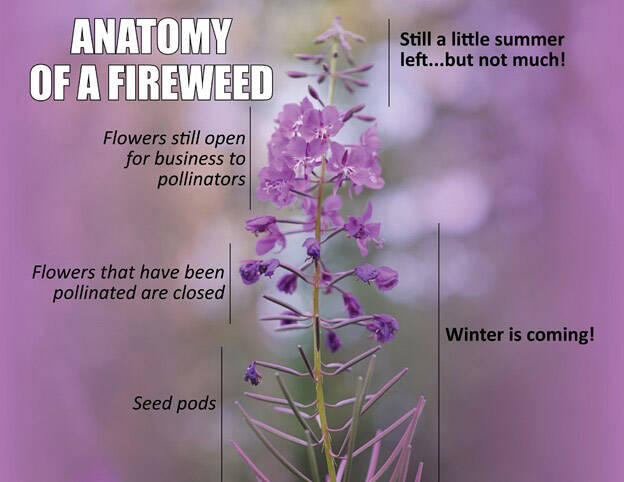

Alaska’s short, sweet summer is usually in full swing by the time you really notice it. “Better hurry and enjoy it,” the fireweed says as blooms march up its stem.

Another beautiful Alaska summer gone by, marked by fireweed flowers going to seed as salmon runs shift to Coho and start to dwindle. As the saying goes: “When fireweed turns to cotton, summer will soon be forgotten.”

If you’ve visited Kenai National Wildlife Refuge or taken a drive through the Kenai Peninsula recently, you’ll notice a contrast along the blackened scar left by the Swan Lake Fire of 2019: carpets of fireweed, easily visible from the Sterling Highway.

Fireweed gets its common name in the United States because it’s notoriously associated with fire landscapes. It quickly colonizes disturbed areas, including fire scars, logged land and oil spills.

It was one of the first plants to appear after the catastrophic eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington, and it even took over urban burned ground after London was bombed during World War II. (In England, one of its common names is “bombweed.”)

It disperses by thousands of seeds that fly on little silky tufts each fall. Each fireweed stalk can have 80,000 seeds, helping the plant quickly spread.

Flowers are replaced by long cylindrical capsules full of silky fluff that open up at the end of summer, parachuting their attached seeds into the wind.

Fireweed also spreads underground through a system of stems called rhizomes. When a fire moves through, the rhizomes usually survive the burn and can quickly grow again the following summer.

This underground network can help stabilize burned or logged soil from eroding, and the plants help recycle nutrients back into the earth.

A fun fact about fireweed is that the flower stalks are usually around 2- to 4-feet high, but can grow up to a monstrous 9 feet. On the tundra, fireweed can be tiny.

Where there’s fireweed, there’s wildlife. Bears chow on the tender young shoots in June and deer browse the flowery stalks. Moose, caribou, muskrat and hares also forage on fireweed.

Fireweed attracts pollinators too, including native bumblebees and various solitary wild bees. It’s the most fed upon species for honeybees kept by Kenai Peninsula beekeepers from Homer to Seward because of its prevalence.

There are many traditional human uses for all parts of the plant, which is high in vitamins C and A. Young stems can be boiled and eaten like asparagus, the dried leaves can be made into tea, and the flower nectar can be used in honey, syrup and jelly.

Even the silk seed tufts have been used, as padding or incorporated into weaving. Medicinally, fireweed has been used to treat cuts and boils, and the extract has anti-inflammatory effects. To make your own fireweed jelly, you’ll need about 8 cups of the flowers to boil into juice.

Lisa Hupp is a Communications Specialist for the National Wildlife Refuge System in Alaska and Katrina Liebich is public affairs specialist with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service’s Alaska External Affairs team. Find out more about refuge events, recreation, and more at kenai.fws.gov or Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/kenainationalwildliferefuge. To find more Refuge Notebook Articles go to https://www.fws.gov/kenai-refuge-notebook.