The experiment: Kenai becomes an agricultural test site — Part 5

Published 9:30 pm Wednesday, December 10, 2025

AUTHOR’S NOTE: A presidential executive order in January 1899 had set aside 320 acres of land near Russian Orthodox Church property in the village of Kenai for the creation of an agricultural experiment station. By 1904, the superintendent of the Kenai Station, P.H. Ross, under the supervision of Sitka’s Prof. C.C. Georgeson, was focused almost solely on dairy and beef production.

When Prof. Charles Christian Georgeson, in charge of all agricultural experiment stations in Alaska, assessed the progress at the Kenai Station between June 30, 1904, and July 1, 1905, he saw promise, with one caveat.

The promise involved improving cattle production. The caveat involved the difficulty of providing enough grain to feed those cattle during Kenai’s long, harsh winters.

By the summer of 1905, the number of cattle at the station had risen to 13 head. Station superintendent Pontus Henry Ross then sold one cow and one calf to Mr. O.H. Sleeper, of Sunrise, for $60. He also sold milk and butter locally, and Georgeson, after being informed of these developments, reiterated that he believed the future of the station lay in dairy and beef.

Ross ordered more dairy equipment to facilitate these efforts, and Georgeson began investigating the possibility of transplanting to Kenai a hardier strain of cattle, thus making them more resilient during the winter months.

But despite these moves, Georgeson fretted. He worried that poor growing seasons could derail the whole operation and prevent the Kenai Station from reliably producing enough hay for winter feed. Moreover, Kenai’s own inaccessibility could prevent “emergency feed” from being delivered, except by what he termed a “special conveyance.”

When he had decided to place a station in Kenai in 1899, Georgeson had not foreseen such problems—or perhaps had poorly considered the possibilities—as “it was expected that the peninsula would be settled by people who would work in the newly discovered placer mines [mostly Hope and Sunrise] and in the coal fields [at Homer], which were then being opened up … but neither the coal fields nor the placer mines have made any progress.”

It had also been hoped that more of the peninsula would be settled by this time, but transportation concerns tended to keep larger settlements closer to ice-free ports, such as Seward and Seldovia.

As a result, wrote Georgeson, “[It] is therefore recommended that steps be taken to remove this station to a suitable location somewhere on the [Alaska Central] railway, the place to be selected after the [rail] road is built and in operation.”

The end of the Kenai Station seemed thus preordained.

Building for the future, nevertheless

Still, Georgeson and Ross sought a silver lining.

In August 1904, the Kenai Station bought six hens from a local man. During that month, the hens, fed solely on table scraps, laid eight dozen eggs.

Ross continued to garden, with somewhat mixed results. Kenai experienced a frost on July 26, and insects infiltrated the garden, destroying nearly all of the cabbages and some of the radishes. Most of the vegetables and fruit, however, thrived.

Georgeson announced in 1905 that he intended to import black Galloway cattle, a traditional Scottish breed, to Kenai. “This is an extremely hardy breed,” reported the Alaska Forum, “whose habitat is a cold, damp climate, and [Georgeson] thinks they will thrive [in Kenai]. ‘They are the cattle which face the storm,’ said Georgeson. ‘All other cattle turn their tails to it. The Galloways have a thick covering of hair in their face and do not seem to mind the storm at all.’”

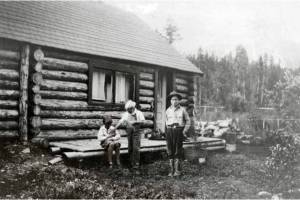

On July 12, 1905, the Alaska Packers Association cannery at Kenai burned, and Ross salvaged some fire-damaged tin from the cannery, coated it with tar, and then roofed three new buildings at the station—an 8×14-foot woodshed, a 14×20-foot blacksmith shop and a 14×20-foot implement shed.

Eleven head of Galloway cattle, shipped from Scotland, arrived in Alaska in April 1906. Six were sent to Kenai, the other five to Kodiak. According to the Seward Gateway at this time, Prof. Georgeson claimed to have “great faith that within a few years, large herds of Galloways, and possibly other hardy cattle [would] be successfully bred and raised in southern Alaska.”

Several head of Jersey cows had been previously kept at the Kenai Station, and Georgeson announced that he was considering breeding them with the Galloways to produce a tougher line of cattle that were also good milkers.

Ross resigned May 1, 1907, and was replaced by Missouri native James W. Gray, who had arrived as Ross’s assistant in 1906.

Additionally, Milton D. Snodgrass, another graduate of and instructor at Kansas State Agricultural College, was brought onto the experiment station payroll as the new superintendent for the Kodiak Station and as inspector for the Kenai Station.

From this point, Snodgrass replaced Georgeson as the Agriculture Department’s boots-on-the-ground representative in Kenai. Georgeson explained that Snodgrass could visit Kenai “in much less time and at less expense” from Kodiak than Georgeson could from his post in Sitka.

Soon afterward, Georgeson gave the final authority to Snodgrass to determine the fate of the Kenai Station.

End of the line

Except for a small garden, some grass plots and the buildings of Kenai Station, all 26 acres under cultivation in 1906-07 were sown with oats to provide hay for the cattle, which now numbered 22 head.

But Georgeson and Snodgrass determined that even that season’s healthy supply of hay was too little to support the overwintering of so many cattle, in addition to the station’s two work horses. After Oct. 1, 1907, they transferred 11 head of the station’s 13 Galloways to Kodiak.

The remaining cattle, on Snodgrass’s recommendation, were kept in Kenai during the winter of 1907-08. “A crop [of hay] at Kenai … will be sufficient to keep them during the winter,” Snodgrass told the Seward Gateway. “This would be wasted if [all] the cattle were moved this year.”

“The dairy work has not been pushed as vigorously this year as last because there was but little demand for butter,” Georgeson added, “while, on the other hand, there was a demand for milk, owing to much sickness among the natives.

“There has been no additional clearing of land or other improvements,” he continued, “because … it is the plan to transfer the entire equipment to Kodiak Station in the spring and to temporarily close the Kenai Station.”

Although the notion of reopening the Kenai Station would be held out for a number of years, Georgeson’s “temporary” closure would eventually become permanent.

TO BE CONTINUED….