Editor’s note: This is the third in the Morris Communications series “The case for conserving the Kenai king salmon.”

There are very few things that can immediately quantify the declining value of sport fishing for Kenai River king salmon as quickly as the shelves at Trustworthy Hardware in Soldotna.

Shelves that once held Kwikfish K16 lures in 75 color combinations — tailor-made for fishing on the deep-swimming king salmon— are now crowded with sockeye and silver salmon gear. Newly crafted Kenai River king salmon fishing rods that generated excitement from guides after debuting with new actions and a low-price point sit in rows gathering dust.

“The guides got real cautious about buying and then of course people are just going to make do with what they have,” said Scott Miller, co-owner of the store. “If the fishing is not good they’re just not going to go out and buy rods. They’re going to buy fly rods or rods for silvers. … We’re selling more (king salmon rods) in Washington and Oregon now because they’re having a good run of kings.”

Nearly two years ago, just prior to the disastrous 2012 fishing season, Trustworthy hardware debuted the $300 TW Elite king salmon rod.

“We sold 200 of them before the season,” Miller said.

Now there are $30,000 worth of the rods in the $1.5 million in fishing tackle Miller said he carried over from last year’s lack of sales.

“It’s just the surety of fish,” he said. “We’ve been very lucky. We deal with the guys down in the Northwest a lot, we buy from them, we have other stores that we talk to down there and they’ve gone through this cycle for a long time where it’s up and down and they don’t know if they’re going to fish from one year to the next.”

And, while a king salmon pulled out of the river and flopping in the bottom of a boat does not have a fixed dollar amount attached to the time and effort it took to land, the economic impact is measurable in other, more nebulous ways.

Where it could once be measured in the number of luxurious fishing lodges and rental cabins lining the river, it can now be seen in “For Sale” signs piling up — six alone in front of lodges on Kenai’s Angler Drive.

Businessmen and visitors alike sounded the alarm in 2012 when the fishing season for king salmon was closed by emergency order before the season was officially over.

“You’ve got to go to the top, you’ve got to write your letters because I want my son — when his 18-year-old son graduates, my grandson graduates — I want to be able to say ‘Hey let me take you to the biggest king salmon in the world. Let’s go to the Kenai and let’s spend a few more thousand dollars to catch a king,” said David Burk, of Arlington, Texas, who described himself as an angler who spent $10,000 in 2012 to catch a king, only to see the late run season closed early and bring his trip to a premature close.

Steven Anderson, owner of the Soldotna Bed and Breakfast lodge, estimated at least $50,000 in losses during the unprecedented king salmon fishing closure in 2012.

“How much of that money would have gotten spent locally? The majority would go to guides. There’s lunches, fishing licenses, fish shipping boxes, welcome gifts that we supply, all that stuff,” Anderson said in an August 2012 Peninsula Clarion article. “That’s probably about $40,000 out of the $50,000. That’s what I can measure that I know we lost. But what about stuff that I can’t measure, that we’ll never know because those people never came?”

A booming guided fishing industry targeting the world-famous king salmon has become, for some, a series of cobbled together trips where would-be king anglers are instead taken out fishing for silvers, sockeye or halibut.

Businesses that once relied on the Kenai king salmon for a healthy percentage of yearly profits now find themselves diversifying to make up for the loss in revenue.

Sockeye salmon are Cook Inlet engine

While fishermen and business owners in Cook Inlet find it increasingly difficult to bank on a stable king salmon season, the potential for other fish to make up for the deficit is there.

The average king salmon fisherman spends more money in Miller’s store, but the sheer volume of sockeye salmon fishermen drives his business in the summer.

“When it comes to overall money, I think it always has been (sockeye salmon fishing),” he said. “There have always been more people, more money spent just because of the limits. You can go out and catch three fish every day so it keeps people here longer.”

The sockeye fishermen may not be spending the same amount of money per fish as the king salmon fisherman, but sheer volume can make up the deficit.

While Miller’s business can take a hit and diversify, others may not be as lucky.

“Talk to a guide or a lodge that’s on the river and obviously for a king salmon guide, that’s his business. This year, we’ve seen hundreds of guides that come in every day and say ‘Is there anybody to take out?” Miller said.

Guides that have been established in the region for decades are having to change the way they offer trips.

“Now are they going to make a living doing that? No. Because nobody is going to pay $200 to $300 to go sockeye fishing,” Miller said.

Joe Hanes, owner and operator of the Fish Magnet Guide service, said before the 2013 season that the closure to king fishing had been devastating to his business.

“When they close us, we lose our bookings for weeks,” he said. “When they reopen we can’t just call people and tell them to come back.”

Alex Douthit, owner and operator of Salmon Buster’s Guide Service said in an interview before the 2013 season that the king season being increasingly restricted made it harder to plan bookings.

Even planning trips for the last two weeks of July — the height of the late run of Kenai River king salmon — can be problematic.

In 2013, the river was restricted to catch and release and trophy fishing by July 23 and closed to king fishing entirely by July 26.

Miller said a king salmon guide would see fewer and fewer king salmon fishermen on the Kenai River in the coming years.

“It’s quite an investment, even if you’re a private fisherman. You’ve got to have a boat,” he said. “ You’re spending a ton of time out there and it’s not a meat fishery anymore. I think people are starting to look at it as just, more of a true sport fishery where you’re out there to hook and release.”

Although chinook, or king, salmon may be the most highly prized fish in Cook Inlet, that doesn’t mean they are the most valuable.

“We have 30,000 families that are participating in the personal use fishery, we have a very robust sport fishery that is taking half a million sockeye and a commercial fishery that targets them,” said Ken Tarbox, a retired research biologist for the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. “Our community is driven by sockeye and sockeye users now, guides are even switching to sockeye.”

While the downturn of king salmon in Cook Inlet has dominated public discussions of the fisheries, Tarbox does not believe the social and political focus will remain on the species indefinitely.

Rather, sockeye salmon, which are harvested by more fishermen, will begin to dominate the discussion again.

“I’m not making the argument that it’s commercial versus sport king fishing, I’m arguing that it’s sport and personal use sockeye fishermen that will drive sport chinook fishermen to the backburner,” he said.

The 2013 fishing season, Tarbox said, could be a harbinger of years to come.

Personal use fishermen who came to the Kenai River dipnet fishery in droves had a difficult year. Several blamed their unproductive fishing effort on the commercial fishing fleet whose boats were visible from the mouth of the river.

Tarbox said the backlash was loud.

“It was a good example of what a poor run might produce … the user group started to raise up,” Tarbox said. “A manager is foolish in my mind if he tries to ignore 30,000 household permits for personal use fishermen and a half a million sockeye caught in the sport fishery and thinks that chinook will come out on top.”

A rush to the Kenai Peninsula

Fishers, whether they be commercial, sport, personal use or subsistence, can agree that king salmon are an important piece of Alaska’s economy. Beyond that consensus, the specifics of how big a piece — are murky.

What is clear is that each year, the bulk of the sportfishing effort in Alaska is felt by Kenai Peninsula residents and a significant portion of that effort is spent on the Kenai River.

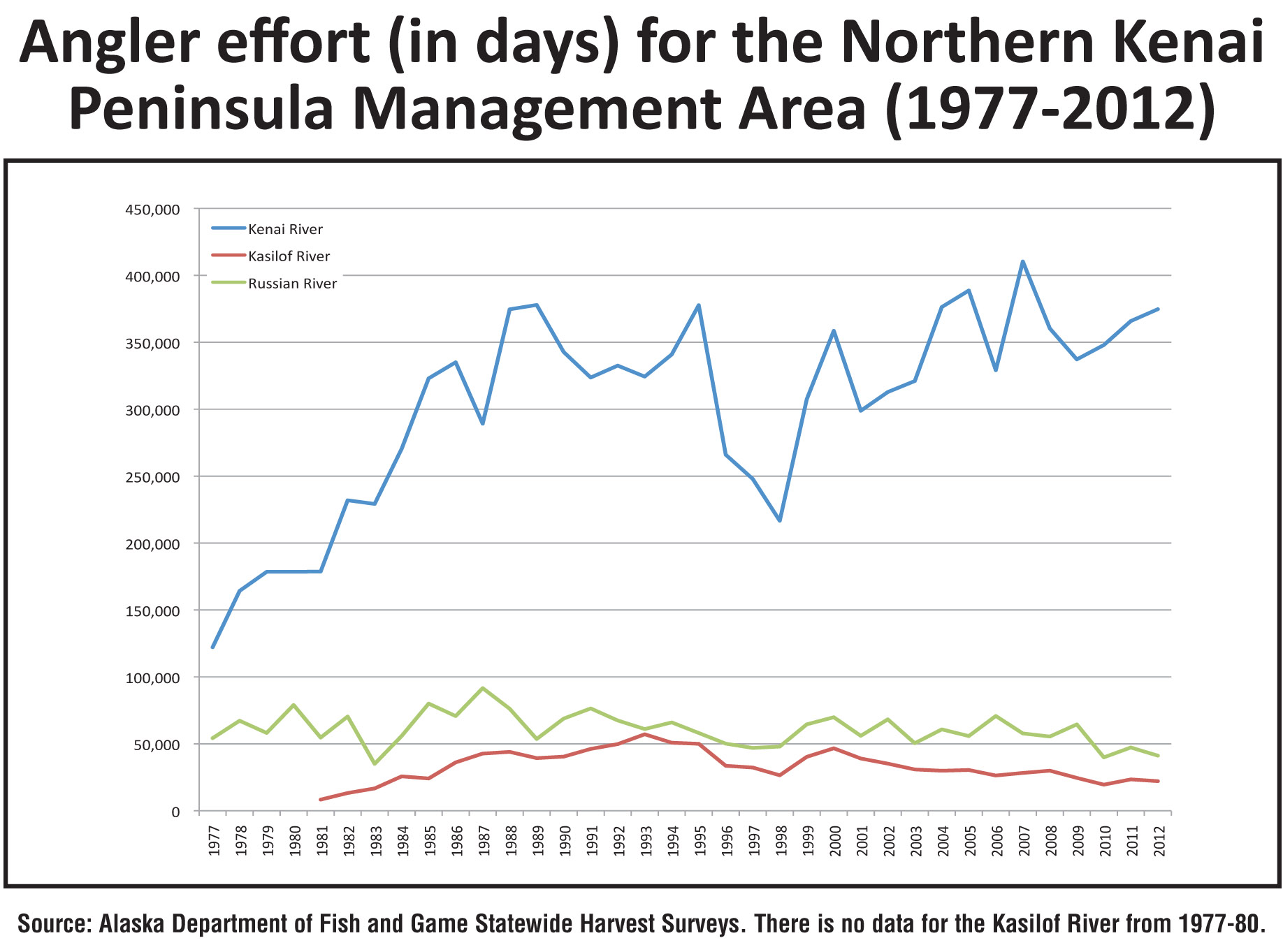

According to Alaska Department of Fish and Game data on angler days of effort expended by recreational

anglers, the Northern Kenai Peninsula Management Area containing the Kenai River saw nearly a quarter of all of the fishing effort in the state in 2012.

Of that, 82 percent of the angler days of effort — a measurement of the time spent fishing by any one person — were spent on the Kenai River.

A 2008 study by the Kenai River Sportfishing Association estimated that recreational salmon fishing in Upper Cook Inlet generated 3,400 average annual jobs producing more than $100 million in income annually.

While those numbers are certain to have changed in recent years due to natural fluctuations in the tourism industry caused by the national recession that dramatically reduced visitor traffic to Alaska, and the unpredictability of Kenai River king salmon fishery, Kenai River Sportfishing Association Executive Director Ricky Gease said the study was designed to be a convincing argument regardless of the numbers.

“The basic concept is that Cook Inlet is unique in the regions of Alaska in that the values of the non-commercial fisheries far outweigh the economic values of the commercial fisheries,” he said. “That’s unique in the state of Alaska, you don’t find that disparity anywhere else in the state.”

A recent report produced by Northern Economics for the Cook Inlet commercial fishing and processor advocacy group Alaska Salmon Alliance measured the ex-vessel, or dockside, value of the commercial fishery in Cook Inlet at $54 million in 2011 and $102 million in direct value to the area.

While there are other king runs in Upper Cook Inlet, the key to the Kenai River’s popularity lies, at least partially, in its accessibility, said Pat Shields, ADFG commercial area biologist.

“Literally, you can fly from, say, Miami, Florida, on a jet and land in Anchorage, get on a plane or a car and be down to the Kenai River on the same day that you left,” Shields, said. “The Kenai River has multiple access points with a run of large kings.”

People may be headed to Southcentral Alaska to fish, but they are not attempting to catch as many king salmon in recent years.

According to ADFG data on license and king salmon stamp sales from 2002 to 2011, the amount of revenue generated by those sales has dropped dramatically since its peak in 2006 when it topped out at 68,234 stamps sold, generating $1.2 million in revenue.

In 2011, just more than 48,000 king salmon stamps were sold, generating $846,000.

While that loss in revenue on the king fishing side can potentially be made up in other fisheries, it can be a hard sell to anglers who travel to the area for a chance at a

Kenai king.

Dave Blackley, owner of Caribou Run Alaska Fishing Adventures, said he guided dipnet fishing trips, sockeye and trout fishing trips — just about anything he could do to accommodate clients who wanted to catch king salmon — and still he lost a third of his bookings in 2012 when the Kenai king salmon season was closed early in July.

Several guides said they were no longer able to make a living off of guiding alone and had second jobs outside of the fishing industry.

Miller of Trustworthy Hardware thinks the uncertainty of seasons is what keeps fishermen from wanting to commit to a king salmon trip in the area.

“The second run, the predictions this year weren’t real good; that’s why they shut it down early,” he said of ADFG management of the Kenai River. “But they come out with those predictions so late and that’s part of the problem for businesses is that they, the department, waits so long to come out with them.”

In recent years, anglers expected a closure on the ailing early run of king salmon in May and June, but not the late run in July, Miller said. The early run in 2013 of less than 6,000 kings was the lowest on record and despite a total closure to sport fishing the minimum escapement goal for fish to reach the spawning grounds was not met. There is no commercial fishing on the early run of kings.

“It may not be the greatest run in the world for fish,” Miller said of the late run, “but we fish it and people buy. They come because it’s open and they can fish.

Weight of the decline

When commercial and sport fishermen are kept out of the water due to king conservation concerns, the effects are immediate: They stop buying goods and services from businesses set up to support the fishing industry.

One such business — fish processing — has seen a steady decline in the number of king salmon brought in to be cleaned, packaged and sent home with a successful angler.

For processers who charge by the pound, the loss of king revenue comes down to weight.

Sockeye, or red salmon, usually weigh about six pounds while kings are the largest of the Pacific salmon and typically weigh about 36 pounds, according to ADFG data.

“We’re checking in 15- to 20-pound fish instead of 60- to 80-pound fish,” said Lisa Hanson, owner of Custom Seafood Processors. “It has been a gradual decrease, I would say over the last five or six years.”

Soldotna’s Trustworthy Hardware store has been open for 27 years, before that it was Ellington’s and before that, it was Penn’s Hardware.

Miller grew up in Soldotna, watching the king salmon fishery evolve.

“I used to fish every day before ball practice down at Centennial (Park),” he said. “I could hook, as a kid, six or seven kings, land a couple every night,” he said. “The guys down there now, they’ve got better gear, they’re better fishermen. They can go weeks without catching a fish down there.”

For selling fishing merchandise, a struggling fishery can sometimes be seen in the volume of fishing tackle sold.

“The harder the fishing gets the more lures you sell because people want something different,” Miller said.

In the early 1990s, people would buy two or three colors of Kwikfish lures, he said.

“Silver, chartreuse and silver, and silver with a red tail,” Miller said. “Silver chartreuse was the most popular. People started asking for different colors … it built all the way up to maybe 2003-2004 when it peaked. “

Fishing was still open and people were getting desperate to catch them.

“You would have a guide come in and he would get six of this and six of that,” Miller said. “At one point we carried 75 colors of that one lure. This year, we carried 26 maybe. That’s just out of necessity for me to retract and go back to old numbers of what we were selling. “

So a fishery that once made up about 20 percent of Miller’s business has dropped to somewhere between 5 percent and 8 percent, he said.

Commercial vs. sport values

Perhaps no other economic question has been asked, answered and asked again in recent years than which group of fishermen in Cook Inlet bring in more money.

Commercial fishermen and sport fishermen have addressed it time and time again with the answer being dependent on which of the two user groups was speaking.

The uncertainty of the issue continues when a hodge-podge of data is released each year reporting on what people spent, how they spent it, who bought it, who sold it, who processed it and — above all — where did the money go?

In terms of hard numbers, commercial fishermen can rely on catches and prices to quantify the baseline economic impact of their fishery.

According to data from the National Marine Fisheries Service, from 2010 to 2011, three Cook Inlet ports — Seward, Homer and Kenai — are among the top 30 highest valued commercial fishery landings in the United States.

The estimated ex-vessel, or dockside, value of the 2013 commercial harvest in Upper Cook Inlet was $39 million, according to ADFG data.

Sockeye salmon were the most valuable commercially making up more than 75 percent of the ex-vessel value in Upper Cook Inlet since 1960, according to the ADFG 2013 post-season report.

Just more than 5,000 king salmon were harvested by all commercial users in Upper Cook Inlet, generating an ex-vessel value of about $180,000 or about 0.5 percent of the total commercial fishery, according to the report.

Despite the enormity of value to the region, Kenai Peninsula Borough residents only represented about 8 percent of gross earnings in Alaska’s fisheries, according to a presentation to the borough by fisheries economist Gunnar Knapp.

Sport fishing, by contrast, is harder to quantify and economic studies come with questions about methodology.

An economist charged with assigning value to the sport fishery might interview a tourist about the amount of money spent in the state but how does that amount get divided into categories like transportation, fuel, food and fishing.

“There are some judgment calls that have to be made,” Shields said. “When you get into those types of economic analysis … they come with a significant challenge.”

According to Kenai Peninsula Borough data from 2008, fishing guides had gross sales of about $60 million annually from 2003 to 2008.

By 2008, there were 435 registered guides and about 75 percent of them were residents, meaning the money they brought into the local economy stayed.

A 2007 Fish and Game study on the economic impacts and contributions of sportfishing estimated that anglers spent about $277 per day on fishing trips in Alaska.

But a direct comparison between the value of a sockeye salmon — the target for most commercial fishermen in Cook Inlet — and a chinook salmon is unclear.

Ricky Gease of the Kenai River Sportfishing Association said despite the inability to directly compare the value of the two fish, it was still clear that sportfishing and personal use fishing brought more money into Cook Inlet than commercial fishing.

Acknowledging the difficulty in making direct comparisons between the value of sport fishing and the value of commercial fishing in the inlet, Knapp wrote in 2012 that both were hugely important to the Cook Inlet economy.

Next week: A look at king salmon on the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers.

Clarion file material was used in this article. Rashah McChesney can be reached at rashah.mcchesney@peninsulaclarion.com. Comments on this article can also be sent to kenaikings@morris.com.