AUTHOR’S NOTE: Cooper Landing, on the Kenai Peninsula, was once identified with a postal inspector named Charles Arthur Riddiford. In fact, residents of the landing named their first post office and their first school after Riddiford, a man who never lived in Alaska. This is the story of how that naming likely came to be.

Charles Riddiford’s 1917 visit to Alaska, in his capacity as chief inspector for the Northwest Division of the U.S. Postal Service, was a quiet affair compared to his second and third trips to the Territory.

Two announcements connected to that first visit appeared in the Iditarod Pioneer newspaper later that year. In June, Riddiford issued a circular to the Iditarod postmaster, advising him and all Alaskans to refrain from the “misappropriation of United States mail bags and sacks for private use.” Riddiford claimed that mail bags had been “frequently found in prospectors’ cabins and at camps, and in some instances … (had been) cut up for other use.”

Riddiford reminded postmasters and the general public that fines and/or jail time could result from the misuse of property belonging to the USPS.

In December, the Iditarod Pioneer reported the arrest of the Eagle postmaster, who had been charged with embezzling postal funds. Inspectors had arrived unannounced at Eagle late one night and launched an immediate inspection of the post office records, quickly determining that the postmaster’s accounts were short by $6,000.

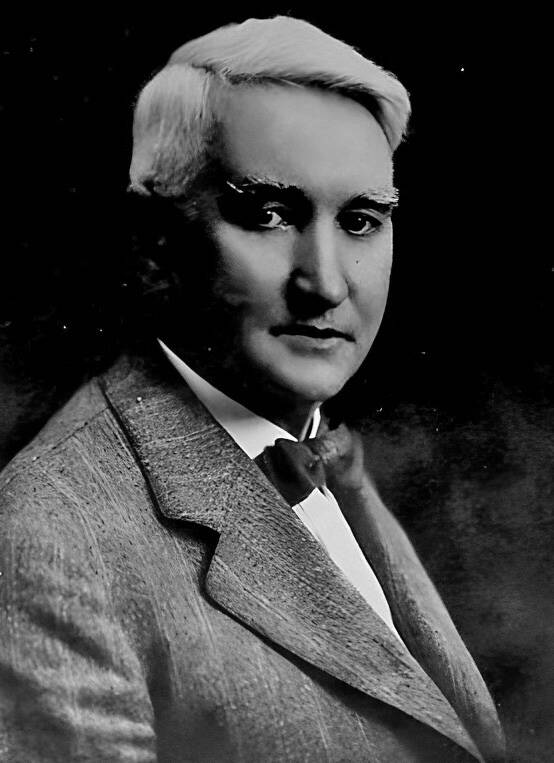

Generally speaking, Charles Riddiford did not seem to be an imposing figure. His 1920 passport application listed him as standing just over 5-foot-5. He was described as having a high forehead, a “regular” mouth and a round chin, with a ruddy complexion, gray hair and blue eyes. His passport photo showed an older-looking man — Riddiford was 53 — who appeared dapper and distinguished in a dark suit, white shirt and dark bowtie.

But make no mistake: Riddiford’s mild looks were deceiving. Defense attorneys had referred to him as “that white-haired, wire-haired terrier” and “that gray-haired, sly old fox.” In obituaries, he was called the “dreaded inquisitor of the Pacific northwest” and the “nemesis of violators of the postal laws.”

The biggest case in his career — the investigation that launched him into nationwide acclaim — began in 1923, one year before his second visit to Alaska and two years before his first complete tour of the Territory’s postal system.

The 1923 crime is said to have “shocked the nation” and precipitated a three-and-a half-year, worldwide manhunt for its three perpetrators (19-year-old Hugh DeAutremont and his older twin brothers Roy and Ray). The DeAutremonts had held up a passenger train as it passed through a tunnel in the Siskiyou Mountains of southern Oregon. Once they got the train stopped, they dynamited its mail car, killing a mail clerk in the process, and shot three trainmen to death.

Despite all this mayhem, they got no money for their troubles because the dynamite had ignited a fire so intense that they found it impossible to enter the mail car. Empty-handed, they fled for their lives. Riddiford and other law enforcement officials were almost immediately in pursuit. Within a week or so, they had discovered the bandits’ identities. They issued a substantial reward and eventually sent out 2.4 million wanted posters in eight languages around the world.

In 1927, a soldier returning from duty in the Philippines saw one of the posters and recognized fellow soldier James C. Price as Hugh DeAutremont. Authorities arrested DeAutremont in Manila and brought him to trial in Oregon. The ensuing publicity prompted more attention to the posters, and the twins were soon identified as factory workers Clarence and Elmer Goodwin in Steubenville, Ohio. By July 1927, all three had confessed and been sentenced to life in prison.

Hugh was paroled in 1958 but died a few months later of stomach cancer. Roy was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1949, was transferred to Oregon State Hospital where he received a frontal lobotomy; he died in a nursing home in 1983. Ray was released from prison in 1961, and the governor of Oregon commuted his sentence in 1972. All of them, however, outlived the man who helped bring them to justice.

In 2023, the USPS recalled the centennial of the crime and described the investigation as “one of the largest and most expensive manhunts in U.S. history.”

Connection to the North

It was directly upon the heels of that crime that Riddiford made his second trip to Alaska. On July 5, 1924, the Seward Daily Gateway reported, “C. Riddiford, who has been in Anchorage for some time, left for Cordova on one of the last boats, presumably in connection with the recent post office robbery there.”

During this same year, the Riddiford Post Office, at Cooper’s Landing, opened its doors, with Frances I. Brown as postmaster.

It isn’t difficult to imagine that offering to name a brand-new post office in a tiny, upstart community after someone famous and influential within the U.S. Postal Service might be perceived as lending legitimacy to the request.

This notion may have seemed particularly apt in 1925 when the U.S. Postmaster General ordered Riddiford and his team to return to Alaska and make a survey of all its 168 post offices. The Alaska tour began in mid-June, concluded in mid-August, and attracted the attention of the Alaska Daily Empire (Juneau) and the Anchorage Daily Times.

Riddiford told the press that they had inspected 155 of the Territory’s post offices but had been unable to reach the remaining 13, all of which were located in western and northern Alaska. He said that the weather in the Bering Sea had been so bad in July that his vessel had been forced to hole up for 10 days near Teller, just north of Nome, before retreating.

Back at Cooper’s Landing, meanwhile, with a post office name in place and residents receiving letters and packages addressed to Riddiford, it made further sense for the community’s first school to follow suit. Consequently, when the Riddiford School opened in 1929 — with Margaret “Peggy” Barnett as the teacher — the place where children went for an education was connected directly to the place where adults had been going to pick up their mail.

The problem for residents who favored the Riddiford name was two-fold: Many people in the area refused to shed their “Cooper’s Landing” identity. In fact, some said that the Riddiford post office and school were at Cooper’s Landing.

Also, although Charles Riddiford continued his stellar career, his star never burned brighter than during the DeAutremont case, which concluded two years before the Riddiford School opened its doors. The Riddiford Post Office had closed in 1928, but that fact didn’t keep the school from adopting the Riddiford name.

However, by the time low enrollment forced the closure of the Riddiford School in late 1935, Riddiford the man had been dead for four years.

Charles Arthur Riddiford had taken ill in early December 1930. He was suffering from chronic appendicitis, an enlarged prostate and kidney problems. After surgery on Jan. 19, 1931, he died the next day of a pulmonary embolism at the Swedish Hospital in Seattle. He was 63 years old.

Assistant Spokane postmaster Frank P. Hicks said, “I grew up in the post office service here with Charles Riddiford. He was held in high esteem by all of us. He was an unusually keen man, as his record for catching crooks will show.”

Fellow postal inspector Arthur A. Paisley added: “The men of his division considered him as the best ‘inspector in charge’ in the entire service.”

When the Cooper Landing School opened in 1952, the Cooper Landing Post Office had been back in business for five years, and the connection to Charles Riddiford continued to fade with time.