King Thurman: An abbreviated life — Part 6

Published 9:30 pm Wednesday, November 5, 2025

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The fate of King David Thurman, a Cooper Landing-area resident, had finally been learned in February and March 1915. Reports of his death became exaggerated over time.

The official investigation of the death of King David Thurman was considered complete when James Kalles, guardian of Thurman’s estate, sent a report of the investigation to the U.S. commissioner in Seward on March 12, 1915.

According to the report, Thurman had been attacked and grievously injured by a brown bear near his remote cabin on the Chickaloon River flats and had then managed to return to his cabin, where he realized that no one knew where he was and he had no chance to walk out on his own. Rather than continue to suffer, he put his Colt revolver to his left temple and pulled the trigger.

Because Thurman’s remains had likely been in the cabin throughout the end of the summer of 1914, the full autumn and most of the winter, they were gruesome to behold. The investigators — Kalles and two witnesses — decided, rather than attempt to remove the remains and bury them, to transform the small cabin into a funeral pyre.

But the story didn’t really end there.

Investigators could tell that someone had visited Thurman’s cabin between the initial discovery of the remains on Feb. 27 and the official investigation more than a week later. One member of the investigating team, Jack Rowell, had helped find the body and believed that someone had come to the cabin after his initial visit and had disturbed a few items on Thurman’s table.

He was correct.

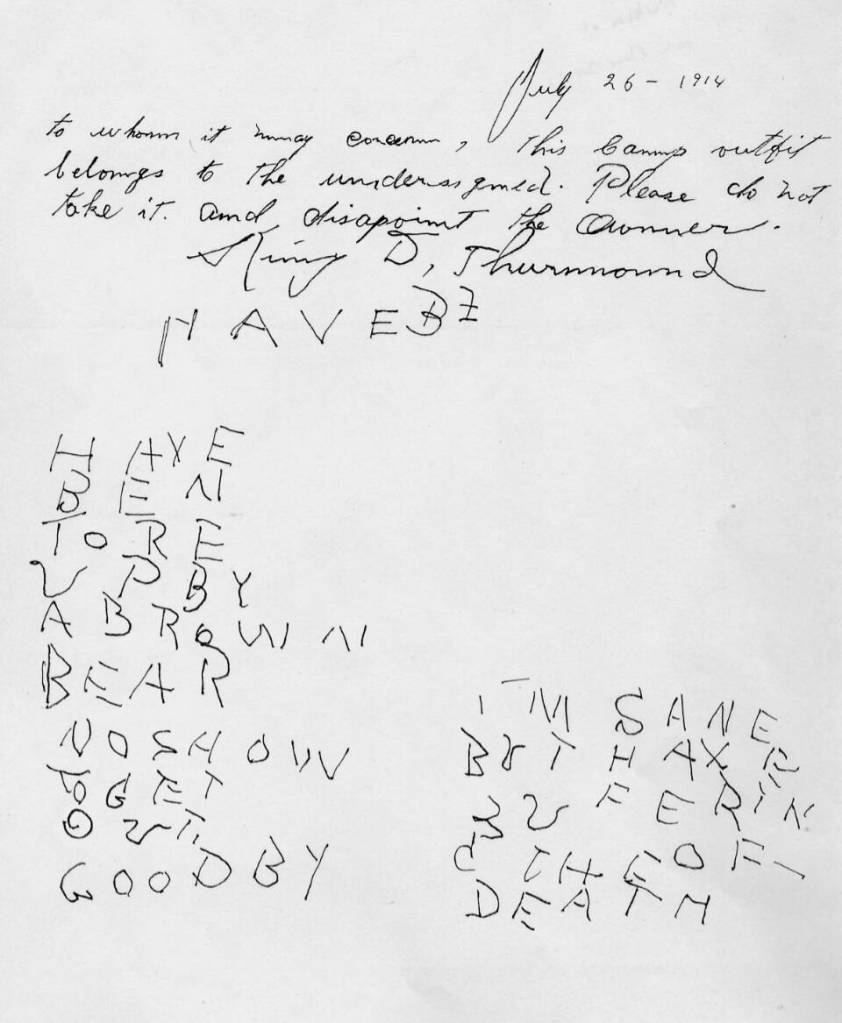

That “someone” had been Kenai’s William Austin and John Wik, who had removed Thurman’s final, explanatory message — essentially, his suicide note — and probably the final pages of his diary.

Difficult to read, as the message was likely written with Thurman’s non-dominant hand and in a weakened state, his last words were scrawled in all caps descending the left side of the page and then completed in the lower right-hand corner. The message has usually been deciphered this way:

“HAVE BEN TORE UP BY A BROWN BEAR. NO SHOW TO GET OUT. GOOD-BY. I’M SANE BUT SUFERIN [?] THE OF—DEATH.”

A few days after the cremation, Austin arrived in Seward and revealed the paper containing Thurman’s final note. For the next month, newspapers all over Alaska and in various parts of the Lower 48 produced — mostly faithfully — the contents of the note and appeared to tie up the loose ends of the miner’s final, fateful hours.

But sometimes a good story takes on a life of its own, and it didn’t take long before certain elements of this tale began to diverge from the facts — incrementally at first, then whole-hog.

The Story Changes

The August 1916 issue of Field & Stream magazine contained a Daniel J. Singer article entitled “The Giant Bears of the North,” which misidentified the first man to find Thurman’s remains as Jack Rolls. Singer stated matter-of-factly that Thurman’s final resting place had been constructed in secret so he could work “a rich gold claim nearby.” He also reported Thurman’s suicide weapon to have been a .22-caliber revolver, not the Colt .45 Peacemaker that Thurman was known to carry.

In 1918, Hugh H. Bennett, first chief of the federal Soil Conservation Service, wrote that Thurman had left the Cooper Landing area in the fall, as opposed to his actual departure date in mid-summer.

A decade later, Edison Marshall’s article — “Will a Bear Attack a Man?” — in the November 1928 issue of Field & Stream reported incorrectly that one of Thurman’s arms “had been jerked out at the socket.” Just before he died, said Marshall, Thurman managed to scratch out a single word, “bear,” which enabled those who discovered his body to “back-trail …. [and] … piece out the details of this woodland tragedy.”

Thurman, he asserted, had neglected his gun in his cabin when he carried a bucket down to the nearby spring to collect some water. In this pursuit, a “she bear” had met and attacked him. Marshall then added, with what appears to have been unintentional irony: “This tale can easily be verified in Seward, Alaska.”

Certainly the worst stretcher of the truth in this case was the renowned outdoor adventurer and writer John Whittemore Eddy, whose account in the 1930 book Hunting the Alaska Brown Bear often veered wide of the facts and indulged in wild, impossible-to-prove speculation. Unfortunately, Eddy’s sterling reputation led decades of future writers and researchers to simply accept his version of the story as gospel — and therefore to repeat it.

The errors and guesswork in Eddy’s story about Thurman’s mauling and death were myriad. They included these mistruths:

Thurman lived alone on Lost Lake. He left his cabin in the autumn of 1915 to purchase supplies in Seward for the upcoming winter trapping season.

On his way to Seward, he met up with big-game guide Ben Swesey and told him of his regret for failing to kill a bear near one of his mining or trapping cabins. He had a “queer feeling,” he told Swesey, that that bear might prove dangerous to him later on.

Thurman told friends and acquaintances that he wouldn’t be out of the backcountry until Christmas.

Just after New Year’s Day 1916, two trappers remarked to each other that they hadn’t seen Thurman in a while and thought they should go check on him. After discovering his remains, one of them hurried to Seward to report the death.

The U.S. commissioner swore out coroner’s jury, which, along with the commissioner himself, headed for Lost Lake. In Thurman’s cabin, they found his diary and suicide message. They also took detailed notes concerning the state of Thurman’s body: “His face had been torn off.” One hand was “terribly mangled.” His right arm and leg were broken, as were his collar bone, shoulder and several ribs. He had crawled back to the cabin while “holding his entrails with his good hand.”

Eddy plainly stated how the mauling occurred: the full water bucket, the sound of a step behind him, the “whirl” and speed of the surprise attack.

Eddy revealed Thurman’s thoughts after the attack: “He realized that it was all so hopeless. Nothing, not even the best doctor in the world, could save him.”

“His notes told that it was the same bear that he has passed up the month before, the bear he had told Ben Sweazy [sic] about.”

“The pain was more than he could stand. The last few pages were names of towns and people, his home down in west Tennessee…. Then … he told that he was going to shoot himself to get away from the pain. With a plea that God and his friends would forgive him, he … ended it all.”

Eddy wrote that he had gained his information from “one of the boys who made the trip as a member of the jury.” Of course, there was no such coroner’s jury. The commissioner had decided against forming one.

Fortunately for readers of outdoor tales and of history, Larry Kaniut, author, in 1983, of Alaska Bear Tales, adhered much closer to the truth and generally set the record straight about the death of King David Thurman.

It is easy to jump to conclusions. Even the most careful writers can be guilty of such leaps. But Kaniut, at least, did his homework.

The story of King Thurman’s short life and violent death contained plenty of drama. No exaggeration was necessary.