Two important events—one strategic, the other tragic—occurred in the Homer area on Sept. 21, 1928. Although they happened about a half-dozen miles apart, they were connected. Their combined effect had historic ramifications for the small community on the north shore of Kachemak Bay.

Just a few scattered buildings comprised Homer in 1928, but dozens of people did live there and die there. Dying was the problem. Homer, at that time, had no designated burial site. Consequently, residents were forced to adapt. They found other means to care for and honor their dead.

When Rose Perry died in Homer in March 1921, poor weather made it impractical to transport her body to Seldovia for interment in that community’s cemetery. Her husband, Capt. Thomas Perry, and some local folks concocted an alternative: burial on the north side of Kachemak Bay, in a site, according to an article in the Anchorage Daily Times, “of natural beauty … overlooking the blue waters of the bay and lofty pinnacles of the Kenai mountains beyond.”

The news account never specified the location, nor did it elaborate on how often such funereal adaptations occurred. But they did happen.

The story of Australian-born Roland Lee, in Diana Tillion’s “Pioneers of Homer,” ended similarly. In 1923, he began living in a series of small cabins on what became his 52-acre homestead near the mouth of Fritz Creek, east of Homer. When he neared death some years later, he “asked his neighbors to bury him in a shallow grave and seed it with flowers so they would be nourished by his remains.” His neighbors complied.

According to local lore, recounted in a 2013 Homer News article, a World War I veteran who died in the Old Town area of Homer was buried near his cabin, which later became the site of the visitor center for the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge. Longtime resident Steve Walli said that when the center was being constructed, he worried that someone would discover the remains.

When Walter R. Bell, who had come to Homer to homestead in 1916, was found dead on his doorstep shortly after celebrating the Fourth of July in 1921, friends tucked him neatly into the soil of his own garden. Today, his fenced-in grave lies just off the lower end of the Reber Trail, named for Bell’s daughter, who donated to the city the land through which the trail ascends.

But scattered local burials weren’t the only option.

When 73-year-old Homer fox farmer Joseph R. Lee died in June 1925 in an Anchorage hospital, his children back in Minnesota were cabled for instructions concerning what to do with the remains. Lee’s body, meanwhile, was taken to the Anchorage Funeral Parlor, and he was later interred in that city’s memorial park.

For the survivors and friends of most Homer residents who died in those early days, the post-mortem alternatives were limited: find a place in the area for a private interment, transport the body to Seldovia or some other locality with a cemetery, or send the body back to the state or country from which the deceased had originated.

By September 1928, a small group of concerned Homer residents had decided it was time to rectify what they considered a problem. It was time, they believed, for Homer to have its own burial ground.

A local trio—Mae Harrington, Alfred Anderson and Andrew Sholin—had done some homework. Government maps of the area showed that just east of town lay Section 16, public land that had been surveyed and set apart for the construction and maintenance of public schools. That designation was important because it prohibited homesteading, meaning that the institution of private property could never hinder their plans.

Or so they thought.

At the southwest corner of Section 16 (Township 6 South, Range 13 West, of the Seward Meridian), the three residents met and located a cemetery site “to be used by the Community of Homer, Alaska,” according to a 1959 affidavit by Harrington.

What happened several miles away that evening confirmed the belief of Harrington and the others that the creation of a Homer cemetery had been a necessity.

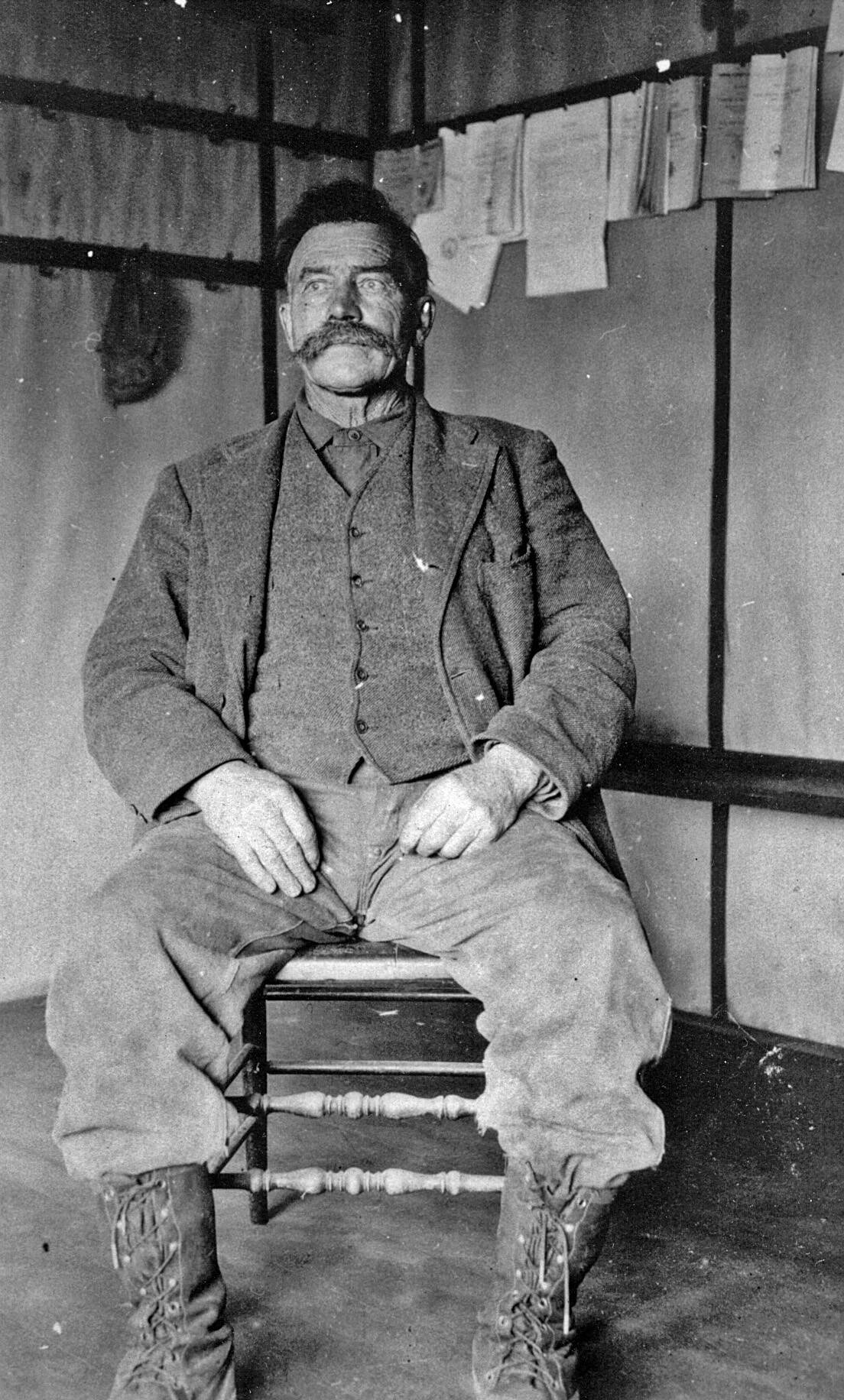

Up on Ohlson Mountain—an area now home to farmers and skiing enthusiasts—another trio was also hard at work. Thomas Olsen, Frank Soderberg and Karl “Chukin” Albertson had hiked in to a remote cabin they were using as a base camp. Just before dusk, they were out prowling in search of moose or black bear meat with which to fill their larders.

Newspaper descriptions of what happened next are sometimes contradictory, but the result was the same. It appears that Olsen and Albertson were tracking an animal at which they had both shot but which neither had hit. Their prey had descended into a ravine, and the two men had split up to cover a broader area. When Olsen spotted what he thought was the animal, he raised his rifle and fired.

What he hit was Albertson, wearing a backpack. The bullet went through one of Albertson’s arms above the elbow, snapping bone before lodging inside Albertson’s torso.

With night falling, Soderberg, who had been nearby, raced for help in Homer, as the grief-stricken Olsen did what he could to keep his friend comfortable, warm and dry.

Albertson died from blood loss at about 5 a.m. A group of Homer neighbors helped haul the body back to Homer, where a coroner’s inquest exonerated Olsen.

Two days later, at 11 a.m., Karl Albertson, a Norway native about 37 years of age, was laid to rest in Homer’s brand-new cemetery, thereby becoming its first occupant.

Shortly after he was interred, a group of Homer residents decided to make the cemetery official. Mae Harrington’s husband, “C.W.,” who was a mining engineer and surveyor, accompanied by fox-farming brothers Edward and Andrew Sholin, Alfred Anderson and some other, unnamed individuals, surveyed and placed stakes on the corners of a cemetery lot.

At this time, said Harrington, the lot was approximately two acres in size.

They sent a notice concerning their actions to the Land Office, and they kept a copy of that notice with the files for the local school. Their reserved copy was later lost in a fire—perhaps an omen for the troubles that the locals would later have in keeping their new cemetery.

TO BE CONTINUED