AUTHOR’S NOTE: Lawrence and Lorna Keeler, along with their three children and Lawrence’s older brother Floyd, left Oregon on June 3, 1948, and began driving to what would become their new home on the southern Kenai Peninsula. By late June, Lawrence and Lorna were in Kenai, working in a cannery to earn enough money to afford transportation to the Anchor River.

Motivation

From the beginning, Lorna Keeler had been more eager than her husband Lawrence to move to Alaska. She made this clear years later in a historical writing and in conversations with her daughter Ina, the only one of her children to be born in Alaska.

“At Port Orford, Oregon, where we lived,” Lorna wrote, “I had the privilege to see movie pictures taken by friends who had worked at a mine in Alaska. They showed pictures of (the) Matanuska Valley and Anchorage. I got the ‘Alaska Bug’ and for seven years I talked ALASKA!

“I subscribed to a magazine called Alaska Life,” she continued. “After reading that for several years, it finally convinced Lawrence we should go to Alaska. By that time our kids (were) 14, 12 and 5 years old. The boys were so interested in hunting and fishing, and April was not far behind.”

“They’d’ve probably been up here 10 years sooner,” said Ina (Keeler) Jones, a longtime resident of upper Kachemak Bay. “Mom was the one with itchy feet wanting to move. Dad was kind of happy where they were at. But Mom said there was just getting to be too many cars on the road (back in Oregon) and too much drinking, and she didn’t want to raise her kids down there where there was so much crime. She wanted to move to Alaska and get away from it.”

Her mother never regretted her decision to move north, Ina said. “She loved every minute of it…. She was the typical pioneer woman.”

Ina’s older sister, April (Keeler) Williams, a longtime resident of Soldotna, agreed. “(Mom) was anxious to get up here,” she said. “She had relatives up here.”

Lorna had been born a Chenoweth, the same family as the mother of Lorna’s second-cousin, Larry Clendenen, who had already been living for a year with his wife Inez and their children in Anchor Point. Larry, who had visited the Keelers in Oregon in the spring of 1948 and inspired them with a description of life in Anchor Point, had filed for a homestead patent there in June 1947, the same month he and his family had arrived.

After a month of earning money by doing cannery work in Kenai, the Keelers sold their 1946 Willy’s jeep and two-wheeled, pull-behind trailer and made plans to complete their journey.

New Home

Lorna and Lawrence Keeler embarked on an exploratory trip to the Anchor River after leaving their two youngest children (son Marion and daughter April) with Lawrence’s niece, Myrtle, who had come a year earlier to the Kenai Peninsula with her husband, Melvin Minor, her father (Floyd Keeler) and two of her brothers.

With their older son Larry, Lorna and Lawrence chartered a flight with Harry White, who kept a bi-plane on floats anchored near a cannery at the mouth of the Kenai River.

White landed on the beach that morning near Laida Spit, where the mouth of Laida Creek (now Granroos Creek) lay just north of the mouth of the Anchor River. The Keelers got a good look at the bluff above the river mouth and noticed sawmill-quality stands of timber there. They liked the vistas and the possibilities and were convinced they had found their future home.

The Clendenens lived on the near side of Laida Creek. Across the stream was the homestead of an older man named John Paul “Jack” Standke, who lived with his mining and trapping partner, John Martin “Smitty” Smith.

Since Standke and Smith were preparing to leave the Anchor Point area, Lawrence and Lorna made arrangements to purchase Standke’s homestead. According to daughter April, they paid Standke $4,000.

Both the 58-year-old Standke and the 70-year-old Smith moved to Homer and were counted there in the 1950 U.S. Census. Standke eventually moved out of state and died in San Francisco in January 1954, but the Keelers had not seen the last of Smith.

On that first day at Anchor Point, however—since their pilot had simply dropped them off—the Keelers had to find alternate means of returning to Kenai. They began hiking north on the beach. Two of the many people they met on the way—sawmill operator Rex Hanks of Happy Valley and Nick Leman of Ninilchik—would become longtime friends.

A few miles past Ninilchik, some men working on a fish trap informed the Keelers that they could catch a ride back to Kenai on a fishing tender arriving later that the day.

On Aug. 3, 1948, Lawrence and Lorna made their official move from Kenai to Anchor Point aboard a vessel called the John Adams. There, since roads were few, they did a lot of walking and caught a lot of rides until the Sterling Highway had been completed.

In 1951, they bought a new jeep. By that time, they had already moved again.

Bigger Trees

Before their next move, the Keelers spent more than two years in Anchor Point. There, one of Lawrence and Lorna’s big concerns was continuing their children’s education.

“We had to send April to school at five years of age to make a total of eight children so the Territory would give us a teacher,” wrote Lorna. That teacher was Helen Smith, and school was held in a small cabin built of cottonwood logs on the Clark Peterson homestead. Desks and books had been donated by the school in Homer.

“Our three kids, plus the Hostetter boys, had to cross the Anchor River on a carriage suspended from a cable, or rope, which ran from bank to bank,” said Lorna. “At high tide, they had to climb the sides of the carriage to keep their feet dry.”

In about 1951, Lawrence, while working for the Alaska Road Commission, was on the lookout for more timber. Soon, he began eyeballing a piece of property near lower Stariski Creek, north of Anchor Point.

After selling their Anchor River homestead to Dr. Milo Fritz and his wife Elizabeth, the Keelers became Stariski residents. Their sons, now teen-agers, worked the sawmill there with Lawrence—except during fishing, moose-hunting and trapping seasons—and supplied logs and lumber for cabins and homes from Clam Gulch to Homer.

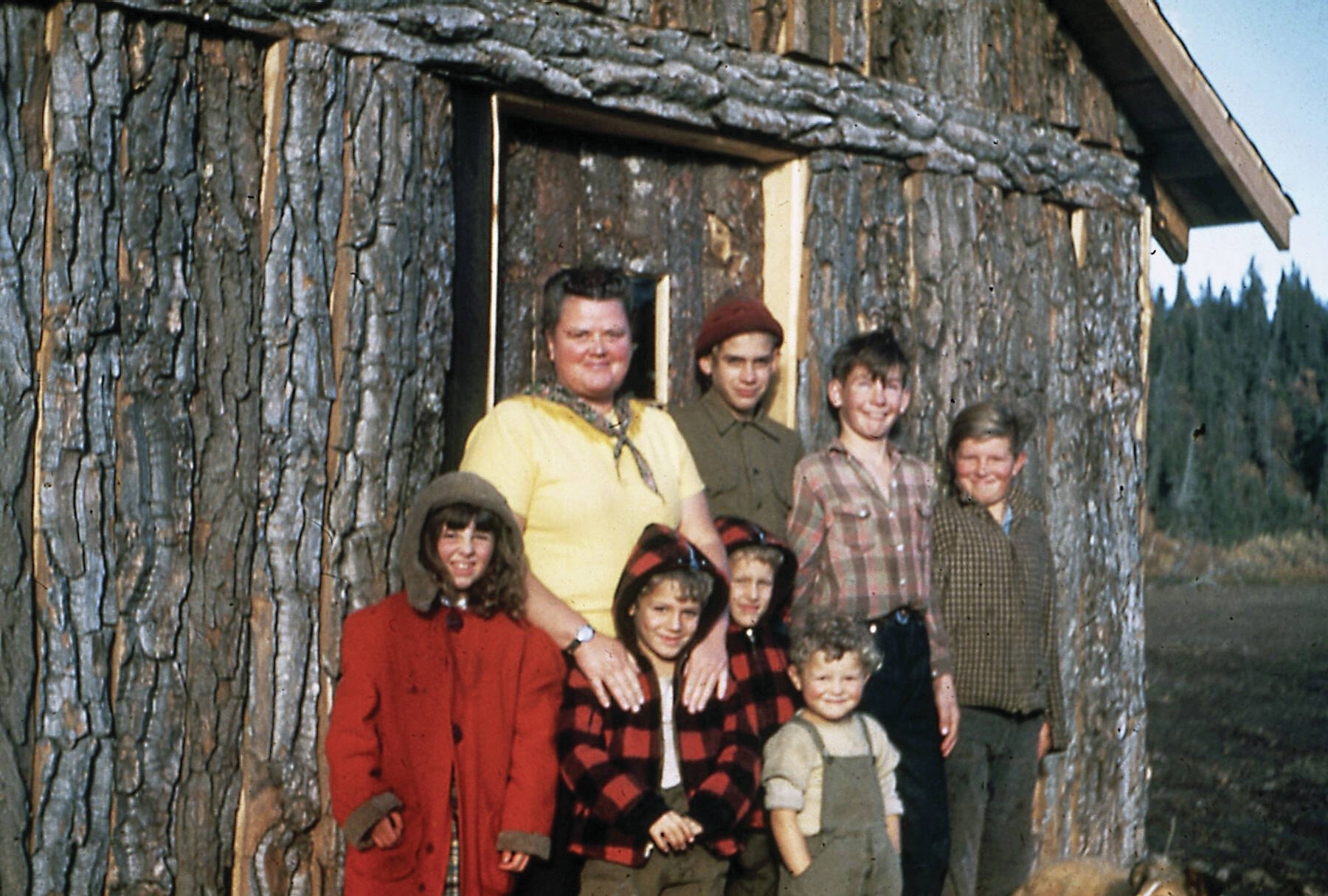

Throughout most of the 1950s, the Keelers lived near the creek and remained active socially. In 1955, 12 years after April, her youngest, had been born, Lorna gave birth to a second daughter. But Ina Lea’s arrival wasn’t the only surprise appearance in the Keeler household during this decade.

A few years earlier, “Smitty” had returned.