AUTHOR’S NOTE: This is the first of a series of articles concerning places and landmarks on the Kenai Peninsula that once bore different names. Much of today’s article appeared previously in an article of mine in the Redoubt Reporter in 2010.

Every year, thousands of travelers stop at Tern Lake, at the junction of the Seward and Sterling highways, to gawk at terns or swans, to photograph waterfowl, to capture the reflection of the surrounding mountains, or simply to stand in awe of this freshwater jewel glistening in the summer sun.

Most of these visitors to the lake are, however, blithely unaware that it was little more than a marsh before the mid-1940s, and that, several decades ago, it was not named Tern Lake.

In the late 1940s, as a tour bus driver for Malcolm Bus Line, Willard Dunham used to haul passengers (for $10 each) from the steamships docking in Seward’s harbor up the rough new Seward Highway. One of his regular stops along the way was what was then called Mud Lake because it was—despite its attraction to terns even then—little more than a spongy bog.

In fact, a 1915 reconnaissance map of the area depicts no body of water there at all.

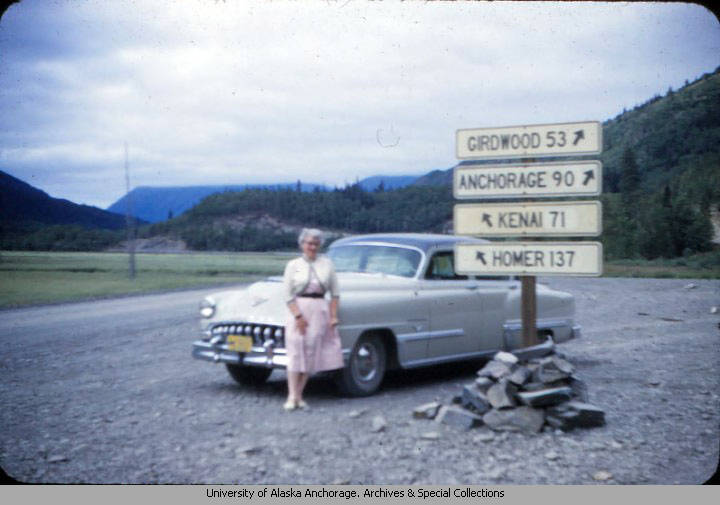

Today, Tern Lake sits at a confluence of asphalt ribbons and alpine valleys. From this point, travelers can motor to Seward, Anchorage or Soldotna and Kenai and points beyond. The lake—fed largely by snow melt from its alpine surroundings, chiefly Wrong Mountain, just east of Crescent Lake—is drained by the narrow, meandering waters of Daves Creek. The creek parallels the Sterling Highway west until it dumps into Quartz Creek and continues, united, toward Sunrise Inn on lower Kenai Lake.

Daves Creek and Tern Lake form high-quality spawning and rearing habitat for chinook, coho and sockeye salmon, and for rainbow trout, Dolly Varden, slimy sculpin and round whitefish. These fish in their various stages attract predators such as the terns, while the flora in the lake and along its perimeter attract browsing moose and feeding, dam-building beavers.

Even back in Dunham’s day, the lake was an attraction because the terns were so plentiful. “I’d stop at Mud Lake and let [the tourists] watch the terns—feeding, chasing ducks, and nesting,” Dunham said in 2010. “And the terns were always there. Loads of ’em, and they were great to watch.”

Dunham, who arrived in Seward as a teen-ager in 1943, drove one of three 1937 buses that his boss, Harold Malcolm, had purchased from Washington State Transit and had shipped north to Seward. Up and down the graveled highway, Dunham carried 27 passengers at a time into the Cooper Landing area.

Each 110-mile round-trip took almost eight hours to complete, including sight-seeing stops, and Dunham made this trip twice a week, every Tuesday and Thursday throughout the summer months of 1948, 1949 and 1950.

“We used to pick up the passengers and sell trips to what was called Henton’s Lodge at that time—where they cross on the ferry and the combat fishing is now,” Dunham said. “That was the end of my trip.”

Along the way, Dunham would stop in Moose Pass or near Crescent Creek to see if any miners were on hand to perform a demonstration, spin a few yarns, and provide a spiel for the tourists. He would also halt at Lawing to show them Alaska Nellie’s place, and pull in for a few minutes at Our Point of View above Kenai Lake.

Dunham also fed his patrons—usually a cold beef sandwich, some chips and hot coffee at Henton’s—before turning back toward Seward. It was a good gig, he said, until a few tour-bus competitors arrived in Seward and siphoned off some of his business.

Of course, Dunham said, tourists weren’t the only ones who enjoyed the Mud Lake area. It was fairly easy to circumnavigate the lake on foot in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and he was among a number of men who packed their shotguns around the perimeter to reach the abundant waterfowl.

“I used to do a lot of duck hunting in there,” Dunham said. “It was a great fall place because the flocks came up through the canyon there. When the weather was bad or socked in on either side, they would land in Mud Lake because it was a great place to feed.”

Over time, the Tern Lake basin has continued to fill, and some topographic maps now show it to be nearly three-quarters of a mile long in places. Because it is dotted with tiny mossy islands, it can be difficult to fully appreciate its size when standing at lake level.

Although the Daves Creek outlet was altered when the Sterling Highway was constructed in the late 1940s, and changed somewhat again when the highway was realigned in the 1960s, Dunham believed those changes didn’t fully account for the lake’s growth. He did, however, believe that a combination of nearby roadbeds and building construction may have altered the water table.

He also thought that melting pockets of glacier ice in the surrounding mountains helped to gradually fill the Tern Lake basin.

According to Cooper Landing historian Mona Painter, the “driving force” in changing the name of the lake from Mud to Tern was a Seward resident named Luella McMullen James, who owned an apparel store named McMullen’s on Fourth Avenue in Seward. James also owned a summer cabin on lower Kenai Lake, and she didn’t think Tern Lake’s original name properly suited its beauty.

The change became official sometime in the 1960s.

End note

It must be acknowledged that many, if not most, of the places and landmarks discussed in this series of articles once bore Native names. Some of those names have persisted in one form or another—often Anglicized or Russified or otherwise transformed into the languages of the mapmakers, thus achieving the perception of permanence by moving to print what had once been part of a long oral tradition.

In the case of Mud Lake, we have no specific Dena’ina name for the body of water—perhaps because of its historic appearance as little more than a swamp—but we do have something close. In Peter Kalifornsky’s 1991 collection of writings, A Dena’ina Legacy: K’tl’egh’I Sukdu, he offers a list of Dena’ina place names (toponyms) for common locations on the Kenai Peninsula.

For the area he calls “canyon in Moose Pass area near highway turn-off,” he presents the Dena’ina name Tl’egh Qilant, which translates to “sedge place.”