Homer High School students recently had a hands-on Alaskan history learning experience that culminated in a temporary exhibit of their semester projects at the Pratt Museum.

Students participating in HHS’s Alaska History class had the opportunity to choose artifacts for study from the Pratt Museum’s permanent collection. During this fall semester, starting in September, they researched their chosen artifacts and their connections to Alaskan history, and prepared educational displays to showcase what they learned. The exhibit was open from Dec. 2-6 in the downstairs classroom at the museum.

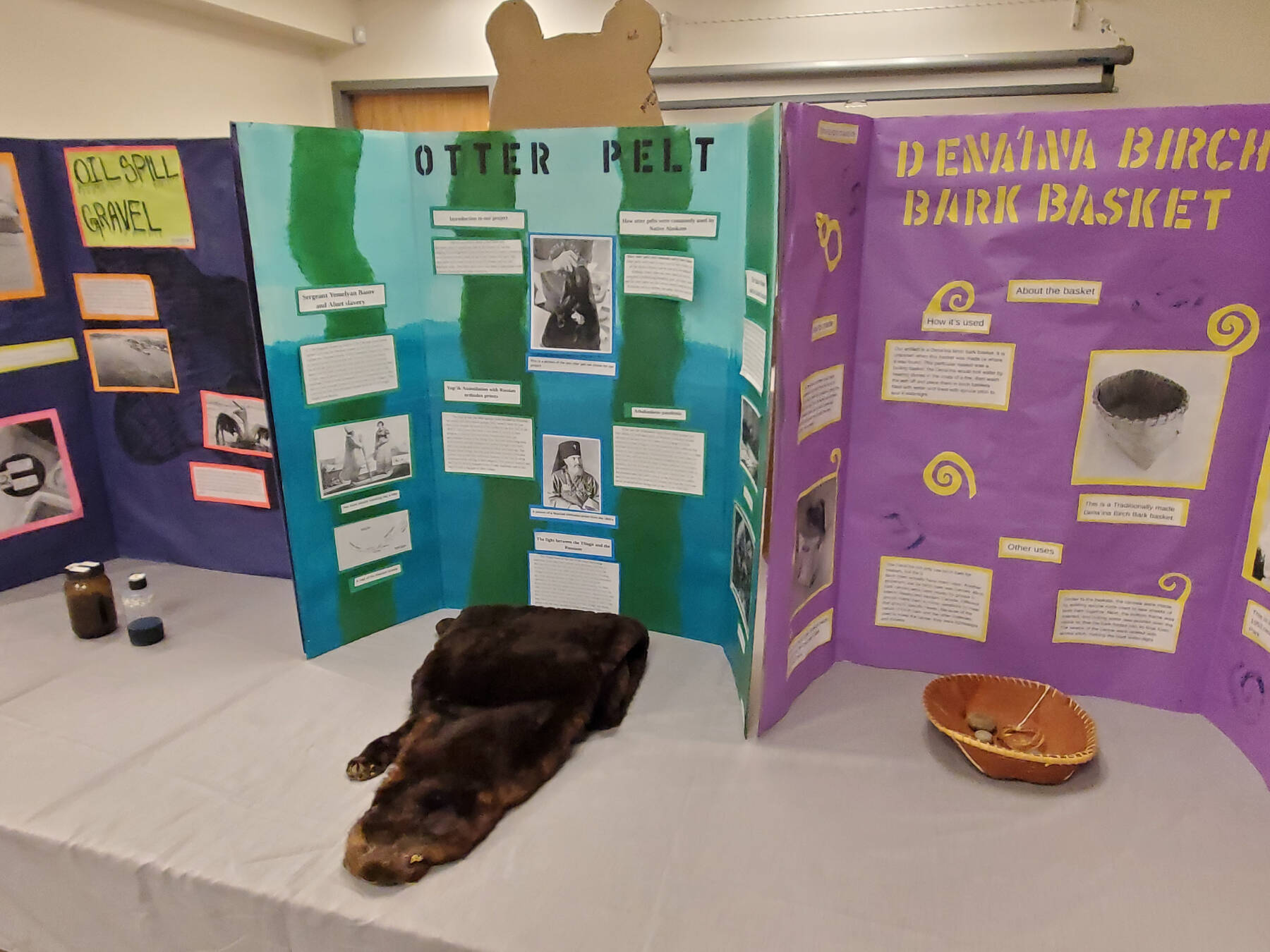

Approximately 60 students worked together in small groups to create 27 displays for the place-based exhibit. The students’ chosen items, ranging from Alaska Native artifacts to relics from Alaska’s pioneering days to more recent events, were also displayed as part of the exhibit. Pratt Museum Education and Public Programs Manager Maghan Monnig said Friday that the ages of the artifacts chosen ranged across the spectrum of Alaska history, from potentially pre-contact up to the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

Monnig said that the exhibit, created through a partnership between the museum and HHS language arts teacher Lucas Parsley, who also teaches the Alaska History class, started last semester as a “guinea pig” collaboration.

“The exhibit was only up for an evening, and we got feedback from the students that they wanted it to be longer than that,” she said. “But originally, Lucas Parsley approached the museum about collaborating on a type of project, and we came up with the students making their own exhibit.”

Monnig said that she selected a number of items from the museum’s permanent collection that could be displayed to the public for a longer period and would represent a wide range of Alaska history.

“To have permanent collection items out for more than an evening, they need to be able to fit in a case, and to fit as many items as we needed to, we had to make sure they were still pretty small,” she said. “I pre-picked items from our collections so everyone had a choice with what they wanted to do.”

Some of the items on display included toy soldiers, a snowshoe hare pelt, an adze, a halibut hook, a piece of etched slate, a berry scoop, traditional basketry, a postal letter scale, a harpoon head, ulus, a sample of North Slope crude oil, and more. Monnig said that Parsley had requested that “as much of Alaska history be represented as possible.”

“From these items, some of the students took it in a whole other direction that I wouldn’t have even thought of, initially,” she said.

For example, one group that chose to study the postal scale broadened their perspective beyond the item itself, and were able to connect their chosen artifact to Alaskan mail ships such as the Starr or the Dora and how the mail system in Alaska worked in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Monnig said that the oldest artifacts made available to students for the project were the etched slate and harpoon head, which were donated anonymously to the museum a number of years ago.

“They were most likely archaeological items, so they could be at least a thousand years old,” she said.

Monnig said that the museum is interested in continuing the collaborative exhibit as long as the high school is willing, and that she and Parsley had discussed finding a different approach to doing the collections research.

“We aren’t quite sure what that is yet, but we’re going to start thinking of other ideas for how to get students involved in the museum,” she said.