Whoever coined the saying about real life being stranger than fiction may have had the town of McCarthy, Alaska, in mind.

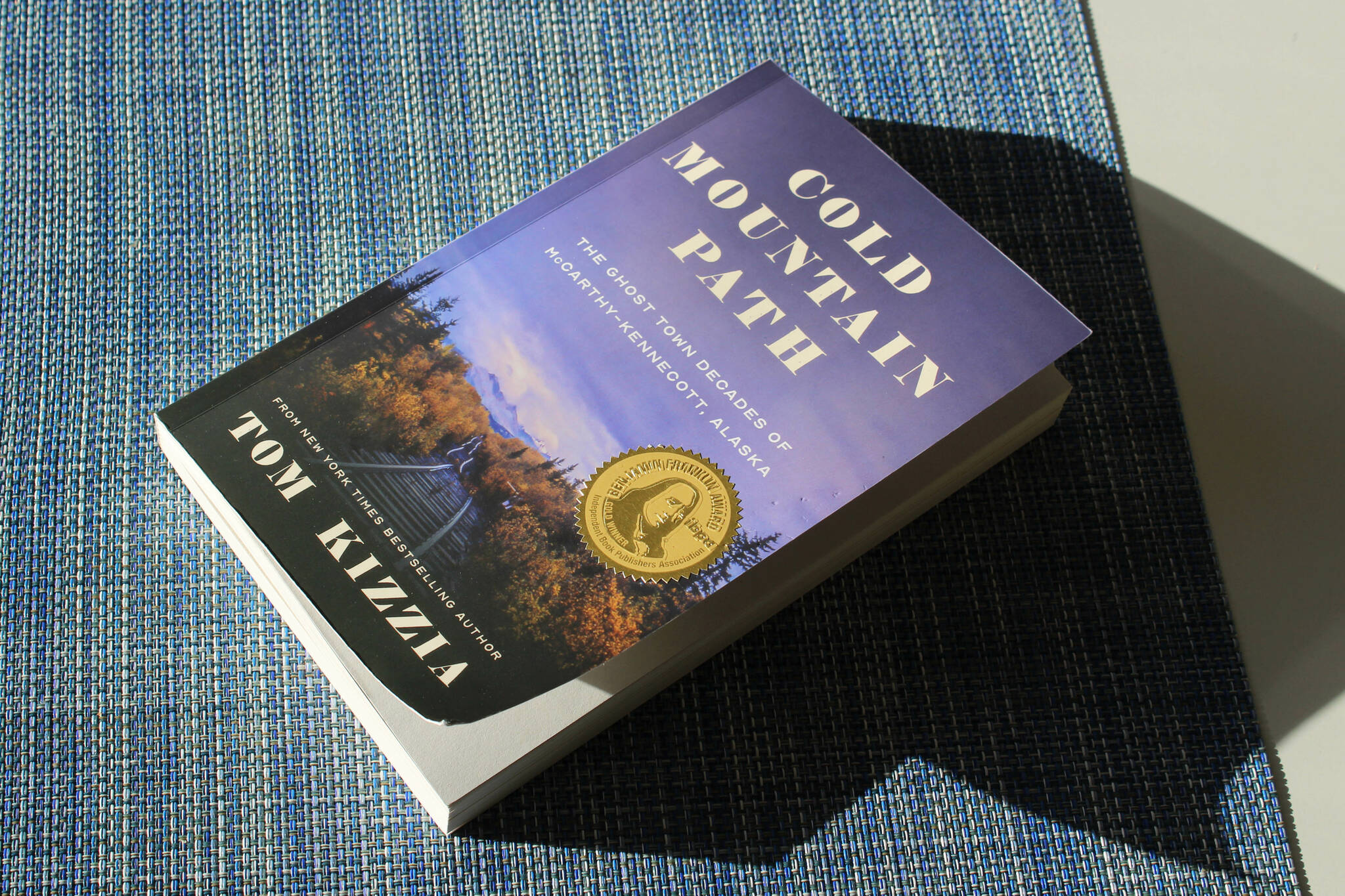

That was my opinion several chapters into Tom Kizzia’s “Cold Mountain Path: The Ghost Town Decades of McCarthy-Kennecott, Alaska,” which I bought recently in the Anchorage airport. I haven’t read Kizzia’s 2013 true crime book “Pilgrim’s Wilderness: A True Story of Faith and Madness on the Alaska Frontier,” for which he is perhaps better known.

When it comes to the mining history of McCarthy, I was largely going in blind as I read the first pages of “Cold Mountain Path.” Courtesy of Erin McKinstry’s podcast “Out Here,” which chronicles her life in and the history of McCarthy, I was familiar broadly with the fact the town was in the middle of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, that it had once been a bustling mining hub and that a shooting had changed the fabric of the community.

In the introduction to “Cold Mountain Path,” Kizzia describes the pages that follow as “the lost chapters” from “Pilgrim’s Wilderness” that chronicle McCarthy’s ghost years leading up to a 1983 shooting that left six dead. It was in 1983, Kizzia writes, that he first visited McCarthy, on assigned with the Anchorage Daily News, which had dispatched him to write about the shootings.

“Like most people who had lived in the north for any amount of time, I’d heard of McCarthy,” Kizzia writes in the book’s prologue. “It was a boomtown back in a picture book era of copper mines and ore trains, abandoned now — but not entirely.”

In “Cold Mountain Path,” Kizzia assembles all the necessary elements for a compelling story — colorful characters, a unique setting and conflict galore. It opens with the dramatic imagery of the last mining trains pulling out of town, introduces a diverse cast of residents and gives a comprehensive account of the rise and fall of the Kennecott copper mine.

There’s a recognizably Alaska tenor to the way Kizzia writes about McCarthy’s inhabitants, both current and past. Familiar themes include man versus nature, old versus new and progress versus preservation.

One chapter charts the journey of the elusive “Raven,” a man thought to be a drug dealer and who was believed to have pillaged the local cemetery for skulls to use as candle holders. Another recounts a visit by singer John Denver, whose “Wrangell Mountain Song” depicts a rosier McCarthy than Denver himself apparently experienced.

No matter how outlandish a story may seem though, readers can rest assured that Kizzia has done his research; more than 25 pages of notes appended to the text reference such primary documents as the 1938 “Alaska Mines Annual Report,” Ethel LeCount’s journal, Kizzia’s personal interviews and environmental impact statements. The sources are varied and meticulously documented.

I visited the Alaska State Museum last weekend and, standing before a display about Alaska’s mining history that included a black and white image of the Kennecott mine and a wall of equipment artifacts, I found myself projecting on to the exhibit stories from “Cold Mountain Path.”

A display chunk of copper had me running through Kizzia’s tale of the McCarthy “ghost mansion,” which was built by a copper tycoon and once adorned with an entirely copper fireplace. It occurred to me then that Kizzia succeeded in what I think all history writers aim for, which is to make the past feel alive. That’s certainly what “Cold Mountain Path” did for me.

“Cold Mountain Path” received two Independent Book Publishers Association Ben Franklin Awards, including the Bill Fisher Award for Best First Book: Nonfiction and silver for Regional. It was published in 2021 by the McCarthy-based Porphyry Press.

Reach reporter Ashlyn O’Hara at ashlyn.ohara@peninsulaclarion.com.

Off the Shelf is a bimonthly literature column written by the staff of the Peninsula Clarion.