In Alaska art and culture, a spirit of irreverence often runs counter to serious or commercial images of Alaska. Done well, traditional Alaska art celebrates the state’s natural beauty and character of its people. When this celebration runs to excess — think painted gold pans or romanticized landscapes — artists and entertainers like Mr. Whitekeys stand ready to throttle back on an overly sentimental vision of Alaska.

That’s the idea of “Unalaskana,” a four-artist show at Bunnell Street Arts Center on exhibit through Sept. 4. Artists Rachel Mulvihill, Angela Ramirez, Duke Russell and Michael Walsh provide sometimes comical and always original views of Alaska subjects. They’ve created images of an Alaska “that’s true and gritty and must ultimately be embraced by those of us who live here,” said Bunnell director Asia Freeman at a talk at last Friday’s opening.

Freeman noted inspiration for “Unalaskana” from “Backyard Alaska,” an earlier and similar show she and Walsh did in March 2010 at the Pratt Museum. Like “Unalaskana,” the Pratt exhibit has the same mix of irony and respect. While “Unalaskana” challenges clichés, it still acknowledges the curious mix of interesting people living in a beautiful land.

The paintings of Fairbanks artist Rachel Mulvihill opened Freeman’s eyes to a new way of looking at Alaska, Freeman said. Mulvihill’s paintings are a double entendre, she said, an Interior artist painting interior landscapes. If the exterior is shown, it’s framed by windows or seen from a skewed angle, such as the front of a house and an icy walkway.

“I was caught off guard and intrigued by someone choosing to paint this image of Alaska,” Freeman said.

Mulvihill’s “Green Interior,” for example, shows an Alaska home in winter, with green house plants, green fruit in a still life on a table and green colored photos and paintings on the wall. The scene looks out on a snow covered grove of birch trees. In a bit of irony, in the painting of the room a traditional Alaska landscape hangs on the wall above modern Alaska Native art that could have been done by Homer artist Ron Senungetuk.

“A lot of my paintings are some sort of self consciousness, about exploring the place,” Mulvihill said in her artist’s talk at the opening. “I’ve spent most of my time indoors. To me, that’s my landscape, especially in winter.”

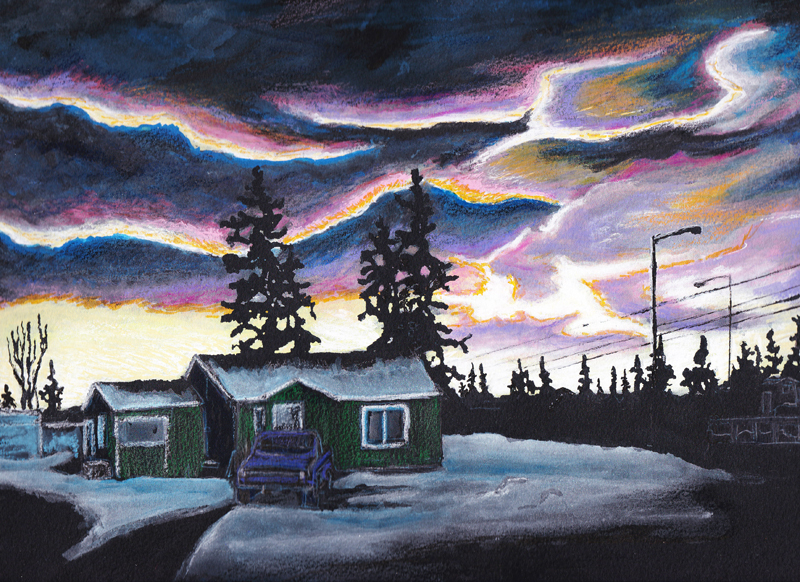

Anchorage artist Angela Ramirez also paints Alaska landscapes of a different perspective. Ramirez bicycles around Anchorage in her Spenard neighborhood and likes to chase sunsets, as she calls it.

Painted on black Arches paper with watercolors, colored pencil and markets, her paintings show glorious color-drenched sunsets behind the grit of the city. Ramirez paints from photograph studies and does not edit out power lines, poles and buildings.

“I look at it as authenticity,” she said. “Because I live in Spenard, there are usually a lot of buildings. I don’t let that stop me. … Most people will go ‘It’s ugly,’ but it’s not ugly.”

Ramirez uses a variety of media to illustrate her vivid sunsets. Working with crayon, alcohol based markers and colored pencil, the harder media goes on the bottom and allows her to layer material.

“It’s kind of like waxing skis,” said Ramirez, who works at Rei Co-op in Anchorage. “You want the hard stuff on the bottom.”

Some of the more irreverent art in the show comes from artist Duke Russell and Homer experimental filmmaker Michael Walsh. Russell’s series of paintings about nine Alaska myths evokes the 1980s Alaska postcards of Tom Sadowski and Jimmie Froelich, which depicted scenes like “Sunshine terrorizes Southeast Alaska residents” or “Beautiful Bethel beaches.”

Each Russell painting includes the phrase “Myth,” with some assertion like “We all live in igloos,” followed by “Actually,” and the truth, like “Everyone lives together in one big igloo townhouse with heated driveways.” For that myth, Russell has painted the giant igloo on the Parks Highway — a bit of an Alaska in-joke.

“It’s about Alaskans, Alaska, but not spruce, goose and moose,” Russell said.

Russell, who also lives in Spenard, said he painted his series to counter the Lower 48 impression of Alaska’s “ghastly reputation for nut buckets,” he said. It’s not.

“I’m surrounded by intellectuals,” Russell said.

Homer has that same quality, he said.

“Essentially, it’s the Austin (Texas) of Alaska,” he said of Homer.

Walsh, who seems to have a ready supply of rusty 55-gallon drums he uses in his art, made two looping films with sound that are projected in the inside of two drums. One film shows scenes of salmon fishing in Bristol Bay. Another includes clips of Alaska reality TV shows. As a filmmaker, Walsh sees an irony in tax incentives for films shot in Alaska being used by reality TV series. He noted there are 14 reality TV shows now set in Alaska or about Alaska.

“It’s really kind of sleazy, reality TV — how reality TV is in love with Alaska,” he said in his artist’s talk. “I think it’s kind of hokey and I don’t buy into it.”

Like fish, timber and minerals, “Reality is a natural resource in Alaska,” Walsh said.

“Or unnatural,” someone shouted from the audience.

It’s that attitude that defines “Unalaskana,” and drives the theme. Reality is not a resource to be shared only by those with a popular perspective, but those who examine it from unusual and ironic stances.

Michael Armstrong can be reached at michael.armstrong@homernews.com.