The experiment: Kenai becomes an agricultural test site — Part 7

Published 9:30 pm Wednesday, December 24, 2025

AUTHOR’S NOTE: After the agricultural experiment station in Kenai closed May 1, 1908, Alaska station supervisor C.C. Georgeson had to decide the fate of the infrastructure at the decade-old facility.

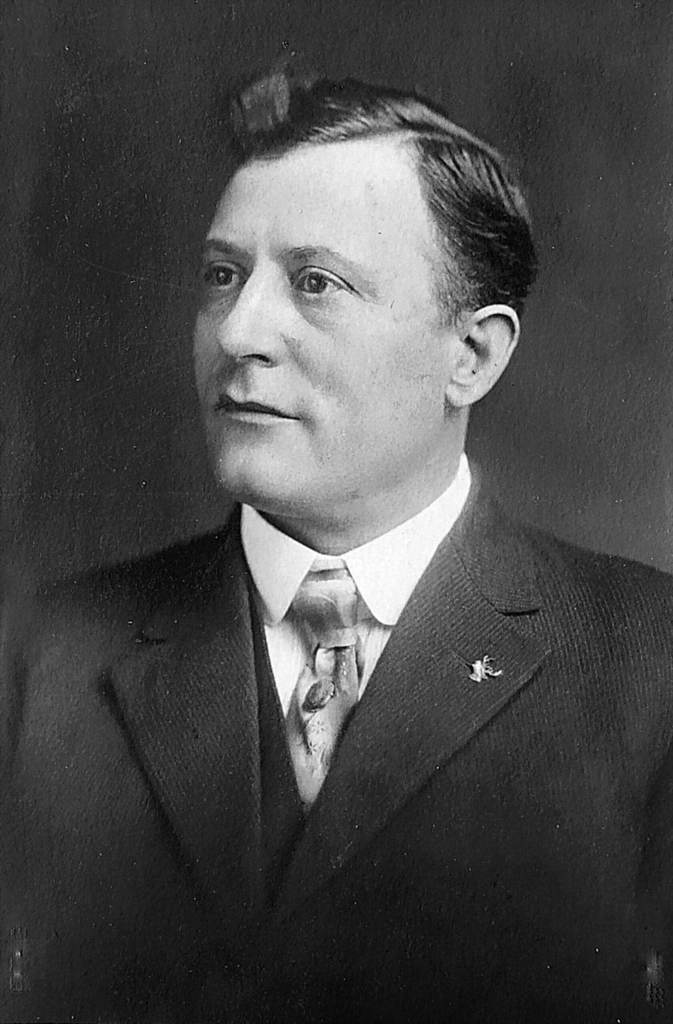

On May 1, 1908, Prof. Charles Christian Georgeson, supervisor of all agricultural experiment stations in Alaska, officially and “temporarily” closed the Kenai Station, which had begun its operations in the spring of 1899.

Over the next few years, two things became apparent: First, the closure of the experiment station was much more likely to be permanent than temporary. Second, it was not going to be easy to find another governmental entity to fill the on-site buildings and be willing to keep them in good shape.

Early on, Georgeson authorized a use-only permit for the Alaska Division of the U.S. Bureau of Education and left it up to Division Chief W.T. Lopp to see to the details. By 1912, however, it seemed clear that Kenai educators were not using the facility and that, instead, a variety of other uses were taking place.

Seward commercial freight haulers (and suspected moonshiners) Harry Hoben and Al Davis, of the Alaska Transfer Company, were keeping a team of horses in the Kenai Station barn. Judge J.H. Brownlow, the U.S. commissioner posted at Kenai, had been “provisionally authorized” to temporarily occupy the building. And P.F. “Frenchy” Vian, a friendly but somewhat shady hunting guide and storekeeper, had been given permission by Lopp to use the station house as his personal quarters.

Georgeson, stationed in Seward, knew about Brownlow, who had told him about the freighters, but he was unaware that Lopp had okayed Vian’s occupancy until the U.S. Forest Service—another division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture—asked for official permission to occupy the station grounds.

Muddied Waters

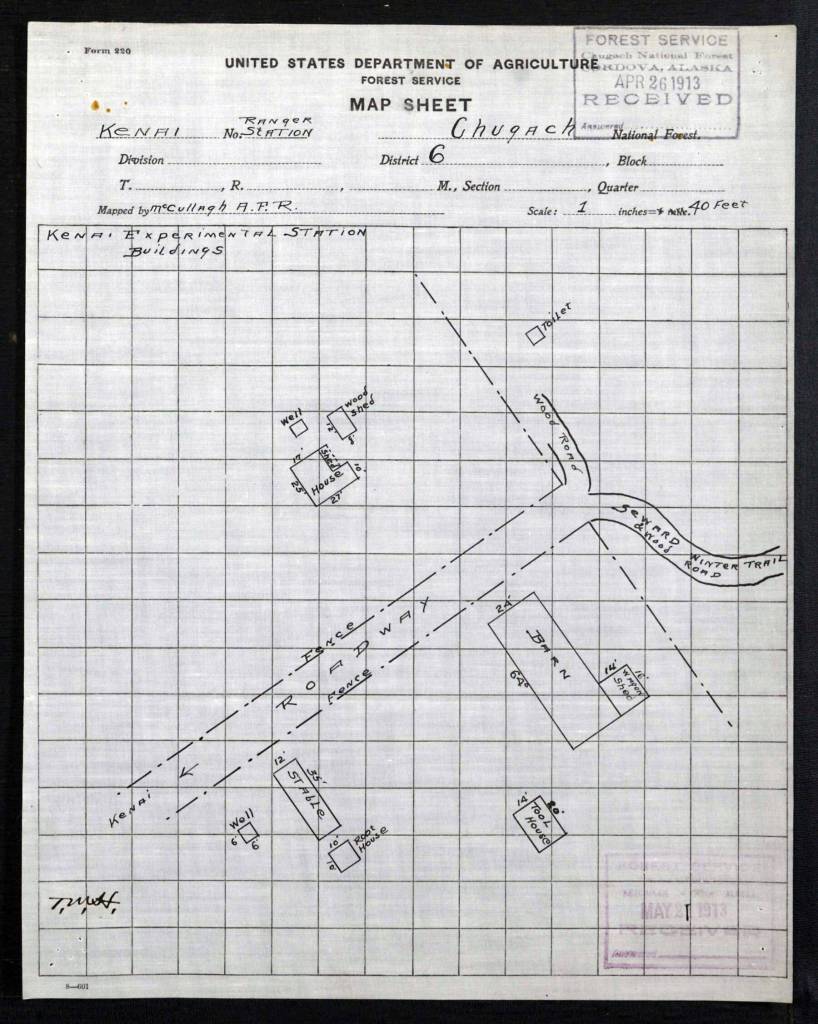

In late September 1912, forest ranger L. Keith McCullagh recommended to his supervisor, Thomas M. Hunt, that the Forest Service request from Georgeson the right to use the station house for a ranger station office.

Hunt passed McCullagh’s suggestion up the chain of command to his own boss, Forest Supervisor William G. Weigle, in Juneau. Weigle initiated some research on the subject and instructed Hunt to advise McCullagh to exercise caution and restraint until he, Weigle, had all his bureaucratic ducks in a row.

In mid-November, Weigle wrote to Prof. Georgeson and carefully broached the subject: “I have found it necessary to have a Forest Ranger stationed at Kenai…. It was my intention to construct a small house at this place for his use, but … I learned that the house belonging to the Agricultural Experiment Station at Kenai was no longer being used by the Department of Agriculture [and] … had been turned over to the … the Bureau of Education.

“I recently inquired of Mr. Lopp relative to whether they were using the building or not,” Weigle continued, “and he informs me that they have no need of it; therefore, I would like to know whether you would kindly permit the Forest Service to use the building.”

Since it had become clear to him that the Bureau of Education had no use for the station house, Georgeson complied with Weigle’s wishes—with the proviso that the Forest Service be in charge of all station property and keep all of its buildings in good repair. He recommended that Brownlow, if he so desired, be allowed to use a portion of the station house, and that the Alaska Transfer Company be allowed to use the barn at least during the upcoming winter.

The occupancy of Frenchy Vian, on the other hand, bothered Georgeson immensely. At one point, in fact, Georgeson wrote to Weigle and asked him to “evict [Vian] forthwith. He has not an altogether enviable reputation.”

Despite Georgeson’s wishes, however, moving Frenchy off the premises proved more difficult than expected.

Hunt instructed McCullagh to approach the Vian problem with common sense: “In case Mr. Vian has any reasonable claim either to compensation for caring for the property, or for continued occupancy of any of the buildings, the matter should be reported at once to [Weigle] without quibbling or promise on your part, as Mr. Vian probably dealt with Mr. Lopp in the matter.”

McCullagh, who could be diplomatic at times, tried to temper his sometimes brusque demeanor. But when he came through Kenai on patrol in late March 1913, he attempted to take possession of the station house and found it locked.

“Applied to Gov. School teachers [the Dolan sisters, who were friends with Frenchy] for keys to farm residence, at the same time reading [to them] my authority for making request,” he wrote in his diary on March 29. “They stated they did not have [the keys] and that anyway they intended using the farm kitchen for a domestic science kitchen for the summer. I told them I was sorry to inconvenience them, but under my instructions … I was compelled to take immediate possession of the premises as they were unoccupied by anyone.”

The sisters informed McCullagh that “Mr. Vian” had personal property in the house and warned that he would “get into trouble” if he continued his attempt to take possession. “I told them that we would see about that later,” he wrote. Meanwhile, he went looking for another source of keys to the building.

He finally located renowned hunting guide Andrew Berg, who had a key and granted him entrance. “We found a great deal of stuff which is supposed to belong to Mr. Vian, and it did not seem practical to move in with his effects still there,” McCullagh said. “As [the vacationing] Mr. Vian is expected in a few days, I decided to wait for him….

“I posted a formal notice on the door of the farmhouse, taking possession of it and all outbuildings, grounds, and everything connected with the Experiment Station and placed a Forest Service Yale lock on the door and nailed the windows.”

As one might suppose, this move was unpopular with the teachers.

The next day, McCullagh began hauling armloads of logs to the station’s woodshed, noting in the meantime that Frenchy had already accumulated a large load of firewood there. That evening, George W. Kuppler, husband of one of the teachers, walked over to the station house and posted his own sign next to McCullagh’s formal notice.

Kuppler’s sign, McCullagh wrote in his diary, “stated that anyone (meaning me) who entered the dwelling would be prosecuted to the full extent of the law.” Angrily, McCullagh strode over to the teachers’ quarters to confront the problem. The teachers were not at home, however, so he confronted George Kuppler, who was a practitioner of the law.

He told Kuppler that he planned to remove Kuppler’s sign.

Kuppler responded by becoming “highly excited,” McCullagh said, “and questioned my authority. In addition, he said that if I persisted in taking possession of the building, I might just as well apply for a transfer as he would make it too hot for me in Kenai.”

McCullagh laughed at him and told him that “what action they proposed to take was none of my affair … I did not see that the teachers had authority to do anything in the matter in as much as Mr. Lopp had given up the premises.”

He sent his assistant to the farmhouse the next day to remove Kuppler’s warning. He then wrote a relatively polite letter to the teachers explaining his actions and reasserting his authority, and a second letter to Hunt, covering much the same ground.

In the end, Frenchy Vian returned to Kenai and emptied the station house of his possessions with no further fuss. Afterwards, the question for Prof. Georgeson remained: What was to be done with the Kenai Station?

TO BE CONTINUED….