga tsunami wasn’t like the big subduction zone earthquake type events of the 2005 Indonesian or 2011 Japanese tsunamis. Those are caused by a large displacement of water, Aderhold said.

The Tonga tsunami might have been what Higman called a volcano-meteorological tsunami or a meteotsunami.

“What that is, that change in pressure in the atmosphere, it pressed on the ocean surface,” he said. “If it propagates close enough to the speed a tsunami would travel, it propagates its energy into the ocean. … I think it’s clear that this was a case where this atmosphere wave, this gravity wave, became a tsunami wave as it traveled.”

Such a tsunami should cause geologists to rethink how tsunami hazards can be modeled, Higman said.

“This idea, it’s not so much a fringe idea that people didn’t believe, but that people didn’t wrap their heads around it prior to this event,” he said. “… We need to figure this out so we won’t be surprised next time.”

Reach Michael Armstrong at marmstrong@homernews.com.