Anyone pondering if it’s ever too late to write a book can look to Sylvester David Kiyonuk “Sandy” Mazen Jr. for inspiration — and an answer. At age 90, in January the Homer writer published his first book, “Kiyonuk: An Arctic Alaska Boyhood” (Hardscratch Press, 2019).

Part memoir and part history, “Kiyonuk” is exactly the kind of book a seasoned citizen should write, for it tells not just the story of a boy born in Teller in 1928, but that of the Alaska he lived in as it went through dramatic changes from a territory to a self-sufficient state. If a Hollywood screenwriter wanted a central character to craft a sweeping Arctic epic around, Mazen would be your man.

Next week at 6 p.m. Thursday, June 20, Mazen, now 91, will read from and discusses “Kiyonuk” at the Homer Public Library. He holds another talk and reading from 3-5 p.m. on June 27 at the Anchor Point Library, and at 6 p.m. on Aug. 29 at the Carrie M. McLain Memorial Museum in Nome.

Mazen started his book a few years ago when a friend, David Ziegler, said Mazen needed a project and that writing a memoir might be a good idea. Much of the family story came from carbon copies of letters Mazen’s mother, Gertrude Kolkman Mazen, typed to Lower 48 friends after the family moved to Alaska in 1926. Mazen’s older sister, Constance Mazen Benston, wrote her own book based on those letters, “Mother’s Diary of Alaska,” published in 2003.

“The rest is my own personal memories as a kid growing up,” Mazen said.

Mazen’s wife, retired Homer News reporter McKibben Jackinsky, also helped in the project.

“She would ask some leading questions that would trigger old memories,” Mazen said. “I’m a very visual person.”

Mazen’s father, Sylvester David Mazen Sr., had been a World War I veteran who after the war went to Washington State Normal School, a teaching college in Ellensburg. The family came to Alaska when Mazen Sr. got a job at a school in Selawik, an Inupiaq village east of Kotzebue. He later got transferred to another teaching post in Cape Prince of Wales at the western tip of the Seward Peninsula.

It was there that Sandy Mazen came into the world. Since Wales didn’t have a hospital, his mother went to Teller in advance of his birth, delivering him at the Teller Mission Hospital. He got the name “Kiyonuk” from the Inupiaq word — now spelled “Qayuanaq” — that means “like sand,” given to him because his hair was the color of sand.

“It honors my birth state and what it means to be Alaskan born and raised,” Mazen writes.

Those early chapters of the Mazen family history before Sandy was born show how he fills in the blanks outside his own memory and experience. Many family photos got lost in a fire when the family lived in Oregon, so Mazen supplements that record with historical photographs of the time period.

With the help of Jackinsky and Hardscratch Press editor and publisher Jackie Pels, Mazen has thoroughly documented the memoir. “Kiyonuk” also includes excerpts from family journals, scholarly articles and newspaper clippings. Each chapter includes notes for citations, and the appendix has a thorough bibliography and index.

“Kiyonuk” eases into Mazen’s voice with the third chapter, when the Mazens move to Shaktoolik to live a subsistence lifestyle. His earliest memories come from that time, and the book builds on those memories. Mazen doesn’t gloss over his childhood and teenage mischief, and writes honestly of a stern but loving upbringing.

The book also gives insight into historical moments as seen by the young man who lived through them. After Shaktoolik the Mazens moved to Nome. They endured the real danger of Japanese attack after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. Like other Alaska children, he also spent part of the war with relatives in Washington.

He also saw racism against Alaska Natives in Nome. In 1944, 15-year-old Alberta Schenk, whose father was white and whose mother was Inupiaq, got fired from her job at Nome’s movie theater because she complained about a policy that made Natives sit in the balcony. She later went to the theater with a white soldier, and sat in the whites only area. When she refused to leave, she got arrested. A telegram she sent to Territorial Governor Ernest Gruening about the incident prompted him to support and the Alaska Legislature later to pass the Alaska Anti-Discrimination Act.

Mazen writes that his father spoke loudly against the theater’s policy: “‘Unchristian behavior,’ that was something he said.”

The memoir also tells another story, that of an Alaskan who leaves to live and work Outside, only to return. Mazen’s story continues through his adult years working as a teacher, guidance counselor, college professor and psychologist in Arizona and Washington. Eventually he came back to Alaska, settling in Homer in 1998 to be closer to his daughter, Tina Seaton, and her family.

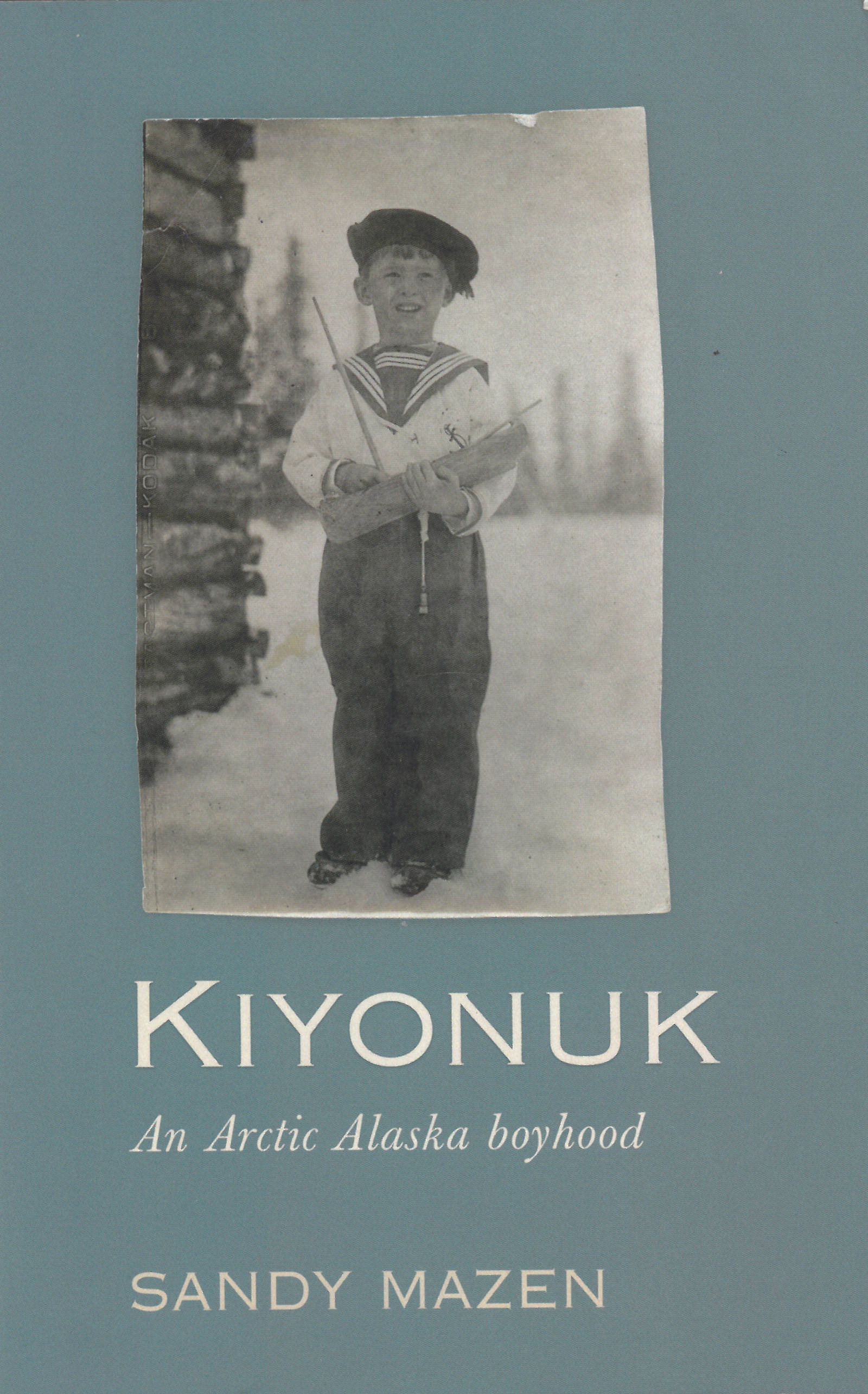

Later in life Mazen became a mariner and sailor, teaching boating safety for the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary and also serving as commodore of the auxiliary. At an early age he writes of how his mother must have sensed his fascination for the sea. The cover photo shows him in a sailor suit his mother made for his fourth birthday and holding a wooden sailboat his Shaktoolik godfather made him.

It shouldn’t be a surprise if there’s also a boat on the cover of Mazen’s next book. He said his next book will be about his sailing adventures and work with the Coast Guard auxiliary.

Reach Michael Armstrong at marmstrong@homernews.com. Mazen’s wife, McKibben Jackinsky is a freelance writer for the Homer News.