The experiment: Kenai becomes an agricultural test site — Part 3

Published 9:30 pm Wednesday, November 26, 2025

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Presidential Executive Order #148, in January 1899, had set aside 320 acres of land near Russian Orthodox Church property in the village of Kenai for the creation of an agricultural experiment station. The superintendent of this new station, H.P. Nielsen, under the supervision of Sitka’s Prof. C.C. Georgeson, continued to expand his farming operation and adjust to village life.

As 1900 became 1901 in the remote village of Kenai, agricultural experiment station superintendent Hans Peter Nielsen—who hailed from rural Kansas—had not been home since accepting his post in the spring of 1899. He clearly missed the environs in which he had grown up and the mostly white, middle-class citizenry of which he had been a part.

In Kenai, as one of very few white residents, he found himself surrounded by a mix of Russian and Alaska Native influences, even as he was fashioning a distinctly non-Russian/Native enterprise at the village periphery. In mid-winter 1900-1, he continued to gravitate toward his comfort zone, as he noted in a March 1 letter to the editor of the Lincoln Republican.

“There has not been so many white men here this winter as there were last,” he wrote. “But I have spent a very pleasant winter. We white men got up a big Christmas dinner … in my cabin, as I had the most room and the best stove.” He moved his bed outdoors for the evening to accommodate 12 guests, all white men.

His guests included store owner and manager William Dawson, crafty entrepreneur P.F. “Frenchy” Vian, future postmaster George Mearns, and hunting guide William Hunter. They feasted on scallops, oysters, macaroni and cheese, stuffed grouse, potatoes, tea, mince pies, custard cake, raisins and nuts, and some sort of alcoholic punch.

“We had a glorious time that night,” said Nielsen. “Next day, some of the boys didn’t feel so glorious.”

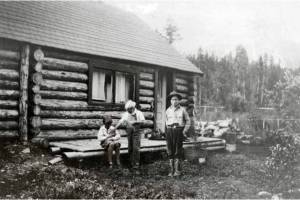

Nielsen filled most of the remainder of his letter with news about his Kenai Station, with a focus on his work to construct a government house on station grounds. He had cut house logs and used his oxen to drag the logs to the building site.

He had started the building project in late autumn, after he had finished working with his crops. As a result of his late-season construction start, he had to battle snow, which came before the ground at the station had fully frozen, and which covered his log piles and his tree-dragging trails.

Some of the spruce he planned to cut stood on the far side of two small swamps.

“The snow coming so early,” Nielsen wrote, “not more than an inch thick of ice had formed on the water [in the swamps], after which the water had settled away and left holes two or three feet deep underneath. It would carry a person all right, but when I got the oxen on there, they went through and stuck in the mud beneath, and there we were.

“I had to unhitch and then get them out one at a time, then take the sled apart and haul it out by hand,” he continued. “So I had had to take the ax, break in the ice and tramp down the snow so it would freeze, and when I tried it again a few days later, I got across all right…. [To] make a long story short, I got through hauling [the logs] by New Year’s and through hewing them February 21, and at the present time have about half of them in the wall. I expect to get them all in by April 1.”

By the time the 1901 growing season had ended, Nielsen had been in Alaska for more than two years without returning to Kansas. He was homesick.

His visit to Kansas in late November 1901 provided him a welcome respite and a big surprise for his parents, who had not been informed he was coming. He told the local newspaper that he would have to start back for Alaska in February 1902 in order to assure his return to the Kenai Peninsula by March.

His brother, Harold Nielsen, informed the paper in early March that Hans had arrived safely in Kenai after a stormy steamship passage that had left him more seasick than at any time in his life.

A New Direction

Hans Nielsen’s accomplishments in Kenai had not gone unnoticed by his boss, Prof. Charles Christian Georgeson, in Alaska’s capital city of Sitka.

In his annual report (July 1, 1901, to June 30, 1902) to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Georgeson lauded his subordinate’s efforts: “Mr. H.P. Nielsen … deserves much credit for the large amount of work he has accomplished. In addition to the cultivation of about 7 acres in many kinds of experimental crops and vegetables, he has cleared, broken and put in condition for spring seeding about 8 acres of new land.

“For all this work,” he continued, “he has only had one man hired by the month, and for a few days occasionally one or two native laborers…. He works hard, faithfully and intelligently.”

Nielsen had planted apple, cherry and plum trees, plus raspberries, blackberries, gooseberries, strawberries and currants. Georgeson was particularly pleased with Nielsen’s production of vegetables and grains—he had put up about five tons of hay from native grasses—but Georgeson also had grander designs in mind.

He noted that Nielsen had completed construction of the new Kenai Station quarters and was preparing to greatly enlarge the barn. Georgeson had authorized Nielsen to spend $100 to buy the lumber from a defunct cannery building—75 feet long by 25 wide, with a shingled roof—to use in the expansion.

Georgeson foresaw moving the expanded facilities in a new direction. “I respectfully recommend,” he wrote to Department of Agriculture officials back in Washington, D.C., “that as soon as it may be practicable, a few more head of cattle be procured for this station and that our experiments then be extended on the lines of dairying and the production of beef.”

To that end, he believed that the area of cleared and cultivated land should be expanded from its then-current 15 acres to nearly 100 acres, for grazing and haying.

To kick-start this new animal-husbandry plan, Georgeson authorized Nielsen in early June 1902 to purchase from the Russian Orthodox priest, Father John (Ivan) Bortnovsky, a cow (obtained originally from Kodiak) and her four-and-a-half-month-old heifer calf. During the summer months, the cow produced 2,530 pounds of milk, an average of 29 pounds per day.

The new additions raised the number of cattle at the station to five, including two work oxen and one yearling steer. It was a good beginning, but considerable work still lay ahead if dairy and beef farming was going to become a viable enterprise in Kenai.

TO BE CONTINUED….