For writers, books don’t appear whole out of thin air. Instead, like orca whales sliding underwater, they can be elusive, works in progress until some event causes the creative idea to surface.

Covering a period of 25 years from Eva Saulitis’ first encounter with killer whales to a decades-long study of the whales of Prince William Sound and the Gulf of Alaska, the writing of “Into Great Silence,” published in January by Beacon Press, Boston, had to take its own time. Saulitis, almost 50, credits a diagnosis of breast cancer three years ago. She’s now cancer free.

“When I got the diagnosis, I asked myself, ‘If you only had five years left, what would you regret not doing? What would you regret not finishing?’” she said. “The number one thing that came into my head is, ‘You’ve got to write this book.’ It felt like an obligation. It felt like a responsibility to the animals in Prince William Sound.”

Saulitis reads and discusses her book at 5 p.m. Sunday at Bunnell Street Arts Center in a presentation sponsored by Cook Inletkeeper to commemorate the 24th anniversary of the March 24, 1989, Exxon Valdez oil spill.

Joining her is Sara Loewen, one of Saulitis’ students from the University of Alaska Anchorage master of fine arts low-residency creative writing program. Loewen, from a Kodiak fishing family, reads from “Gaining Daylight,” a memoir of what it means to balance lives on two islands. Books will be available for sale and signing.

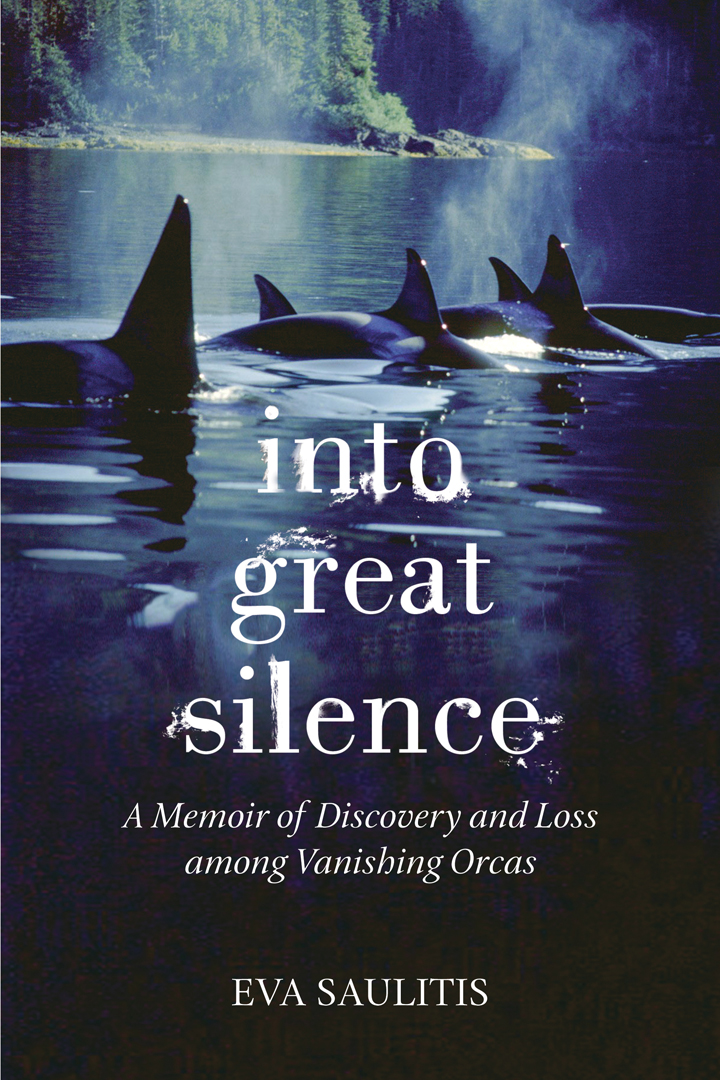

Subtitled “A Memoir of Discovery and Loss among Vanishing Orcas,” “Into Great Silence” holds within the memoir of a woman’s growth as a scientist and writer another story, that of the decline of a group of transient orca whales from 22 before the spill to just seven today.

While cancer motivated her to write the book, Saulitis said there’s another aspect to its timing.

Using the decline of a group of orcas as its focus, “Into Great Silence” examines the larger theme of extinction. It’s an issue not only of a small tribe of animals, but of species likely to vanish with climate change. Critical response and comments to her book have told her now was the right time to publish “Into Great Silence,” Saulitis said.

“We’re looking at issues of climate change — the idea of extinction, facing the potential for losing more and more species,” she said. “This is the time when the story needed to be told. … I wanted to personalize extinction.”

Coming to Alaska at 23 after graduating from college, Saulitis first saw orcas while working at a fish hatchery in Prince William Sound. Over the years she came to work with Homer whale researcher Craig Matkin, now her partner in life as well as science. “Into Great Silence” fits in that classic Alaska genre going back to John Muir: the story of a naturalist doing the detailed work of science. A poet and essayist as well as a scientist, Saulitis takes a creative nonfiction approach to her memoir. Her scientist friends have appreciated that, she said.

“Which is gratifying, because that’s not the language they use to talk about science,” she said. “That’s been reassuring, to

know the book worked for them as well.”

For decades, Matkin, Saulitis and others have been studying the resident and transient orcas of Prince William Sounds. The resident orcas, the fish eaters, generally stay in the area, eating silver and king salmon. The transient orcas, the marine mammal eaters, range farther. In particular, she writes of one group, the AT1 transient population, which she calls the Chugach transients, using informal names like “Eyak” and “Marie,” rather than the scientific labels of AT1 and AT2. The Chugach transients have their own language, their own peculiar clicks and sounds and their own ways of hunting. In effect, they are the whale equivalent of a culture or tribe — a tribe, like the Eyak language and culture, doomed for extinction.

Of the 22 whales documented before the 1980 Exxon Valdez spill, only seven survive. Nine of the Chugach transients disappeared over the winter after the spill. In one chilling historic photograph taken a day after the grounding of the Exxon Valdez, a group of orcas swim by the tanker as it spews oil into the ocean — a group Matkin identified as led by Kaj, a mature female that died in 1990.

With only 22 whales in the group, and lacking the genetic diversity to survive, the Chugach transients eventually

would have died out, Saulitis said, but the oil spill sped up that process.

“The spill is one of the causal pieces that led to the accelerated decline of these whales,” she said.

Feeding on harbor seals, Saulitis and Matkin put forth the theory that eating prey contaminated by the oil poisoned the orcas. Most of the book follows the slow, body-by-body decline of the group. It’s a somber, but necessary, story to tell, Saulitis said.

Some people have said they don’t want to read the book because it’s so depressing.

“‘It’s so painful, I’m not looking at it,’” people have told her, Saulitis said.

“It’s how we turn away from people who are suffering in our communities,” she added. “Do we turn away because it’s too painful? It’s not too painful. We think it is, but it’s not.”

At the same time, though, there’s hope. Returning to the sound, Saulitis said she still hears birds singing, still sees otters feeding on crabs.

“It’s right in your face, all of that is still there, very very brutal,” she said. “At the same time you’re aware in your head that things are being lost, are changing — at the same time, being aware of what’s worth saving, what’s worth advocating for … That’s what I hope the reader will come away with, what we still have, and what we still have to lose.”

Michael Armstrong can be reached at michael.

armstrong@homernews.com.