Editor’s note: Some of the language in this article may be graphic to some readers.

The state licensing board is investigating a complaint against the former head of South Peninsula Hospital’s rehabilitation department, who was placed on leave last December during a hospital investigation, but has returned to work as a therapist.

Douglas Westphal is accused by the complainant of telling the patient to double up on her pain medication, change into loose shorts and then running his hand up under the shorts and stopping just short of her vagina during a physical therapy session in 2009.

The patient, Lora Wilke, came forward in October 2017 as the nation reckoned with the #MeToo movement, in which victims of sexual abuse and harassment in the workplace joined a chorus on social media to tell their stories.

When Wilke read the stories, one thought struck her, she said. She may not have been the only victim.

In fact, six other women who worked for Westphal have also come forward, accusing him of sexual harassment, workplace harassment and bullying.

The women described their boss’s inappropriate comments and unwanted touching.

Wilke, a registered nurse at the hospital who was also Westphal’s patient, reported to the Homer Police Department that Westphal touched her in an inappropriate and sexual nature during the therapy session. The department investigated but is not pressing charges, according to the police report.

Four of the women who spoke to the Homer News have made official complaints to the hospital. The earliest complaint was made to the human resources department in August 2017. Three of the seven women have also sent grievances to their union representative with General Teamsters Local 959.

Westphal, who has worked for the rehabilitation department since 1993, has been a manager since 1994 and director since 2009, was placed on six weeks of administrative leave in December 2017 during a hospital investigation, confirmed Derotha Ferraro, director of public relations and marketing for the hospital. His leave began a few days after one of the women aired her concerns to other hospital staff, including the chief nursing officer at the time.

The hospital’s investigation has ended, and Westphal returned to work as a therapist seeing patients on Jan. 16, according to Ferraro. He is no longer head of the department, she said.

Physical therapist Karen Northrop was named interim director of the department, which provides physical, occupational, speech, hand and pediatric therapy. Ferraro said she could not comment on any plans to secure a permanent department head.

“As a senior lead therapist in the department, part of Karen Northrop’s responsibilities are to automatically serve as acting manager in Douglas’ absence regardless of the reason (varied schedules, staggered shifts, vacations, leaves of absence),” Ferraro said in an email.

Westphal did not deny the women’s allegations in a statement sent to the Homer News but said he was “surprised and saddened by these reports and accusations.”

“I respect the fact that these women feel that my words and actions amount to sexual harassment and bullying,” Westphal wrote in a statement he provided to the Homer News in February. “I feel that while my actions and words were never meant to be malicious or egregious, there is much I can and will do to improve my communications with staff, coworkers and patients.”

Not all of Westphal’s employees had problems with him. Five members of the rehabilitation department — Northrop, Emilie Otis, Bernadette Arsenault, Jackie Forrester and Krista Selan — read letters in support of Westphal and his abilities as a manager at a Dec. 20, 2017 hospital board of directors meeting, according to that meeting’s minutes. Board meetings are open to the public and minutes from the meetings are posted online. The Homer News requested copies of these letters from the hospital and was denied on the basis that the hospital could not release personnel information.

Three of those letters — from Northrop, Otis and Selan — were later sent to the Homer News. Four other former South Peninsula Hospital employees, and one current one, later sent unsolicited letters in support of Westphal to the Homer News.

After their original letters of support were sent to the Homer News, Otis and Northrop both sent follow up letters again speaking in support of Westphal, his managing abilities, and the positive atmosphere they say he created in the department. They and another member of the department who had sent an unsolicited letter to the Homer News, Susan Darr, said that as they expanded their families or watched other therapists do so, they never experienced issues with unfair treatment.

But allegations of inappropriate conduct by Westphal stretch back to 2009, when Wilke says he touched her inappropriately during a therapy session.

Lora Wilke

A Bellingham resident, Wilke began working at the hospital in 2005, and she knew Westphal as a colleague and mentor. He had played a part in her initial training as a new hire.

She was assigned to him for physical therapy in 2009 after undergoing knee surgery. Wilke, now 62, said that after their initial session, Westphal asked her to double her dose of Vicodin, an opioid pain medication, before coming in for her second session. Wilke said that while it was common for her doctor to prescribe one to two pills every “x” number of hours, the request to take two right before her therapy session made her uncomfortable, but she complied.

When she arrived at the rehabilitation department, Westphal asked her to don a pair of loose-fitting shorts, which she did. Westphal directed her to a private room and closed the curtain. Once there, Wilke said he began moving his hand up her leg, under the shorts. His hand ended up nearly touching her vagina.

“I don’t know what he was going to do,” she said.

Wilke said she doesn’t remember exactly how she pushed Westphal away, but that she did. The session continued, and she also later continued her scheduled therapy with him, although she said she felt immediately that she had been assaulted. Wilke said she didn’t report the incident at the time because she had other personal matters going on in her life that took precedence.

Asking patients to take pain medication, having them wear loose-fitting shorts and using a private room for initial sessions were, at the time, part of the standard practice of treatment for a patient who has had knee surgery, according to a letter circulated through the rehab department in December 2017. The letter was sent to the Homer News by Sarah Bollwitt, one of the women who spoke to the Homer News when Westphal was put on leave. The letter states that using a curtained booth for an initial PT evaluation is also current practice.

South Peninsula Hospital declined to confirm the standard practices for treating a post-operative knee surgery patient.

“The American Physical Therapy Guide to Physical Therapist Practice is the preferred source for information regarding treatment that the department relies on,” Ferraro wrote in an email.

American Physical Therapy Association spokesman Eric Robertson spoke with the Homer News about standards of practice for treating a post-operative knee surgery patient. He’s a board-certified clinical specialist in orthopedic physical therapy.

Robertson said that standards of practice for post-operative knee care can change slightly depending on the specific patient and what kind of surgery they had. Someone at risk for swelling or blot clots, for example, might be asked to wear compression hose, while a teenager who tore their ACL might not, he said.

When it comes to interacting with patients and their pain medications, Robertson said a therapist can ask a patient to take a dose closer to a session in order to provide increased coverage for pain.

“It is standard to sometimes time standard dosage with physical therapy sessions,” he said.

A therapist should never, however, change or adjust the overall prescribed dosage the patient was given, he said. If the patient was prescribed to take pain medication three times a day, for example, they should continue to only take it three times a day.

Hand placement, on the other hand, is “incredibly hard to standardize,” Robertson said.

“What is standard is to evaluate the joint that you’re treating and evaluate the joint above that and the joint below that,” he said.

For example, he said that if he were treating a patient’s knee, he would touch and palpate all around the knee. If it were someone’s hip, Robertson said touching “all around” it is more complicated. What is standard is for therapists to get permission to touch certain areas that may be sensitive while they interact with their patients, he said.

Inspired by the national #MeToo movement and statistics she had read on sexual abuse, Wilke reported the 2009 incident to the Homer Police Department in October 2017.

“And that struck me,” she said of the statistics she read. “It just hit me in my gut because I realized that not only had I been assaulted, but that I left the door open for many other women to encounter this man. That’s what set me off and that’s what continues to motivate me to this day.”

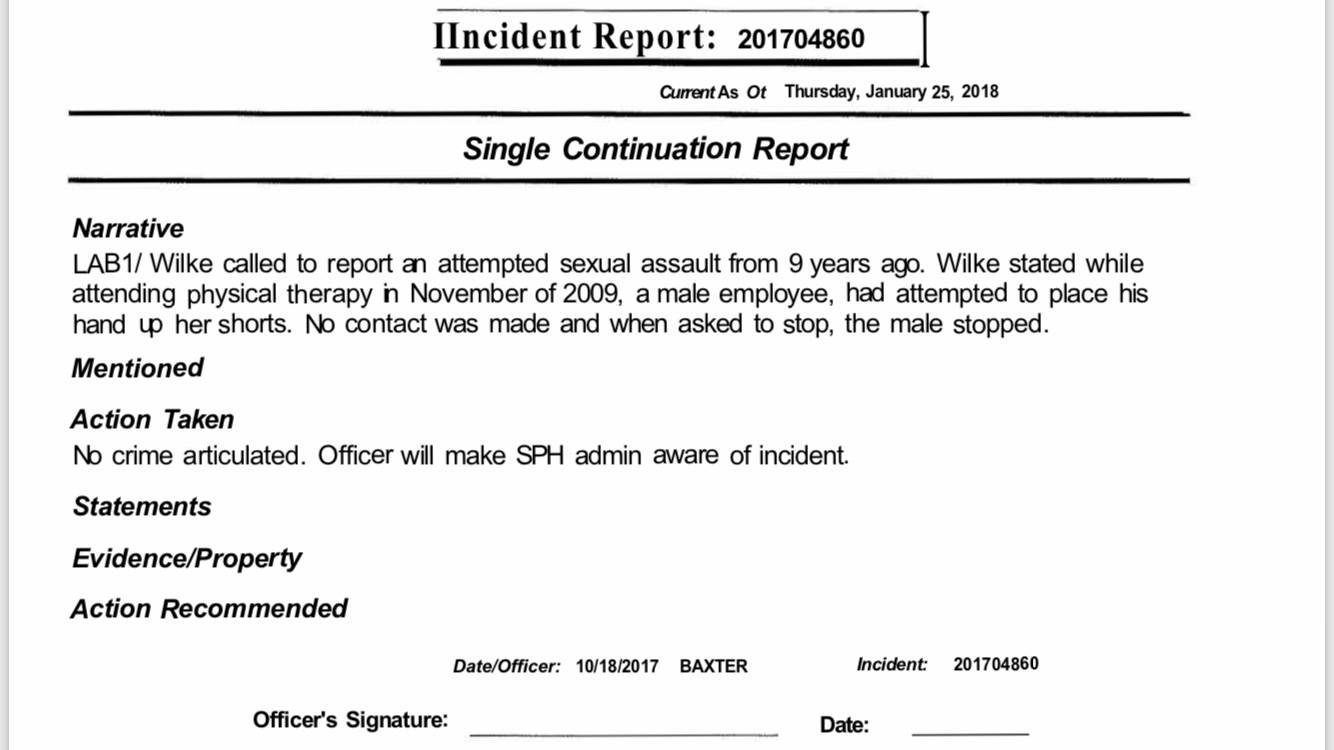

Sgt. Larry Baxter investigated and determined that no crime had been committed, according to the incident report.

“No contact was made and when asked to stop, the male stopped,” the report states.

Baxter later explained to the Homer News that, in Wilke’s case, “no contact” meant that no sexual contact was made. In other words, Wilke told the police department that Westphal’s hand stopped just short of her underwear, meaning that he did not make physical contact with her genitalia.

“The events she described didn’t statutorily meet the requirements for a sexual assault, or any crime really,” Baxter said.

In Alaska statute, sexual assault in any degree will include either sexual penetration or sexual contact.

“Every species of sexual assault, in order for it to be a crime, it is always going to require that the perpetrator commit sexual contact or sexual penetration,” said public defender Andy Pevehouse, who works for Alaska’s Third Judicial District, which includes Homer.

According to Alaska Statute definitions, “sexual contact” means that a defendant knowingly touched a victim’s genitals, anus, or female breast, or caused the victim to touch their own or the defendant’s. This can either be direct contact or through clothing, according to the definition.

In Alaska, sexual harassment is not a legal crime, though harassment is. Harassment in the second degree is defined in Alaska statute as including, among other actions, subjecting “another person to offensive physical contact.”

Baxter said that, based on what Wilke told him, the police department could have potentially forwarded charges of harassment for Westphal’s action of sliding his hand up her leg.

The statute of limitations on a Class B misdemeanor, which harassment is in Alaska, is five years. Since the incident Wilke described is alleged to have happened in 2009, Baxter said the police department could no longer press charges of harassment when she reported it.

“We see a lot of delays in reporting, especially like in this case, (and) it can really hinder the case because so much time has passed,” Baxter said.

Pevehouse said while there is no crime of sexual harassment in Alaska, people are able to file a civil suit claiming sexual harassment.

Wilke left South Peninsula Hospital in 2010, and later moved to Washington, where she lives today. Her friend, Kathy Smith, who still lives in Homer, confirmed that Wilke told her about the incident during the therapy session before she moved out of state.

“She didn’t go into great detail, but she was obviously shocked, you know?” Smith said.

Wilke said there were other reasons for moving but that the therapy session contributed to her wanting to leave.

“I was never the same after that,” she said. “I was just never the same.”

Police forwarded Wilke’s report to the hospital, but Wilke said she’s been disappointed by the hospital’s lack of adequate response. She made a report to the Human Resources or HR department herself by phone on Nov. 10, 2017. She also received written communication from the hospital’s risk management nurse on Nov. 27, 2017, and responded on Dec. 28, 2017. In her response, Wilke asked several questions about Westphal’s investigation. The response she got from the risk management nurse on Jan. 2, 2018, was that the hospital had nothing further to add.

She said part of the problem may be the hospital’s frequent changes to administrative staff and physical therapists.

“This management is like a revolving door,” she said.

Wilke said she has asked a Teamsters representative whether it would be appropriate for her to submit an after-the-fact grievance, but she has not heard back.

Sarah Bollwitt

An occupational therapist since 2009, Sarah Bollwitt came to Homer and the hospital’s rehab department in April 2015 as a traveling therapist. She joined the staff full time in October that same year.

Bollwitt said she started keeping a log of Westphal’s inappropriate behavior in June 2015, a few months after she started work. She detailed those incidents in a statement, which she sent to the Homer News. She made a complaint to the hospital’s chief nursing officer on Dec. 4, 2017.

Westphal was put on administrative leave four days later.

Bollwitt said Westphal bullied, intimidated and sexually harassed her, beginning with her second day of employment as a traveling therapist, when she says Westphal said, “You really are much more attractive in person than your profile picture (on Facebook) would suggest.”

In October 2015, Bollwitt had a miscarriage and told Westphal she wouldn’t be able to keep her commitment to volunteer at a community health fair as she recovered. She didn’t mention the miscarriage, but it was on file with the hospital. According to Bollwitt’s statement in her union grievance, Westphal responded: “What were you thinking? Having sex without a condom?”

“This might be the most personally offensive thing he’s ever said to me,” she wrote in her report. “I felt singled out and disrespected on top of already being devastated with a miscarriage.”

Bollwitt also detailed times when she says Westphal commented on her physical appearance or the way she was dressed in such a way that she altered her appearance in the future to avoid attention from him. He also often discussed the employment and sick leave details of other therapists in front of Bollwitt and other members of the department, she said. Bollwitt said she viewed this as a violation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Bollwitt became pregnant with her daughter and told Westphal in June 2016. She was the third therapist in three months to let the department know they were pregnant.

Bollwitt described Westphal approaching her while she was working with an older, overweight female patient in the rehab gym area. Bollwitt said Westphal asked the woman, “Are you pregnant, too? Because everyone else around here is.”

Westphal continued to make comments about Bollwitt’s pregnant body, she said, such as “being large” or being “way out there,” which made her uncomfortable. She reported that on at least two occasions he asked her, “Do you ever move out of your desk? I walk by and you are always sitting here. Do you get up or do your patients come to you?”

After the birth of her daughter, Bollwitt said Westphal made inappropriate comments about her breastfeeding. He asked her whether all she did all day was pump, and made a joke about the department all knowing what her daughter was “doing back there” during Bollwitt’s breastfeeding breaks, she said. When Westphal made these comments, Bollwitt said he called them across the department’s busy gym area.

On one occasion, Bollwitt described speaking with Westphal about the fact that her daughter had recently gotten another tooth. While in the clinic, he responded, “Oh, is she biting your boobs now?” she said.

During a meeting in October 2017 during which Bollwitt and Westphal were discussing her job, she said he told her he suspected she didn’t really need the job since her husband was a commercial fisherman in the summer and that she was probably only keeping it for the insurance. Westphal also told Bollwitt she would probably “be pregnant any day now, too,” she said.

Bollwitt’s husband, Morgan Jones, confirmed that she told him about her experiences at work close to the time they happened. He said it seemed like she was coming home with something new almost every day.

Whitney Horner, a close friend of Bollwitt’s in Colorado, said Bollwitt began telling her about incidents at work almost immediately after she started working at the hospital as a traveling therapist.

“I think the disturbing part for me was that it started right from the get go,” Horner said.

Bollwitt met with the hospital’s HR department on Jan. 2 of this year and made an official complaint. She said she has never been notified about the status of her complaint or the investigation of Westphal.

The rehab department was told in early January that Westphal would be returning to work to complete interviews, Bollwitt said.

She put in a request to be transferred out of the rehabilitation department to work in home health, which she said was granted in February.

“I’m not going back into that clinic if he’s my supervisor,” she said in an earlier interview.

Bollwitt submitted a grievance and a complaint with the union on Jan. 9, she said. Since then, she said was contacted by the Teamsters once to confirm that she wanted to transfer out of the rehabilitation department. Other than that, Bollwitt said she’s not aware of any formal resolution regarding her grievance.

Lora Harroff

Now living in California, Lora Harroff was a traveling therapist who worked for the department from March to September 2017. When she first met Westphal, he brushed her hair off her shoulder and grabbed her name tag that was pinned to the collar of her dress shirt. She reported her experiences to Human Resources while she was still working in the hospital and had a facilitated meeting with him before she left.

Harroff said she stopped asking him questions as a new person integrating into the department because Westphal was difficult, and she felt like he turned each situation into a question of her competence and intelligence. She had been a physical therapist for five years when she arrived in Homer.

One of the more embarrassing incidents Harroff recalled was a situation in which she was working in her office with the door open and a male therapist was working with a student in the main gym area. They were looking at functional motion, such as a person’s ability to reach an arm behind their back.

Harroff said Westphal called across the gym, “I bet Lora could do a great squat.” When the male therapist asked why, Harroff said she heard Westphal reply, “Just look at the size of her glutes. Lora, come do a squat for us.”

Harroff said she tried to ignore Westphal but that he wouldn’t stop asking her to do the squat until she did it.

Both Harroff and Bollwitt recalled Westphal saying he didn’t know if he wanted to hire a physical therapist because she was pregnant. The women said they viewed this as workplace discrimination.

On another occasion, Harroff said Westphal noticed a short-sleeved blouse she was wearing. She said he approached her and said, “Oh, you look so cute with your arms all exposed like that.” Like Bollwitt, Harroff said she never wore that shirt to work again and changed her appearance in the future.

In August 2017, Harroff says Westphal interrupted a private session she was having with a patient in one of the rooms with a closed curtain. He entered the room and looked at Harroff and the patient without saying anything, she said. When Harroff asked why Westphal was there, she said he answered, “I was just thinking of you.” This interaction left both Harroff and her patient uncomfortable, she said.

“That was the limit, to me,” she said.

On that day, Aug. 3, 2017, Harroff brought a complaint to the hospital’s HR department, having become frustrated over the past months at Westphal’s continued comments about her appearance and his interruptions, she said. HR representatives asked Harroff what outcome she wanted, and she told them she wanted an apology, she said.

About three weeks later, the HR department facilitated a meeting between Westphal and Harroff, during which Harroff said Westphal did not take responsibility for his actions. In the meeting, Westphal said he never meant for his comments to make her uncomfortable, and said he was sorry that Harroff was so sensitive to them, she said.

“I have never been treated so poorly by a manager as I was during my time at South Peninsula Hospital,” Harroff wrote in a statement she sent to the Homer News. “Not only did Mr. Westphal treat myself and other female employees in a demeaning manner, the human resources response to my concerns was extremely slow and lacking.”

Harroff said she and Westphal had next to no interaction until the end of her contract with the hospital.

Three people close to Harroff confirmed that she told them about her experiences at the department while they were going on and how upset she was while she worked there.

Harroff also sent a statement to the local union representative in January. She did not send one initially because she was a contracted employee while she worked at the hospital. Only full time employees are able to join the union.

Amber Rogers

In an email to the Homer News, traveling therapist Amber Rogers wrote that Westphal made her time at the rehab department “total hell.” Rogers worked there from December 2013 to June 2014, and then as a permanent staff member from October 2014 to October 2016.

Rogers said inappropriate and bullying behavior from Westphal began when she became a permanent employee. She said that while she cannot remember many exact details, Rogers described Westphal as verbally abusive.

“There were constant mean comments, putting me down all the time,” she wrote in the letter. “(He) always made me feel like a horrible person and pretty much made my life total hell.”

Once she had to leave work early on a Monday because of pain after being in a minor car accident over the weekend driving back from Anchorage. Rogers said Westphal’s response was that she shouldn’t have been driving to Anchorage on a weekend. Westphal also accused her of faking a knee injury in February 2016 when it took longer than expected to heal, she said.

Rogers said she was sick or needed leave more than usual over the two years she worked at the hospital.

“But a lot of it has to do with the way Douglas treated me,” she wrote. “He made me physically, emotionally and mentally sick.”

Rogers said she left the hospital because of Westphal. Dealing with her working situation brought Rogers to a place where she needed to seek counseling, she said.

“He made me so depressed (I) was suicidal,” she wrote.

Rogers said she spoke with a union representative at one time, but did not file a grievance. She told representatives of the hospital about her complaints during her exit interview, she said.

Other allegations

Three women who were or are employed at South Peninsula Hospital spoke to the Homer News on the condition of anonymity, out of fear of negative repercussions for their jobs. They observed the following:

• Westphal routinely stood very close to female staff, but not to male staff.

• Westphal told one woman that he wished a camera that was no longer in use in a dressing room she used to change her clothes was still working. A male colleague confirmed that the woman told him about Westphal’s comment shortly after it happened.

• One of the women said she changed her appearance and behavior at work — like Bollwitt and Harroff — to avoid Westphal’s attention.

• Another woman said Westphal told her she had to limit her breaks to pump breast milk to two 15-minute breaks, and if it took longer, she would have to skip lunch.

• The second woman said Westphal also yelled at her in front of staff and patients about a mix-up in scheduling.

• A third woman said Westphal made an inappropriate comment about how she looked in her leggings.

• Several women said Westphal accused them and others of faking illnesses or injuries, and he didn’t approve time off in a timely manner.

Of the women who asked to remain anonymous, one made an official complaint to the hospital’s chief nursing officer at the time, who forwarded it HR on Dec. 19, 2017. That same woman did not file a grievance with the union.

Another anonymous woman did make a complaint to the union, but not to hospital HR. The third anonymous woman did not report to either.

Hospital’s response to the women

All seven women interviewed by the Homer News expressed disappointment, frustration and anger at a lackluster response from the hospital, especially the human resources department. Several of them mentioned high administrative staff turnover as a factor in that frustration.

Ferraro, the hospital’s public relations and marketing director, said the hospital takes accusations of harassment seriously.

“This is why we instituted a workplace bullying policy and council about 10 years ago,” she wrote in a statement provided to the Homer News in February.

The hospital’s bullying policy addresses:

• Verbal bullying: abusive or offensive remarks.

• Gesture bullying: Threatening glances or intimidating body language.

• Persistent and excessive singling out or monitoring

• Raising one’s voice at an individual in public or private

• Public humiliation

• Public reprimands

• Unwanted physical contact

• Refusing reasonable requests for leave

The hospital’s harassment policy states that the hospital does not allow harassment in employment based on changes in marital status, pregnancy or parenthood, among other factors. It describes sexual harassment as “unwanted sexual attention of a persistent or offensive nature made by a person who knows, or reasonably should know, that such attention is unwelcome.”

Sexual harassment in the form of sex discrimination has taken place, according to the policy, when an employee interferes with another employee’s work performance or “creates an intimidating, hostile or offensive work environment.”

In his statement to the Homer News, Westphal said he would like to think the allegations are not a reflection of his true nature. He is participating in education on harassment and bullying, the statement says.

The hospital requires annual training on harassment, according to Ferraro’s statement.

Hospital employees may report problems to the human resources department or to the Healthy Workplace Council, which reviews workplace bullying cases and acts as an advisory panel to hospital administration, according to its bylaws.

Permanent employees also may file grievances with their union representatives. The hospital also uses a Trauma Informed Care committee to identify areas of improvement to benefit employees and patients.

“I have absolute confidence in the hospital’s ability to conduct a fair investigation of these allegations and their ability to make a fair decision in regards to my employment,” Westphal said in his statement, which he sent to the Homer News after the hospital’s investigation and after he had returned to the department as a therapist.

Ferraro said in a February interview and in her written statement that she couldn’t comment specifically on the hospital’s investigation of Westphal.

Many of Westphal’s actions that women described are considered unacceptable conduct under the hospital’s code of conduct. They include:

• verbal abuse

• psychological abuse

• uncivil criticism

• criticism made in a non-private setting

An employee who violates the code of conduct and is reported can be investigated by the division manager, human resources manager and CEO, according to the policy.

The policy states action will be taken when subsequent reports of disruptive behavior are made against a person, and another investigation takes place. If “it appears that a pattern of disruptive conduct is developing, the Chief Executive Officer shall ensure that appropriate disciplinary action is initiated,” the policy states. Ultimately, a person may be terminated.

Ferraro said the majority of the hospital’s staff are protected by their union contracts, which she said have a very prescribed series of steps they would go through in this situation.

Employees in manager positions are on the “at-will” side of things, Ferraro said. They can be fired by the hospital for anything allowable under the law, she said.

In the hospital’s policy on harassment, the section on managers states that “managers who knowingly allow or tolerate harassment are in violation of this policy and subject to discipline.”

All of the hospital’s policies and education practices are under review by a lawyer routinely retained by the organization, Ferraro said. That review is taking place in light of the #MeToo movement but was prompted by the situation with Westphal, she said.

“Changes to the policies and practices will be made as appropriate once we complete the review, if necessary,” she wrote in her statement.

Other responses

The union for hospital employees, General Teamsters Local 959, has also had a hand in the fallout of the accusations against Westphal. President Barbara Huff Tuckness said the union cannot discuss the details of any grievance submitted on the subject, but did say the union has at least one grievance filed in regard to Westphal.

After a grievance is sent to the union, Tuckness said it is reviewed by a shop steward before the union submits it to, in this case, the hospital’s human resources department. From there, members of HR, a union representative and those involved in the case sit down to discuss the matter. The hospital would then respond to the union after that meeting, she said.

Tuckness said at this point in the process, the union either gets an agreement to settle the case, or the hospital would deny the grievance. From there, the case would move to arbitration through lawyers representing both sides.

The grievance Tuckness confirmed has been forwarded to the union’s legal department, Tuckness said.

For her part, Wilke has filed a complaint against Westphal’s professional license with the Alaska Division of Corporations, Business and Professional Licensing. That division investigates complaints on behalf of 43 boards or professions in Alaska, including physical and occupational therapy.

Chief Investigator Greg Francois confirmed that there is an active investigation involving Westphal’s license, but said he cannot comment on any details regarding an active investigation.

When someone makes a complaint against a professional license, Francois said the person making the complaint fills out and returns a packet. The case moves into the “complaint” phase, he said, in which it is reviewed by a member of the Board of Physical Therapy and Occupational Therapy. Then investigators begin to collect information including police records, witness interviews, financial documents, court records, etc.

“The Division collects information, statements, and any relevant records and materials, which are then evaluated by licensed professionals on the Board for adherence to licensing law, industry, and professional standards,” Francois wrote in an email. “When the Board finds evidence a provider does not meet these standards and represents a demonstrable public safety risk, the Board can take a number of actions.”

If a violation by a therapist is found, Francois said it moves into the “investigation” phase. The therapist, or licensee, is informed of the investigation. Investigators have time to collect more information, after which the board can recommend some kind of disciplinary action.

According to the division’s website, the Board takes disciplinary actions when the investigation unit has been able to prove a therapist has done any of the following:

• Practiced physical therapy/occupational therapy in a manner detrimental to the public health and welfare;

• Been negligent in practicing or assisting in the practice of physical therapy/occupational therapy;

• Obtained or attempted to obtain a license by fraud or deception;

• Failed to comply with the required continued education and license renewal requirements, or;

• Engaged in unprofessional conduct relating to federal or state laws or rules.

A therapist can reject the disciplinary action given by the board. If that happens, Francois said the investigative unit files an “accusation” against the therapist’s license. The therapist can request a hearing, and a decision from that hearing goes to the board with suggestions from both parties about what should happen to resolve the issue. The board can decide whether to accept that decision, deny it or modify it. The board also decides what kind of sanctions to put on the therapist’s license.

Westphal’s license, which was issued in 1989, has no actions taken against it, according to its license details in the division’s professional license registry. It also has no accusations against it currently, which means Wilke’s complaint against him has not yet reached that stage.

As Westphal takes additional training on harassment and bullying, the state’s Division of Corporations, Business and Professional Licensing continues its investigation into Wilke’s complaint against him and the local union is processing its grievance.

Homer News Editor Michael Armstrong received treatment from one of the unnamed sources at the hospital and from Sarah Bollwitt, before any allegations against Douglas Westphal came to light. He subsequently had two more occupational therapy sessions at the hospital with a therapist other than Bollwitt before ending treatment. He originally began interviews for the story but turned it over to Homer News reporter Megan Pacer to avoid any appearance of a conflict.